Part 1, Strategy 4

Action Item 3: Provide law enforcement officers with the necessary tools and resources to respond to the needs of their communities.

Why it matters

The role of law enforcement officers has changed dramatically over the last 20 years. In addition to responding to and preventing crime, officers now have added challenges, including de-escalating situations with people experiencing mental health crises, caring for people who have overdosed on opioids, and connecting community members to services. These new responsibilities cause new strains on officer wellbeing, requiring new resources to help officers manage their own secondary trauma and remain successful and healthy in the field.

- Specialized training in responding to people who have behavioral health needs and the development of Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) have provided promising evidence of reducing the arrest rate of people who have mental illnesses, increased transfers to local hospitals, reduced use-of-force encounters, and in some instances, increased use of mental health services for a 12-month period after a CIT encounter.[100]

- Access to naloxone kits and training on how to use them have helped law enforcement officers save thousands of lives across the country. Studies have shown that opioid deaths can be reduced by 27 to 46 percent in communities that couple naloxone use with overdose education.[101]

- Connecting people to services as a result of a police encounter in lieu of sending them to jail (when appropriate) can have a meaningful impact on the likelihood of future law enforcement encounters for those people.[102] (For additional information, see Part 1, Strategy 2.)

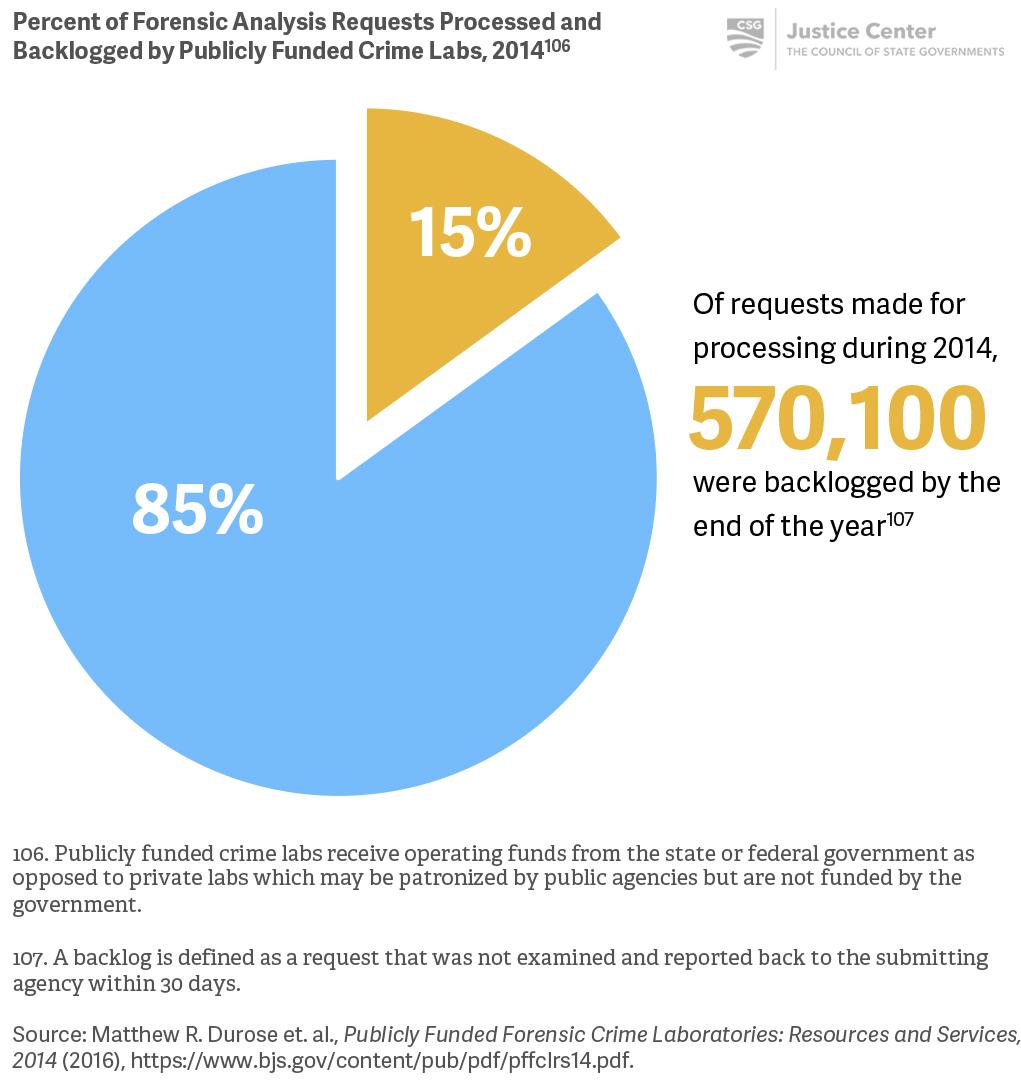

- Addressing backlogs at publicly funded crime labs can help law enforcement agencies investigate crimes more effectively and assist in reducing time between the commission of a crime and the clearance of cases.

