Part 1, Strategy 2

Action Item 1: Improve the identification of people who have behavioral health needs in the criminal justice system.

Why it matters

Currently, many state and county criminal justice agencies cannot accurately identify how many people in their custody have behavioral health needs because they don’t routinely use validated universal behavioral health and criminogenic screening and assessment tools. Without this information, criminal justice agencies cannot develop effective case plans for people who have behavioral health needs. Further, criminal justice agencies can’t successfully implement agency-wide—or even criminal justice system-wide—strategies to improve recovery and reduce recidivism.

Criminal justice agencies’ practices vary greatly across the country; some agencies do not screen anyone for behavioral health needs, while others may screen only some people. Other agencies may conduct clinical assessments for everyone instead of targeting the use of specialized assessments through universally conducted initial screenings. Criminal justice agencies may not use shared definitions across agencies for serious mental illnesses and substance addictions, which increases the difficulty of identifying people who need treatment, and makes data sharing between agencies more challenging. In turn, this limits collaboration, continuity of care, and the potential for improved outcomes.

What it looks like

- Establish standardized definitions of serious mental illnesses and substance addictions for people in the criminal justice system to improve consistency and collaboration between criminal justice and behavioral health agencies.

- See Case Study: Ohio establishes a standard definition of serious mental illness for criminal justice systems

- Provide funding and establish standards for training for law enforcement officers to identify people who may have behavioral health needs and respond appropriately.

- See Case Study: Implementing Crisis Intervention Team Training in Ohio

- Require universal screening using a validated tool when people are booked into jail or prison or placed on supervision, and follow up with a comprehensive clinical assessment for those who screen positive for a behavioral health need.

- Provide guidance and statutory clarification to encourage and facilitate information sharing within and across criminal justice and behavioral health agencies.

- See Case Study: California develops guidelines for counties on sharing behavioral health information

Key questions to guide action

- What can your state do to promote universal screening and assessment processes using validated tools to identify people who have mental illnesses and substance addictions across the criminal justice system?

- Do criminal justice agencies in your state use shared definitions for serious mental illnesses and substance addictions across the state? If not, can the state support local jurisdictions in identifying shared definitions?

- How can your state improve behavioral health data collection, analysis, and information sharing between state and local criminal justice and behavioral health agencies to strengthen strategic planning, increase access to treatment and supports, and improve outcomes?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

