Part 2, Strategy 4

Action Item 1: Use programming and treatment that works to reduce recidivism.

Why it matters

State and local leaders need to ensure that they are investing wisely in quality programming and treatment. Providing people with the right combination of services isn’t enough to improve public safety or health outcomes; the services delivered must be high quality, research based, and tailored to each person’s needs. Far too often, behavioral health care providers do not have the necessary specialized knowledge and training on evidence-based practices to provide effective treatment to people in the criminal justice system. (For additional information on improving responses to people who have behavioral health needs, see Part 1, Strategy 2.)

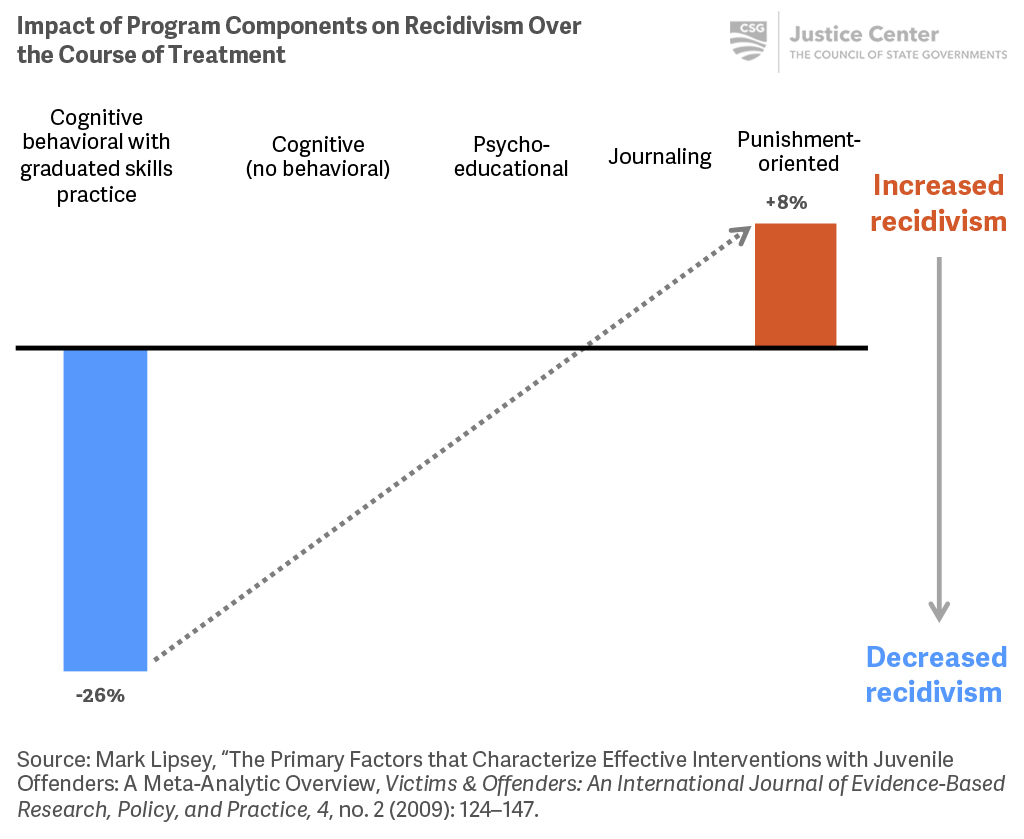

Poor quality programming not only wastes taxpayer dollars, it can increase recidivism. Research has shown that programs reduce recidivism most effectively when they are tailored to a person’s assessed risk of reoffending, address certain needs that contribute to criminal behavior, and utilize responsive strategies to change behavior.[34] Further, research has shown that programs using a cognitive behavioral approach that includes skills practice have a significant impact on reducing future criminal behavior.[36]