- Ongoing training coupled with resources and support for officer physical and mental wellness can reduce incidents of suicide, help manage PTSD and depression, and facilitate more positive interactions with community members in the field.[103]

What it looks like

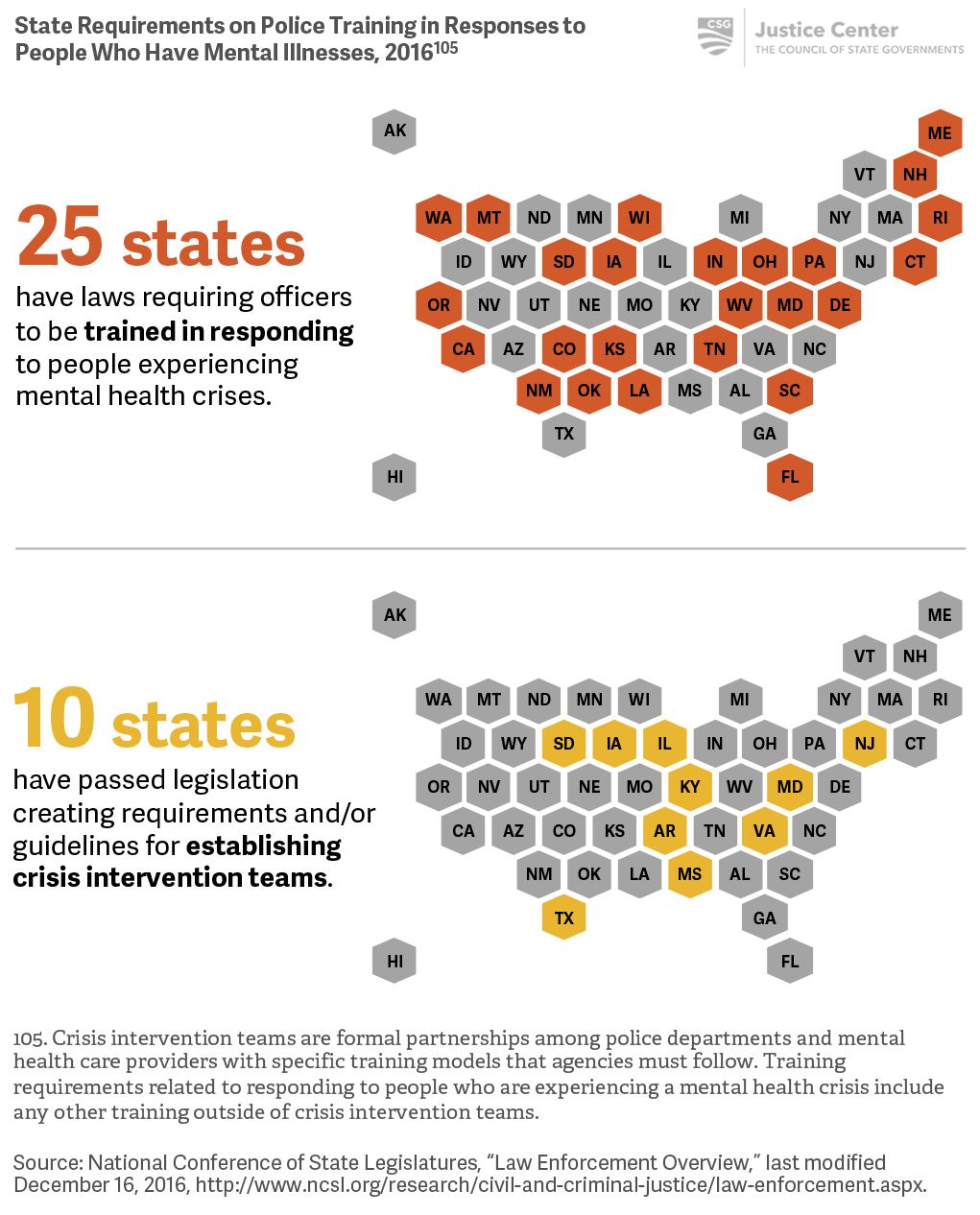

- Require behavioral health intervention training for law enforcement officers and assist local agencies in implementing best practices such as CIT models.

