Part 1, Strategy 3

Action Item 2: Adopt policies that improve pretrial decisions and reduce burdens on jails.

Why it matters

Three out of five people in jail nationwide are awaiting trial for the crime for which they have been booked and charged.[61] Detaining low- and moderate-risk people pretrial can have a negative impact on their lives and on public safety. Pretrial detention can threaten a person’s employment, housing stability, and access to health care, as well as hinder a defendant’s ability to prepare his or her defense. One study found that defendants released within three days of a bail hearing were more likely to be employed and earn more in the two years after a bail hearing compared to those who are initially detained for more than three days after a bail hearing.[62] Studies show that even short periods of pretrial detention are associated with an increase in the likelihood that a defendant will be sentenced to jail or prison, and people who are detained pretrial receive significantly longer sentences than those who are not.[63] Detaining low- and moderate-risk people pretrial can make them more likely to reoffend, even after just two or three days in jail.[64]

Pretrial risk assessments that assess for risk of rearrest and failure to appear in court help judges make appropriate release decisions and determine whether there should be any conditions of release, such as supervision, drug testing, or electronic monitoring. Objective risk assessments have been shown to be more reliable than a professional’s individual judgment. While a pretrial risk assessment should not be the sole factor in making release decisions, it is currently the best available method for ensuring consistent, research-based decision making.

Risk assessment tools must be routinely validated in any jurisdiction in which they are used to ensure their accuracy. Validation studies should examine the instrument’s ability to identify groups of people with different probabilities of failing to appear in court or engaging in criminal activity, including assuring accuracy across racial groups and by gender, as well as overall population.

As jurisdictions adopt pretrial risk assessments, some are also reducing or eliminating the use of bond schedules that determine financial bail requirements based on criminal charges rather than assessed risk of offending or failure to appear in court. The use of bond schedules may lead to people who commit more serious crimes, but can afford bail, being released from jail, and people who commit less serious offenses, but can’t afford bail, being detained pretrial. This approach puts public safety at risk if people are released due to financial considerations instead of their assessed risk. Bond schedules have also been challenged in court as unconstitutionally keeping defendants in jail because they are too poor to post bail.[65]

Jurisdictions are increasingly turning to pretrial services as a valuable complement to pretrial risk assessment. Using the least restrictive means necessary to ensure appearance in court and promote public safety, pretrial services staff can remind people of upcoming court dates and support their compliance with any conditions the court may require when authorizing their release, such as meeting with pretrial supervision staff, forbidding contact with certain individuals, or complying with curfews, electronic monitoring, or drug testing.

Policies that make admission to jail more likely or increase length of stay often increase the number of people in jail, potentially straining local resources without necessarily increasing public safety. When considering policies that could increase jail populations, policymakers need to assess the policies’ potential impact on public safety and determine whether there are alternative approaches that would further public safety goals without adding pressures to local jails or whether there are ways to provide support to counties to mitigate the impact of these policies.

States can also establish policies and provide funding to support local efforts to use jail space cost-effectively, including supporting efforts to divert people from jail who have behavioral health needs and are accused of minor offenses, when appropriate, engage the prosecution and defense counsel early in the court process, and issue guidance on the use of citations in lieu of arrest. State policies can reduce pressures on jail populations and increase public safety by ensuring that the right people are detained pretrial based on risk assessment results. Ultimately, these policies benefit states by reducing crime, victimization, and the number of people who enter state prisons.

What it looks like

- Require use of a validated pretrial risk assessment tool.

- See Case Study: Validating risk assessments improves outcomes

- Provide funding to increase adoption of risk assessments, as needed.

- See Case Study: States support local use of risk assessment

- Establish clear criteria with due process protections for pretrial detention based on risk, and eliminate use of bond schedules.

- Establish and support pretrial services.

- See Case Study: New Jersey pretrial reform reduces statewide jail population

- Promote use of citation in lieu of arrest.

- See Case Study: States authorize use of citation in lieu of arrest

- Promote court and jail-based diversion by statutorily defining eligibility for diversion and establishing timing of appointment of counsel.