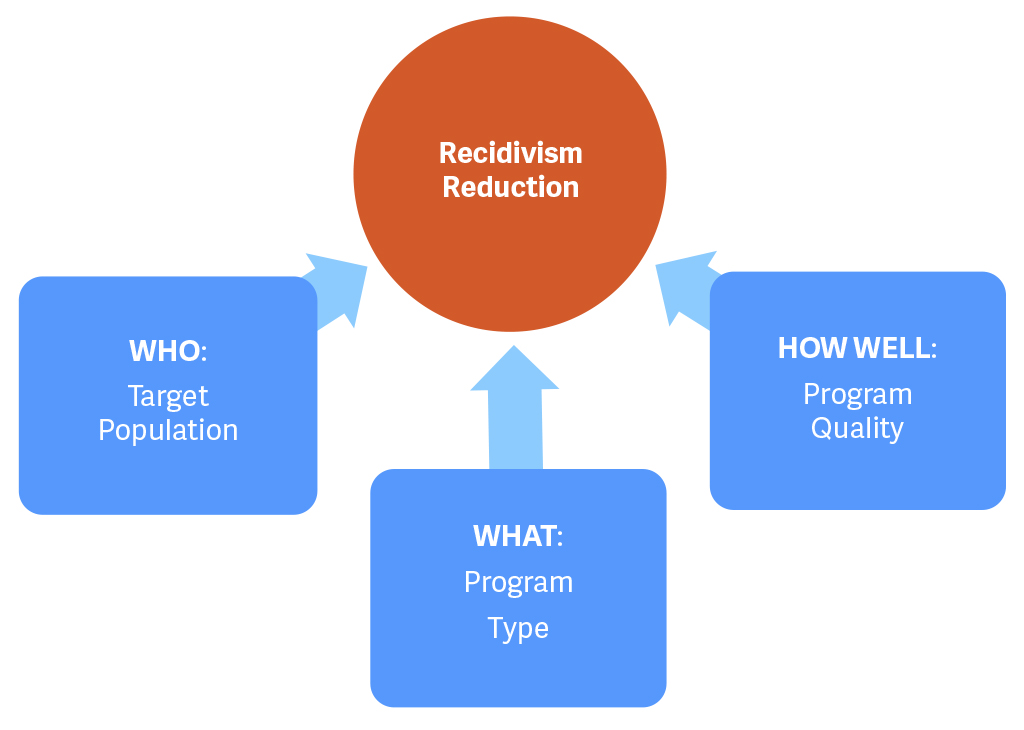

Programs that are effective at reducing recidivism have three core elements in common: (1) they target people who are most likely to reoffend (who); (2) they use practices rooted in the latest research on what works to reduce recidivism (what); and (3) they regularly review program quality and evaluate how closely the program adheres to its established model (how well). It isn’t enough for people on supervision to participate in programs based on models shown to reduce recidivism. Research has shown that the way in which programs are delivered is critical to improving outcomes; yet states typically devote little attention to establishing program quality assurance.[37]

What it looks like

- Assess the range of current treatment and programs and their capacity to address the needs of people who are incarcerated and on supervision.

- Prioritize programs for people who are most likely to reoffend and who have the greatest criminogenic needs.

- Require that programs use practices based on the latest research on what works to reduce recidivism.

- See Case Study: Iowa and Illinois prioritize use of effective programs

- Require quality assurance processes and include observations of program delivery as part of regular evaluations to assess program quality.

- Review how well programs are performing and publish results.

- See Case Study: States establish measures to improve quality of programs

- Eliminate ineffective and outdated programs.

- See Case Study: Idaho overhauls programs after in-depth assessment

Key questions to guide action

- What types of programs are provided to people who are incarcerated and on supervision? Are these programs prioritized for people who have the highest risk of reoffending? Are they based on the latest research on what works to reduce recidivism?

- Are there requirements to evaluate programs on a regular basis? When were these programs last evaluated?

- How might your state increase the performance of programs and treatment utilized by supervision agencies?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

To reduce recidivism, policymakers need to consider who receives programming, what types of programs are employed, and the quality and effectiveness of those programs.

Additional Resources

Key elements of effective programs

Research has demonstrated that the most effective recidivism-reduction programs adhere to risk-need-responsivity (RNR) principles and use a cognitive behavioral approach. In addition to targeting the most intensive supervision and services to people who are most likely to reoffend, programs should also focus on criminogenic needs, such as criminal thinking or attitude. Programs that focus only on non-criminogenic needs (dynamic factors that are not associated with recidivism), such as self-esteem or relationships, do little to lower recidivism.