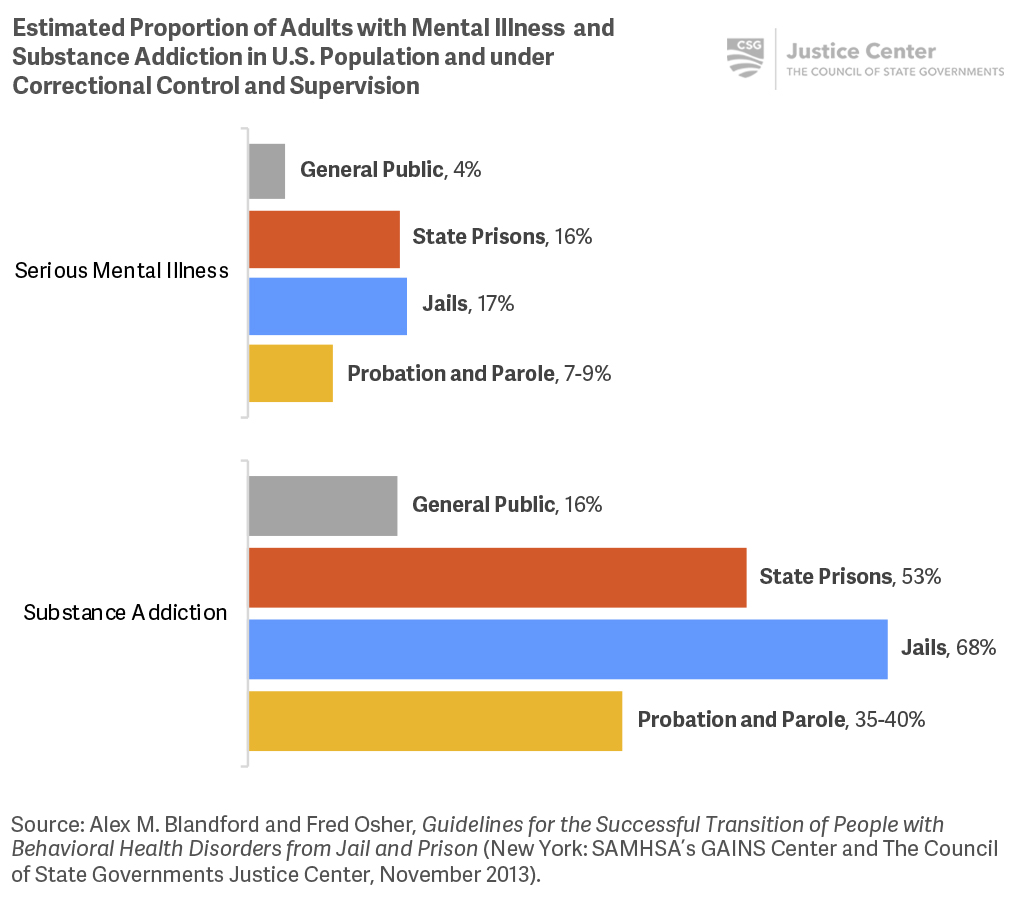

The proportion of people in the criminal justice system who have a serious mental illness or substance addiction is greater than for the general public.