- Fund local diversion approaches for people who have behavioral health needs that demonstrate alignment with locally identified needs, gaps, and circumstances.

- Provide resources to support the prosecution’s and defense counsel’s engagement prior to initial court appearances.

- See Case Study: Texas supports local assignment of counsel at first appearance

Key questions to guide action

- What more could your state do to support use of pretrial risk assessments and reduce reliance on bail schedules?

- How could your state support pretrial services?

- How does your state support the prosecution’s and defense counsel’s engagement prior to initial court appearances?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

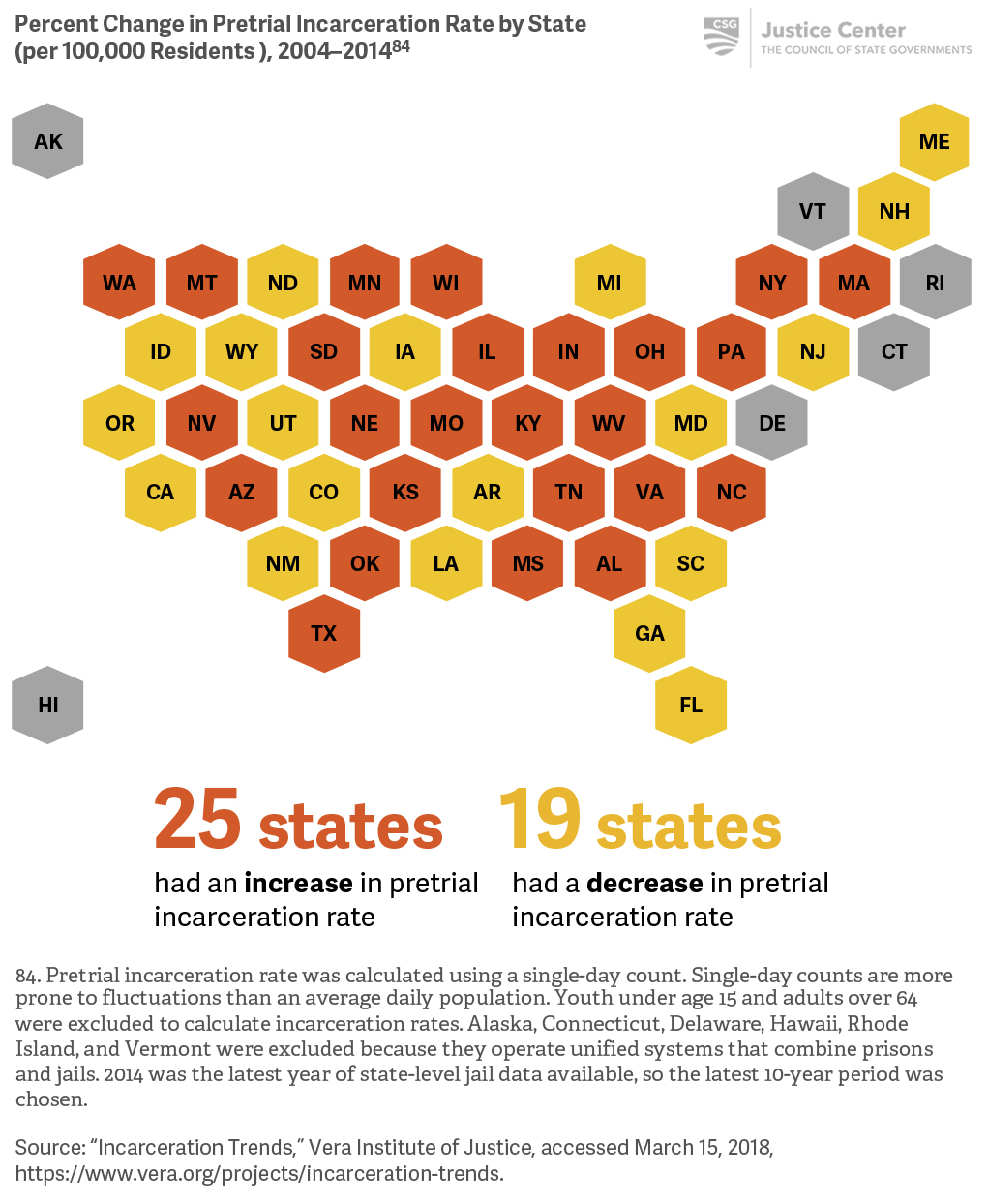

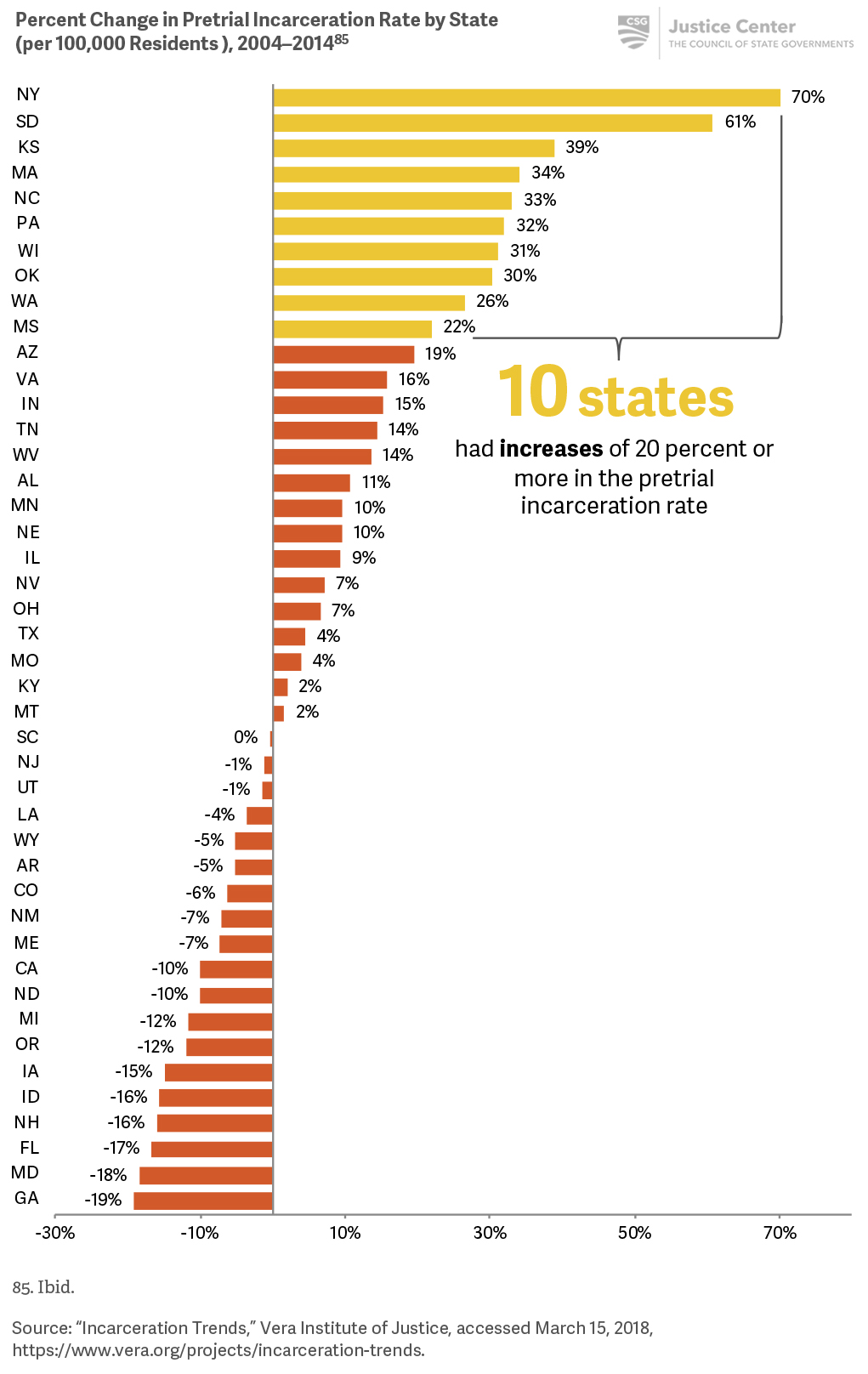

Pretrial incarceration rates have increased in 25 states and fallen in 19 states.