Finally, programs should rely on methods that have been proven to be effective with people in the criminal justice system, such as cognitive behavioral programs, that help people who have committed crimes identify how their thinking patterns influence their feelings, which in turn influence their actions. Effective programs should be implemented in a way that promotes active participation and incorporates graduated skills practice (e.g., making accommodations for language or literacy issues). For additional information, see Three Core Elements of Programs that Reduce Recidivism: Who, What, and How Well.

Assessing program quality

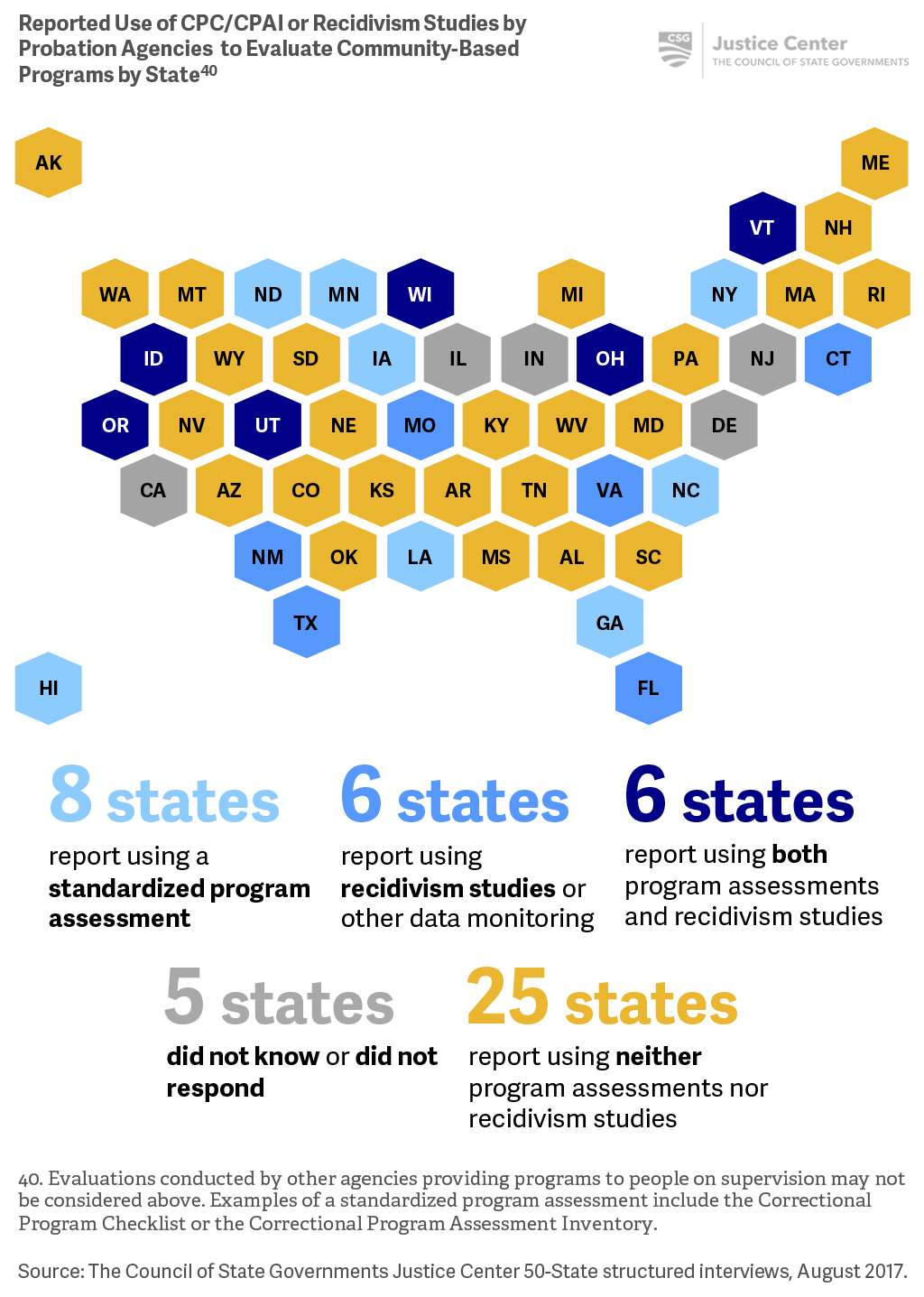

Many states don’t know if their programs target the right people or how well those programs are delivered. There are several resources to help states take stock of existing programs.