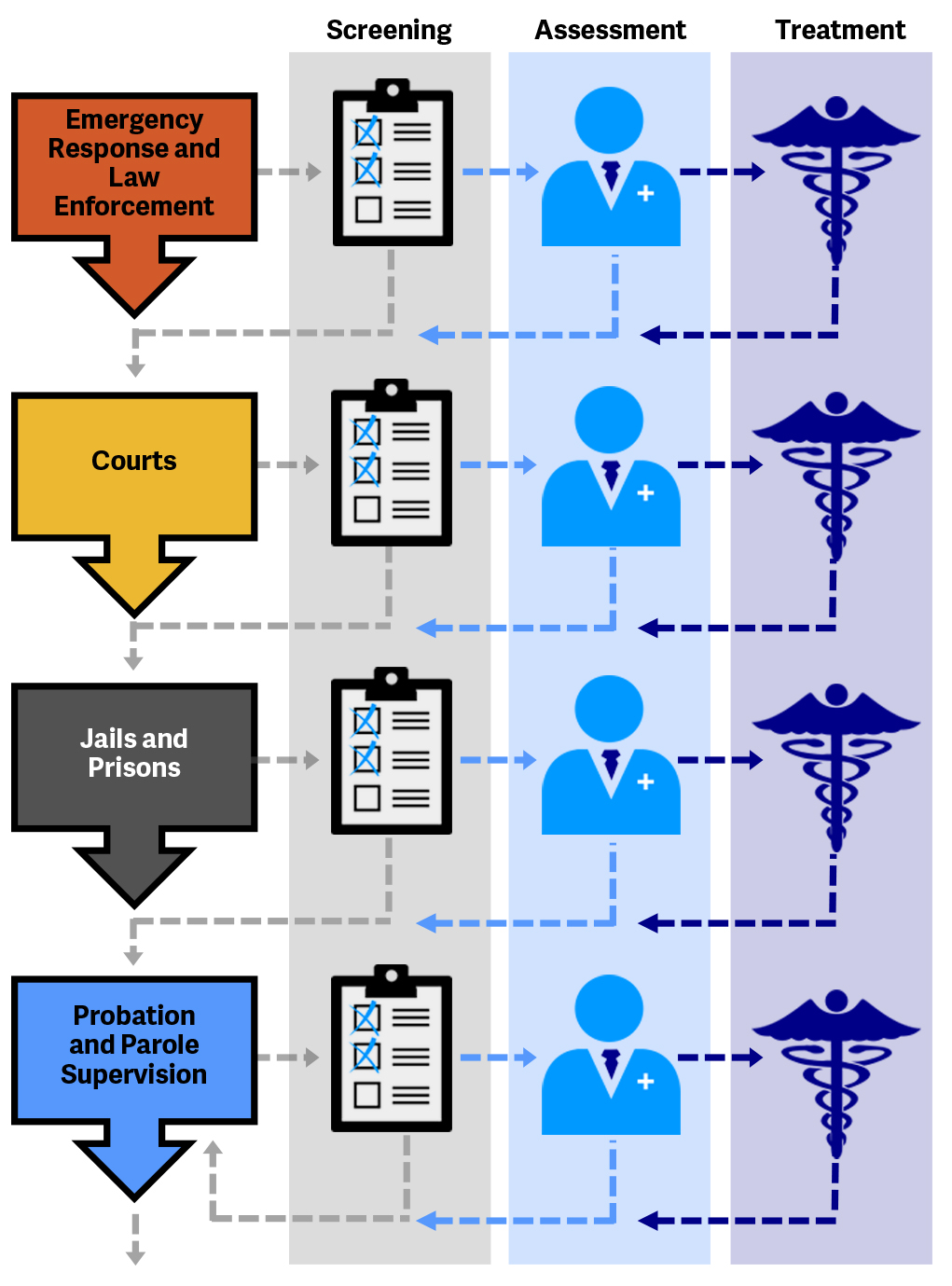

People who have behavioral health needs can be identified with screening and assessment at different stages of the justice system.

Additional Resources

Screening and Assessment

Shortly after a person enters the criminal justice system, and as needed thereafter, he or she should be screened by trained staff for addictive disorders, mental illnesses, and the potential presence of both. Screening tools for substance use and mental illnesses are designed to quickly identify people who may have behavioral health needs. People who screen positive should receive a clinical assessment to confirm the presence of disorders and a recommendation for the appropriate type and level of services.

Criminogenic risk and needs should also be identified at the earliest stage of criminal justice involvement, and people should be reassessed over time using criminogenic risk and needs assessments to monitor changes in risk level and needs. (For additional information on criminogenic risk and needs assessments, see also Part 2, Strategy 2.) The results of assessments of both behavioral health conditions and criminogenic risk and needs should be considered in developing comprehensive case plans to address a person’s behavioral health and criminogenic needs.

To learn more, see Adults with Behavioral Health Needs Under Correctional Supervision: A Framework for Reducing Recidivism and Promoting Recovery.

Additional Resources

Stepping Up

Since May 2015, 400 counties have passed resolutions to join Stepping Up, a national initiative to reduce the number of people who have mental illnesses in jails. Recognizing the critical role local and state officials play in supporting change, the National Association of Counties (NACo), The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center, and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation (APAF) are leading this unprecedented national initiative.

NACo, the CSG Justice Center, and APAF are working with partner organizations to build on the foundation of innovative and evidence-based practices already being implemented across the country, and bring these efforts to scale. These partners have expertise in the complex issues addressed by Stepping Up and include sheriffs, jail administrators, judges, community corrections professionals and treatment providers, consumers, advocates, behavioral health directors, and other stakeholders.

Reducing the Number of People with Mental Illnesses in Jail: Six Questions County Leaders Need to Ask serves as a blueprint for counties to assess their existing efforts to reduce the number of people who have mental illnesses and co-occurring substance addictions in jail by considering specific questions and progress-tracking measures.

The six questions county leaders need to ask are:

- Is your leadership committed?

- Do you have timely screening and assessment?

- Do you have baseline data?

- Have you conducted a comprehensive process analysis and service inventory?

- Have you prioritized policy, practice, and funding?

- Do you track progress?

The Stepping Up County Self-Assessment is an online tool designed to help counties evaluate the status of their current efforts to reduce the prevalence of people who have mental illnesses in jails. The tool helps counties identify progress they have made in implementing system-level changes and provides resources on how to implement changes that they may find challenging.

Additional information about Stepping Up can be found here.

Criminogenic risk and needs assessments are actuarial tools that approximate a person’s likelihood of reoffending and determine the individual dynamic factors that contribute to the likelihood of reoffending, such as criminal thinking or attitude, that must be addressed to reduce that likelihood.