Changes in pretrial incarceration rates vary widely across states.

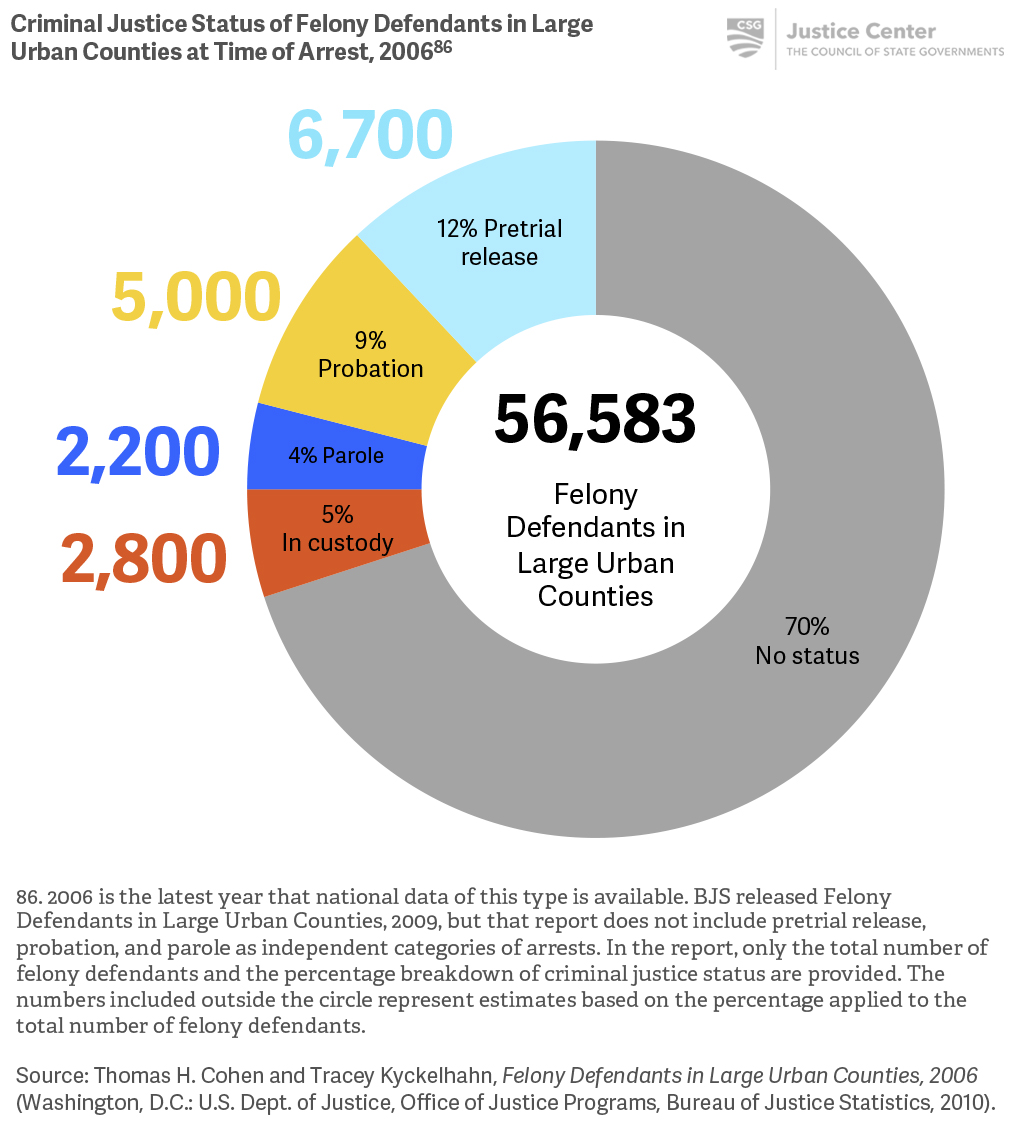

While most people who are arrested do not have a criminal justice status, of those who do, the majority are on pretrial release at time of their arrest for a felony offense.