- The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center’s Justice Program Assessment (JPA) is an intensive, system-wide evaluation of an agency’s recidivism-reduction programs to determine whether the programs target people who are most likely to reoffend, whether they incorporate evidence-based practices, and how well they are performing. The JPA helps policymakers and agency leaders take stock of the quality and efficacy of their programs and determine whether their considerable investment in these programs is allocated in a way that maximizes the likelihood of reducing recidivism.

- Results First works with states to implement an innovative cost-benefit analysis approach that helps them invest in policies and programs that are proven to work.

- The Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR) Simulation Tool assists criminal justice and behavioral health agencies with integrating evidence-based practices into policy and practice in their jurisdictions.

Tools such as the Correctional Program Checklist and Correctional Program Assessment Inventory can help agencies evaluate the quality of programs and identify program components that are likely to reduce recidivism. Measuring recidivism and other key program outcomes helps ensure that programs are achieving their goals.

Cognitive-behavioral programs with graduated skills practice have the largest impact on reducing recidivism.

Additional Resources

Behavioral health screening and assessment

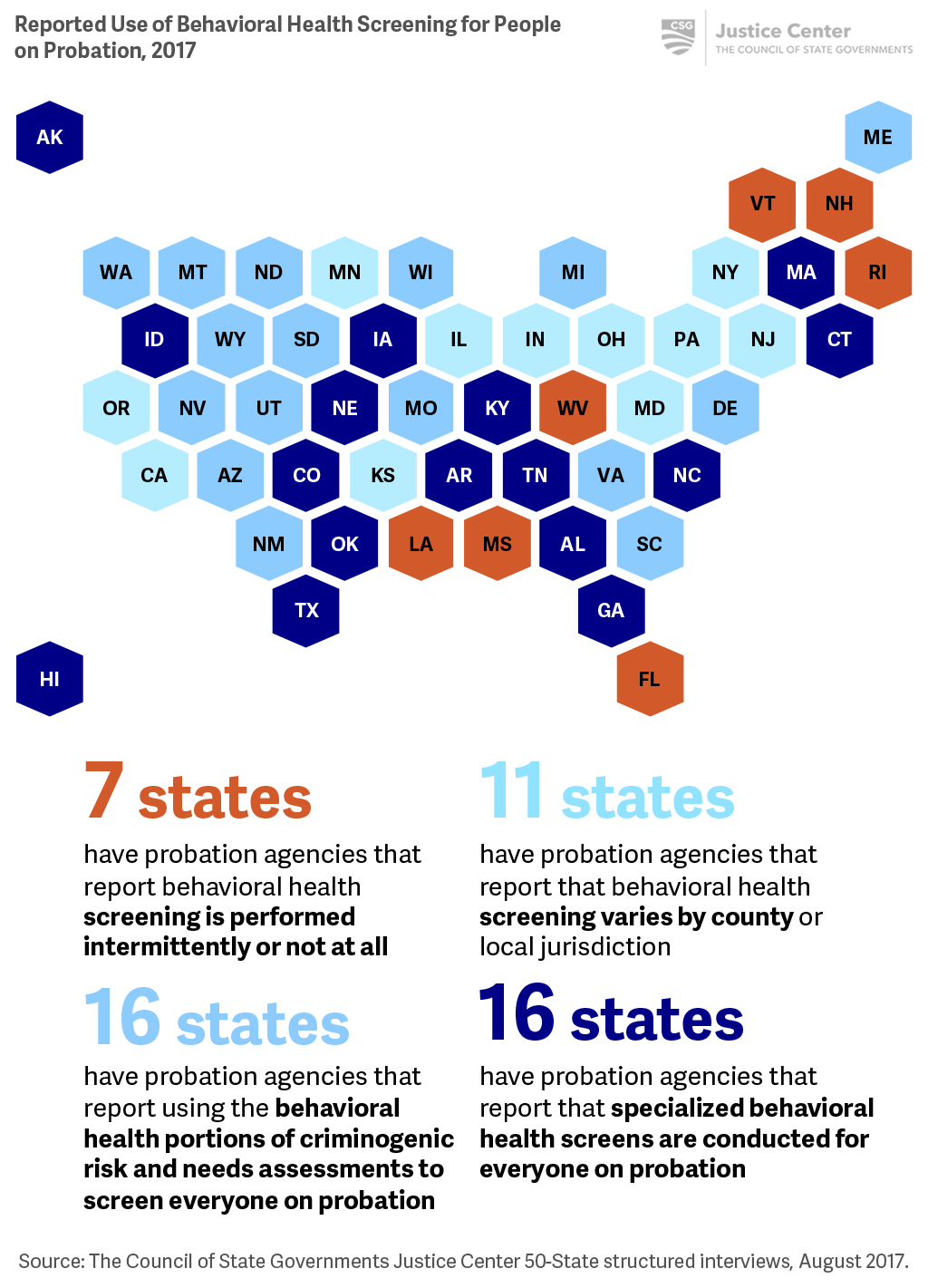