Case Study

Ohio establishes a standard definition of serious mental illness for criminal justice systems

Following the Ohio Stepping Up Summit in June 2016, the Stepping Up Ohio Statewide Steering Committee identified the need for a standard definition of serious mental illness (SMI) for use by Ohio counties participating in Stepping Up, a national initiative to reduce the number of people who have mental illnesses in jails. Establishing a standard definition for jails was deemed a priority to ensure clear and consistent data collection and sharing between county jails and county behavioral health systems.

In 2017, Ohio adopted the following definition of serious mental illness and recommended that counties participating in Stepping Up adopt it for use in jails: “a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder of an individual age 18 or older (excluding developmental, neurocognitive, and substance use disorders) that is currently diagnosable or has been diagnosed in the past year, of sufficient duration to meet diagnostic criteria specified within the most current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and resulting in serious functional impairments which interferes with one or more major life activities. Such disorders would include but not be limited to:

- Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders;

- Bipolar disorders;

- Major depressive disorders of at least moderate severity or with psychotic features;

- Obsessive-compulsive disorders;

- Panic disorder; or

- Post-traumatic stress disorder.

These conditions may exist with co-occurring developmental, neurocognitive and/or substance use disorders.”[32]

The state notes that the definition “is intended to provide counties with a frame of reference that they can use to then begin identifying SMI clients that come into contact with the criminal justice system. The hope is to assist counties in being able to identify these clients promptly and aid them to better meet their needs and to also develop a system to track or better track the number of SMI clients entering the criminal justice system for data collection and to further track progress.”[33]

[32] Tracy J. Plouck (Director, Ohio Department of Mental Health & Addiction Services), “Working definition of serious mental illness” memorandum to Members of the Stepping Up Ohio Statewide Steering Committee and County Coordinators for Stepping up Ohio, November 8, 2017.

[33] Email correspondence between CSG Justice Center and Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services staff, April 2017.

Case Study

Implementing Crisis Intervention Team Training in Ohio

Since 2001, the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services has funded the Ohio Criminal Justice Coordinating Center of Excellence (CJCCoE) to promote alternatives to jail for people who have mental illnesses throughout the state. In collaboration with the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Ohio, CJCCoE implements Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) programming and training across the state; by November 2017, nearly all of Ohio’s counties (86 of 88) had trained CIT officers.[34]

The state’s ultimate goal is to have a fully developed CIT program in every county, with every law enforcement agency within each county participating. CJCCoE also created a statewide strategic plan that identifies strategies beyond basic training and proposes investments by state and local governments that will strengthen CITs across Ohio, including: (1) ensuring that each CIT program has a law enforcement and a mental health coordinator; (2) providing mental health crisis centers where CIT officers can take people for assessment and care; and (3) training for 911 call-takers and dispatchers.[35] As described in the strategic plan, CJCCoE and NAMI Ohio provide technical assistance to enhance the CIT program in each community.

[34] Ohio Criminal Justice Coordinating Center of Excellence (CJCCoE), Cumulative State of Ohio CIT Training Report: Crisis Intervention Team Training, May 2000–January, 2018 (Rootstown, OH: CJCCoE, January 2018).

[35] CJCCoE, Ohio Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) Strategic Plan (Rootstown, OH: CJCCoE, August 2015).

Case Study

California develops guidelines for counties on sharing behavioral health information

Misunderstanding and uncertainty regarding federal regulations related to health information-sharing (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act [HIPPA] and 42 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] Part 2) has created barriers to appropriate information sharing among criminal justice and behavioral health agencies.

In 2017, the California Office of Health Information Integrity, which has statutory authority to interpret and clarify state law, created the State Health Information Guidance (SHIG), authoritative but non-binding guidance that clarifies state and federal laws governing the sharing of mental health and substance addiction information between behavioral health care providers and public health authorities, social service case managers and coordinators, law enforcement officers and other first responders, and caregivers. The SHIG is written in plain language and explains when, where, and why behavioral health information can be shared with the “triple aim” of improving patient outcomes, overall patient satisfaction, and efficiency.

The SHIG is intended for a general audience and includes 22 case examples that clarify how laws apply to real situations, such as those involving general and behavioral health care providers, emergency service providers, law enforcement, and other parties.