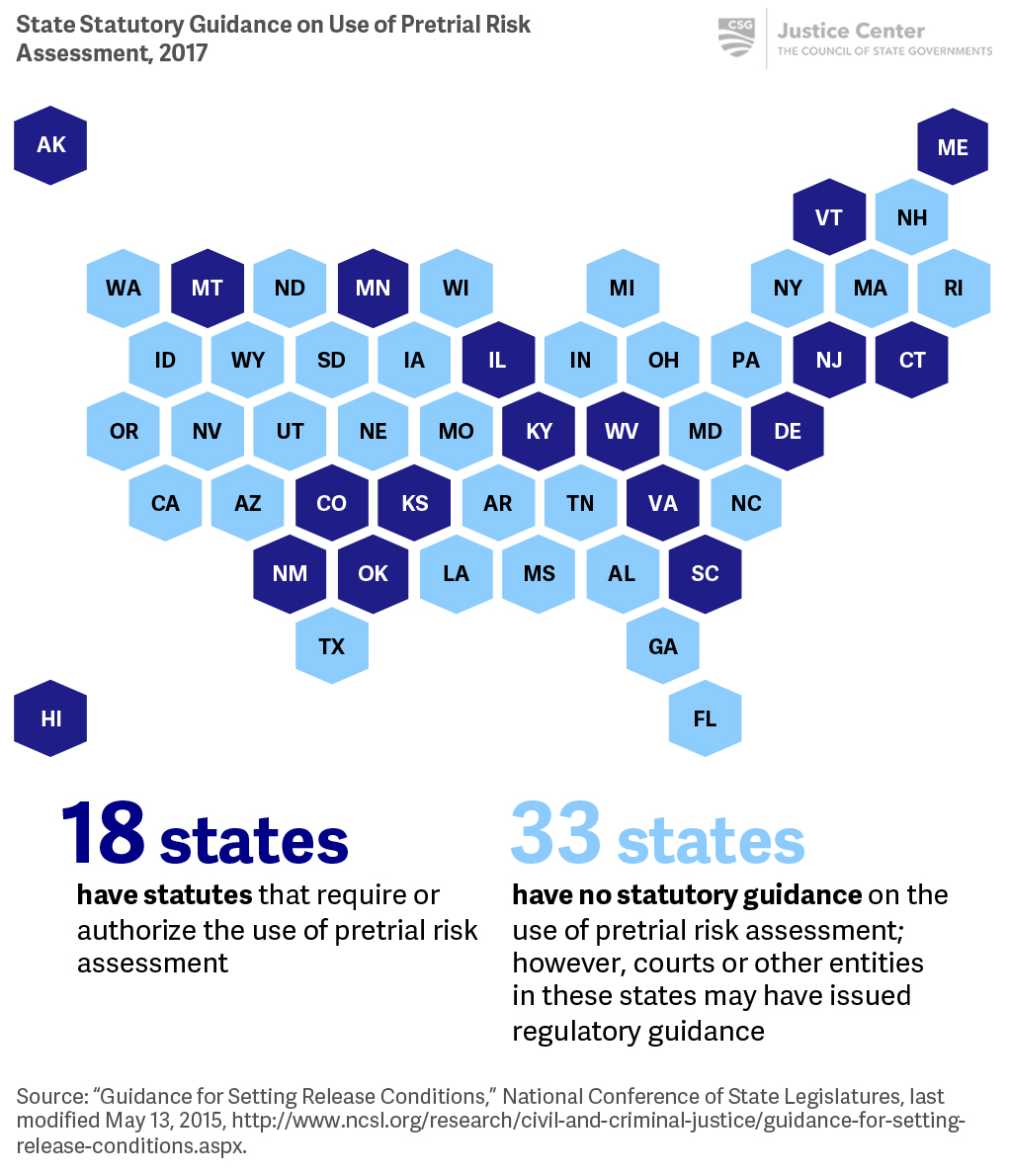

18 states have passed legislation to require or authorize the use of pretrial risk assessment.

Additional Resources

Safety and Justice Challenge

The Safety and Justice Challenge provides support to local leaders from across the country to establish alternatives to jail incarceration. With an initial 5-year, $100 million investment by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, cities, counties, and states selected through a competitive process receive financial and technical support in their efforts to rethink justice systems and implement data-driven strategies to safely reduce jail populations. For additional information, see Safety and Justice Challenge.

Public Safety Assessment

Pretrial risk assessment tools assess for risk of rearrest and failure to appear in court, and some tools, including the Public Safety Assessment (PSA), assess for risk of new violent criminal activity. The Laura and John Arnold Foundation created the PSA to assist judges in making release decisions. For additional information, see Public Safety Assessment.

3DaysCount

Research shows that even three days in jail can make low-risk defendants less likely to appear in court and more likely to commit new crimes.[87] The Pretrial Justice Institute created 3DaysCount, a nationwide initiative to reduce arrests, replace money bail with risk-based decision making, and restrict detention (after due process) to people who pose unmanageable risks if released. For additional information, see 3DaysCount.

University of Pretrial

The University of Pretrial offers a range of resources, learning opportunities, and forums for criminal justice stakeholders to share information about pretrial justice-related topics. For additional information, see University of Pretrial.

Todd D. Minton and Zhen Zeng, Jail Inmates, 2015.

Will Dobbie, Jacob Goldin, and Crystal Yang, “The Effects of Pretrial Detention on Conviction, Future Crime, and Employment: Evidence from Randomly Assigned Judges,” American Economic Review 108, no. 2 (2018): 214, https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1257/aer.20161503.