Shortly after a person enters the criminal justice system, and as needed thereafter, he or she should be screened by trained staff for substance addictions, mental illnesses, and the potential presence of both. Screening tools for substance addictions and mental illnesses are designed to quickly identify people who may have behavioral health needs. People who screen positive should receive a clinical assessment to confirm the presence of addictions and a recommendation for the appropriate type and level of services.

Criminogenic risk and needs should also be identified at the earliest stage of criminal justice involvement, and people should be reassessed over time using criminogenic risk and needs assessments to monitor changes in risk level and needs. The results of assessments of both behavioral health conditions and criminogenic risk and needs should be considered in developing comprehensive case plans to address a person’s health and criminogenic needs.

To learn more, see Adults with Behavioral Health Needs under Correctional Supervision: A Shared Framework for Reducing Recidivism and Promoting Recovery.

Measuring criminal justice system and behavioral health collaboration

The CSG Justice Center partnered with Dr. Faye Taxman from George Mason University’s Center for Advancing Correctional Excellence to develop guiding principles and process measures that can help gauge how well the criminal justice and behavioral health treatment systems are collaboratively addressing people’s behavioral health needs and guide cross-systems delivery of service. For additional information, see Process Measures at the Interface Between the Justice System and Behavioral Health: Advancing Practice and Outcomes.

Universal screening is critical to identifying people’s behavioral health needs. In 16 states, probation agencies report universal screening for behavioral health needs by using specialized behavioral health screening tools.

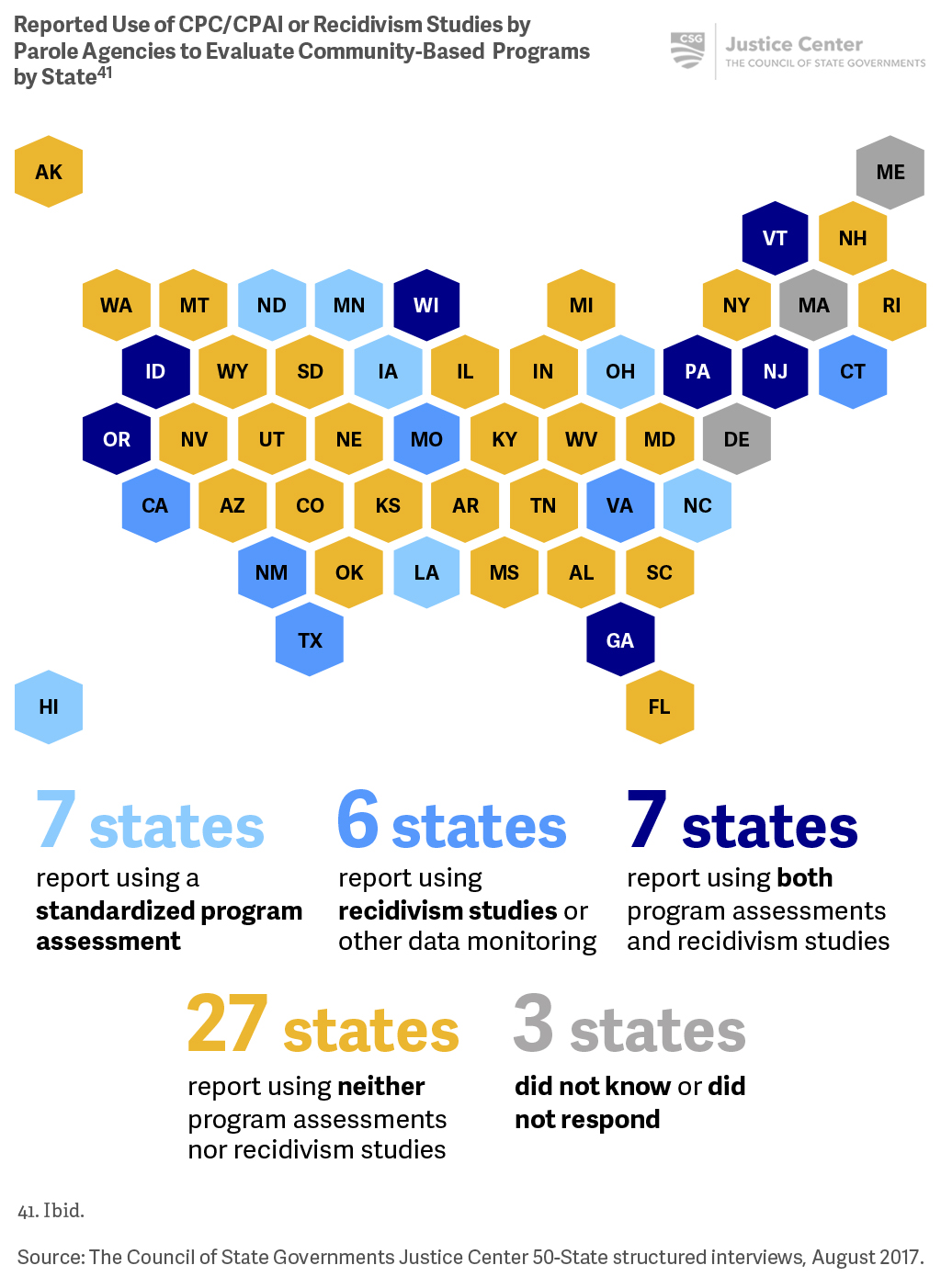

Fewer than half of states report that their probation agencies conduct evaluations of community programs and/or treatment provider outcomes, which are necessary to measure their quality and effectiveness.

Fewer than half of states report that their parole agencies conduct evaluations of community program and/or treatment provider outcomes, which are necessary to measure their quality and effectiveness.

Bonta and Andrews, The Psychology of Criminal Conduct.

Mark Lipsey, Nana Landenberger, Sandra Wilson, “Effects of a Cognitive-Behavioral Program for Criminal Offenders,” (Oslo: The Campbell Corporation, 2007).

Christopher T. Lowenkamp, Edward J. Latessa, and Paula Smith. “Does Correctional Program Quality Really Matter? The Impact of Adhering to the Principles of Effective Intervention” Criminology and Public Policy 5, no. 3 (2006): 575-594. 575-594.

Lipsey, Landenberger, and Wilson, Effects of a Cognitive-Behavioral Program for Criminal Offenders.ers.

Cognitive-behavioral interventions help people recognize situations that trigger unwanted behavior and cope with the thoughts and feelings that contribute to this behavior. Programs for the criminal justice population that use a cognitive behavioral approach can help people improve critical and moral reasoning, social skills, self-control, problem solving, and impulse control, and are most effective when they include structured social learning components where new skills, behaviors, and attitudes are consistently reinforced. Role-playing, cognitive skills training, anger management, moral development, and relapse prevention are common elements of these programs.[35]

[35] Lipsey, Landenberger, and Wilson, Effects of a Cognitive-Behavioral Program for Criminal Offenders.

Criminogenic risk and needs assessments use an actuarial evaluation to guide decision making at various points in the criminal justice continuum. These assessments approximate a person’s likelihood of reoffending and determine the individual dynamic factors that contribute to this likelihood, such as criminal thinking or attitude, that must be addressed to reduce that possibility.

Case Study

Iowa and Illinois prioritize use of effective programs

State corrections and supervision agencies need to place the right people in the right programs to reduce recidivism. To do that, these agencies need to assess which programs and services they offer, and how their program and service capacity aligns with the needs of their population and adjust programming accordingly.