Laura and John Arnold Foundation, Research Summary: Pretrial Criminal Justice Research (New York: Laura and John Arnold Foundation, 2013).

Ibid.

Varden v. City of Clanton, Case No. 2:15-cv-34-MHT-WC (M.D. Ala., Feb. 13, 2015).

Laura and John Arnold Foundation, Research Summary: Pretrial Criminal Justice Research.

Case Study

Validating risk assessments improves outcomes

By 2005, all Virginia pretrial services agencies were using the Virginia Pretrial Risk Assessment Instrument (VPRAI) to estimate the likelihood of rearrest and failure to appear in court and to assist pretrial officers in making a bail recommendation. All defendants who were arrested and booked into county jails were assessed by pretrial services staff within seven days of booking. In 2007, a validation study was conducted on the tool that showed it appropriately categorized people charged with offenses by risk level and accurately predicted pretrial behavior, but also showed that accuracy could be improved by removing a question asking if a person had outstanding warrants since that question was not a statistically significant predictor of pretrial outcomes.[66] As a result, Virginia removed this question from the tool.

In 2009, Multnomah County (Portland), Oregon’s pretrial services agency began using the VPRAI.[67] The agency compared the VPRAI’s Virginia validation population with a sample of local defendants and found significant differences in age, ethnicity, residence of less than one year, employment during the past two years, and current charge level. After Multnomah’s pretrial agency implemented the VPRAI, the agency validated the assessment against the local population and made appropriate changes to match the county’s defendant population and charging practices.[68]

[66] Marie VanNostrand and Kenneth J. Rose, The Virginia Pretrial Risk Assessment Instrument (St. Petersburg, FL: Luminosity, Inc., May 2009).