In 2014, the Iowa Department of Corrections (DOC) received funding from the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance to engage in a comprehensive process to reduce recidivism through the Statewide Recidivism Reduction (SRR) program. As part of that effort, Iowa DOC targeted improving use of evidence-based practices for prison programming.

To ensure that all programs were adhering to evidence-based correctional practices, Iowa DOC staff conducted an inventory of more than 200 prison programs across all 9 of its facilities. More than one-third of those programs were not following the latest best practices and thus were defunded over the course of the three-year grant. Iowa DOC was then able to reallocate staff and resources to expand effective programming. Going forward, all state facilities will review programs every year to ensure that they are adhering to evidence-based practices and achieving positive outcomes.

In 2016, leaders of the Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) sought to determine whether treatment programs and services provided in IDOC facilities and the community were evidence based. They contracted with Southern Illinois University to implement the RNR Simulation Tool, [38] a web-based tool used to identify programming needs for people in the justice system within a jurisdiction and guide resource allocation to match programming to risk-need profiles. Using the RNR Simulation Tool’s program assessment, the IDOC was able to identify and discontinue programs that were not grounded in evidence—a cost-effective way to ensure that resources were spent on programs that have the greatest impact.

[38] “Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR) Simulation Tool,” George Mason University Center for Correctional Excellence, accessed June 14, 2017, https://www.gmuace.org/research_rnr.html.

Case Study

States establish measures to improve quality of programs

States have taken a variety of approaches to ensure they are funding the right programs with a focus on quality of delivery.

- In statute, Georgia now requires the Department of Corrections and the Department of Community Supervision to evaluate the quality of programming used in department facilities and day reporting centers, respectively, every five years and publish the results to ensure that programs are evidence-based and effectively reduce recidivism.[39]

- Montana authorized its Department of Corrections’ existing quality-assurance unit to adopt a validated program evaluation tool, evaluate state-funded programs, and enforce standards to ensure that programs are using best practices for reducing recidivism, including targeting people who are at a high risk of reoffending, adhering to evidence-based or research-driven practices, and integrating opportunities for ongoing quality assurance and evaluation.

- Ohio’s Department of Rehabilitation and Correction (DRC) requires service providers to utilize evidence-based practices to receive state funding. DRC conducts annual audits to ensure adherence to evidence-based practices and fidelity to treatment models proven to have an impact on recidivism reduction. DRC also provides training, coaching, and technical assistance to service providers to ensure compliance with standards. Failure to comply with standards or achieve a demonstrated increase in recidivism can result in a loss of funding.

[39] Georgia DOC has facilities called Probation Detention Centers (PDCs), residential substance abuse treatment programs (RSAT), and Integrated Treatment Facilities. The evaluation component applies to these facilities and not programming they offer in prisons.

Case Study

Idaho overhauls programs after in-depth assessment

After Idaho enacted Justice Reinvestment legislation in 2014, the Idaho Department of Corrections (IDOC) requested that the CSG Justice Center perform a comprehensive program assessment to determine whether the nearly $10 million the state was spending on these programs was maximizing the potential to reduce recidivism. As part of the six-month long Justice Program Assessment (JPA) process, CSG Justice Center staff analyzed how the state was spending money on programming, conducted on-site observations of programming, and assessed IDOC’s capacity to ensure quality control.

The JPA evaluation revealed that Idaho conducted risk and needs assessments at every decision point in the system, but they did not use assessment results to prioritize programming for people at the highest risk of reoffending. Instead, people of all risk levels were treated together in programs, which research indicates is an ineffective practice for reducing recidivism. Additionally, three-quarters of the program curricula being used were outdated or were no longer considered to be the most effective for helping to reduce recidivism. Further, Idaho’s therapeutic communities were using practices that research shows are ineffective.

Based on this analysis, CSG Justice Center staff recommended that Idaho establish greater differentiation in its approach, providing more intensive programming for people at a high risk of reoffending; replace outdated program curricula with cognitive behavioral programs more likely to reduce recidivism; and use trained IDOC staff to carry out evaluations of prison and community-based programs to monitor the quality of those programs moving forward. As a result of the JPA recommendations, IDOC streamlined its program offerings to five core risk-reduction programs that are available in all facilities—all of which adhere to principles that decrease a person’s likelihood of reoffending—and trained approximately 1,000 staff members on evidence-based programs.