[67] Don Trapp (Community Justice Manager, Multnomah County, Adult Services Division Pretrial Services Program), “Norming the Virginia Pretrial Risk Assessment for application in Multnomah County,” memorandum to William Penny (District Manager, Multnomah County, Adult Services Division Pretrial Services Program), July 6, 2010.

[68] Lisa Pilnik et al., A Framework for Pretrial Justice: Essential Elements of an Effective Pretrial System and Agency (Washington, DC: The National Institute of Corrections, February 2017).

Case Study

States support local use of risk assessment

State leaders are increasingly recognizing an opportunity to improve public safety and reduce jail population pressures by supporting the use of pretrial risk assessments through a variety of means, including requiring use of pretrial risk assessments, funding grants to adopt these assessments, and establishing pretrial supervision agencies.

- Alaska required the Department of Corrections to adopt and validate a pretrial risk assessment tool and hire pretrial service officers to conduct risk assessments prior to a defendant’s first appearance in court, with recommendations on the appropriateness of release on recognizance and the appropriateness of pretrial supervision.

- Hawaii requires timely risk assessments of pretrial defendants to lessen costly delays in the pretrial process and expedite release of low-risk people.

- Maine requires a domestic violence risk assessment for defendants accused of domestic violence to be considered in pretrial release decisions.

- Montana has offered grant funding to incentivize counties to adopt a pretrial risk assessment tool for pretrial defendants and a dangerousness and/or lethality assessment for people charged with domestic violence offenses, and to provide monitoring and supervision of pretrial defendants who have been assessed as being at a high risk of reoffending.

- New Mexico’s constitution was amended in 2016 to allow district court judges to deny pretrial release for people accused of felonies who are proven likely, by clear and convincing evidence, to be a danger at a pretrial release hearing, and required that pretrial release and detention decisions be based on evidence of risk of rearrest or failure to appear in court instead of ability to pay bail. The New Mexico Supreme Court updated court rules to comply with the constitutional requirements in 2017 and will decide in 2018 which pretrial risk assessment courts should use.[69]

- Ohio’s Lucas County adopted a pretrial risk assessment tool in 2015, which helped the county keep its jail population under a court-imposed cap, while reducing both pretrial crime and missed court hearings. Prior to adoption of the tool, people could be released as an “emergency release” to ensure the jail population stayed under the court-imposed cap.[70]

[69] “Pretrial Release and Detention Reform,” The Judicial Branch of New Mexico, https://www.nmcourts.gov/pretrial-release-and-detention-reform.aspx.

[70] Laura and John Arnold Foundation, “New data: Pretrial risk assessment tool works to reduce crime, increase court appearances,” news release, August 8, 2016.

Case Study

New Jersey pretrial reform reduces statewide jail population

In October 2012, 73 percent of the 13,000 people in New Jersey’s jails were awaiting trial, and more than 38 percent of the total jail population had the option to post bail, but could not.[71] This meant that many people who were at a low risk of reoffending spent extended time in jail while some people at a high risk who could afford bail avoided detainment. Keeping people in jail pretrial costs counties approximately $6,000 to $9,000 per pretrial defendant.[72]

In 2014, New Jersey passed comprehensive bail reform that went into effect on January 1, 2017. The legislation makes the pretrial process more cost effective for taxpayers and fairer to people who have not yet been convicted of a crime.

- The courts are required to use an evidence-based risk assessment tool when making release decisions.[73]

- The courts have the discretion to release people to pretrial supervision, which may involve check-in calls, in-person meetings, or GPS monitoring, and is overseen by the newly established statewide pretrial services agency.[74]

- People can be held no more than 48 hours before the court makes a pretrial release decision, and no more than 180 days before trial commences.[75]

To assist with implementation of the law, the state established the “21st Century Justice Improvement Fund” and annually allocates $44 million from court fees for the development, maintenance, and administration of the pretrial services program and a statewide digital court database, as well as the provision of legal assistance to the poor on civil matters.[76] Within the first year of implementation of the bail reform legislation, 81 percent of the 44,319 defendants were released pretrial, and the number of people being held in jail pretrial dropped more than 20 percent.[77] Despite initial successes, the courts warn that funding pretrial services through court fees is unsustainable and recommends a dedicated funding stream through the General Fund.[78]

[71] Marie VanNostrand. New Jersey Jail Population Analysis: Identifying Opportunities to Safely and Responsibly Reduce the Jail Population (St. Petersburg, FL: Luminosity, Inc. March 2013).

[72] Report of the Joint Committee on Criminal Justice, March 2014. http://judiciary.state.nj.us/pressrel/2014/FinalReport_3_20_2014.pdf. The report estimates it costs jails an average of $100 per day to house someone pretrial and the average person stays in jail for 60-90 days pretrial.

[73] NJ Rev Stat § 2A:162-15 (2014).

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Glenn Grant, Jan 1–Dec 31, 2017: Report to the Governor and the Legislature (Trenton, NJ: NJ Administrative Office of the Courts, February 2018).

[78] Ibid.

Case Study

States authorize use of citations in lieu of arrests

Citation in lieu of arrest has been widely embraced as a law enforcement tool. Nearly 87 percent of law enforcement agencies across the country give officers discretion to issue citations in lieu of arrest for low-level offenses, as defined by the state.[79] A citation is a written order that requires a person accused of committing an offense to appear at a designated place on a specified date, but allows the officer to release the person without transport to the police station, formal booking, and fingerprinting. A national survey showed that law enforcement agencies use citation for nearly a third of all incidents, most often for disorderly conduct, theft, trespassing, driving with a suspended license, and possession of marijuana.[80]

Twenty-four states have created a presumption to issue citations in lieu of arrest for misdemeanor crimes or petty offenses, while four states—Alaska, Louisiana, Minnesota, and Oregon—have expanded the law to permit citations for certain felony offenses.[81] State laws guide the circumstances under which a citation can be issued, which are often determined by the class of the alleged offense and are subject to exceptions:

- Alabama has limited its use of citations to Class C and traffic misdemeanors but exempts offenses that involve violence or result in injury.

- Kentucky has created a presumption that officers issue citations for misdemeanor offenses prior to arrest, but exempts impaired driving, assault, sexual crimes, and domestic violence crimes.

- Wyoming gives its officers broad discretion to issue citations in lieu of arrest for all misdemeanors, but exempts vehicular homicide, impaired driving, and failure to stop at an accident resulting in injuries.

[79] International Association of Chiefs of Police, Citation in Lieu of Arrest: Examining Law Enforcement’s Use of Citation Across the United States (Alexandria, Virginia: International Association of Chiefs of Police in collaboration with Laura and John Arnold Foundation, April 2016).

[80] Ibid.

[81] “Citation In Lieu of Arrest,” National Conference of State Legislatures, updated October 23, 2017, http://www.ncsl.org/research/civil-and-criminal-justice/citation-in-lieu-of-arrest.aspx.

Case Study

Texas supports local assignment of counsel at first appearance

The Texas Indigent Defense Commission (TIDC) provides financial and technical support to counties to develop and maintain high-quality, cost-effective indigent defense systems. The Bexar County Public Defender’s Office (BCPDO), in San Antonio, was awarded a grant from TIDC in 2015 for the public defender to provide representation upon the first appearance before a magistrate for people who have mental illnesses and are determined to be indigent. Between 2015 and 2017, the number of people granted mental health personal recognizance bonds when counsel was present more than tripled.[82] Clients who were represented by the BCPDO upon their first appearance before a magistrate were also observed to have a greater incidence of judicial and treatment compliance than those not represented by counsel.[83]

[82] Bexar County Public Defender’s Office, “Defense Counsel at Magistration: Benefits for Defendants with Mental Illness or Intellectual or Developmental Disabilities” (PowerPoint presentation, Texas Indigent Defense Commission

2nd Annual Texas Roundtable on Representation of Defendants with Mental Illness, Austin, TX, November 17, 2017).

[83] Ibid.