- See Case Study: Georgia develops statewide CIT curriculum

- See Case Study: Portland Maine Police Department improves responses to people who have mental illnesses

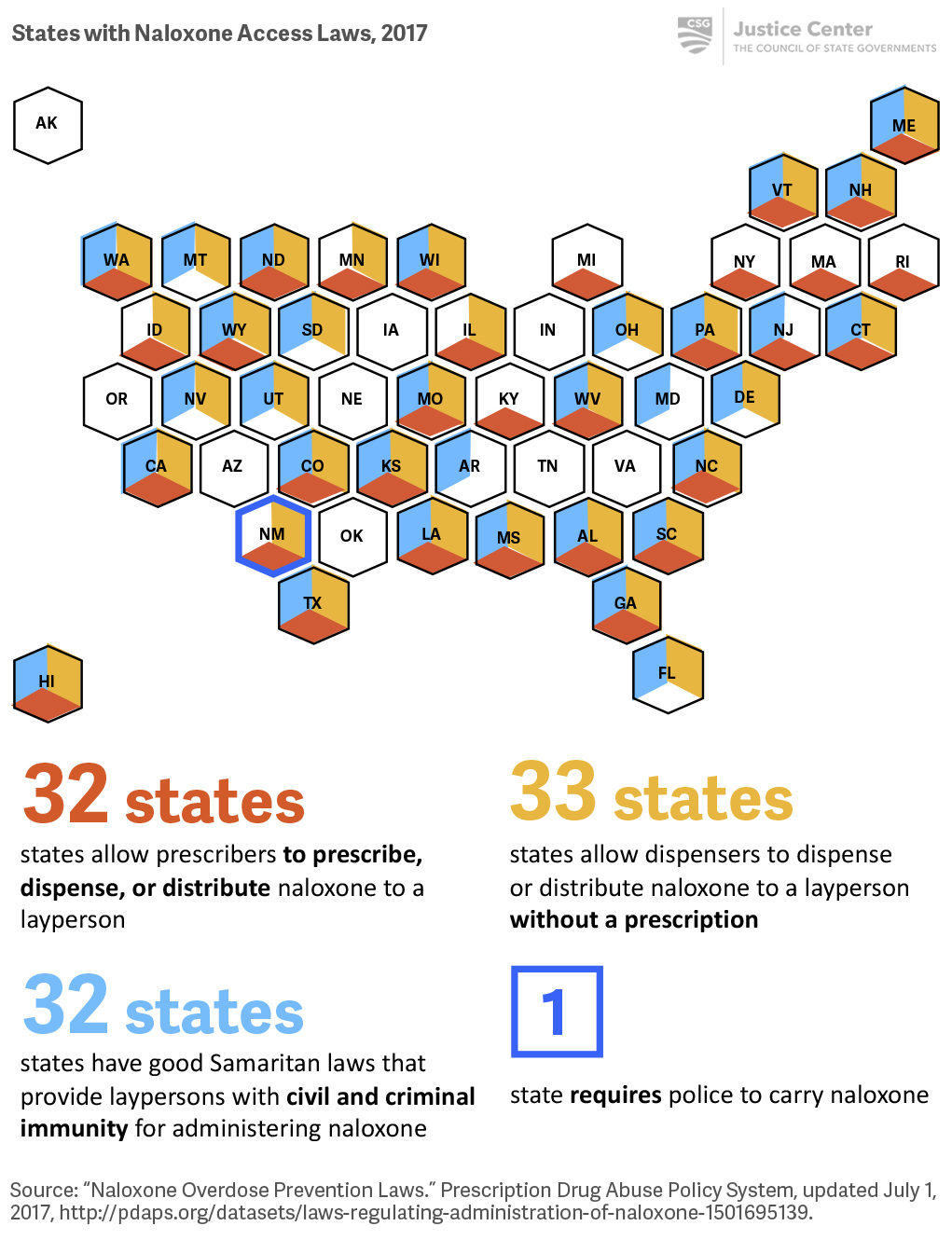

- Require training for police officers in opioid death prevention strategies, and provide state funding to support local jurisdictions in developing naloxone programs.

- See Case Study: New Mexico becomes the first state to require police use of naloxone

- See Case Study: Utah provides funding to law enforcement agencies for naloxone programs

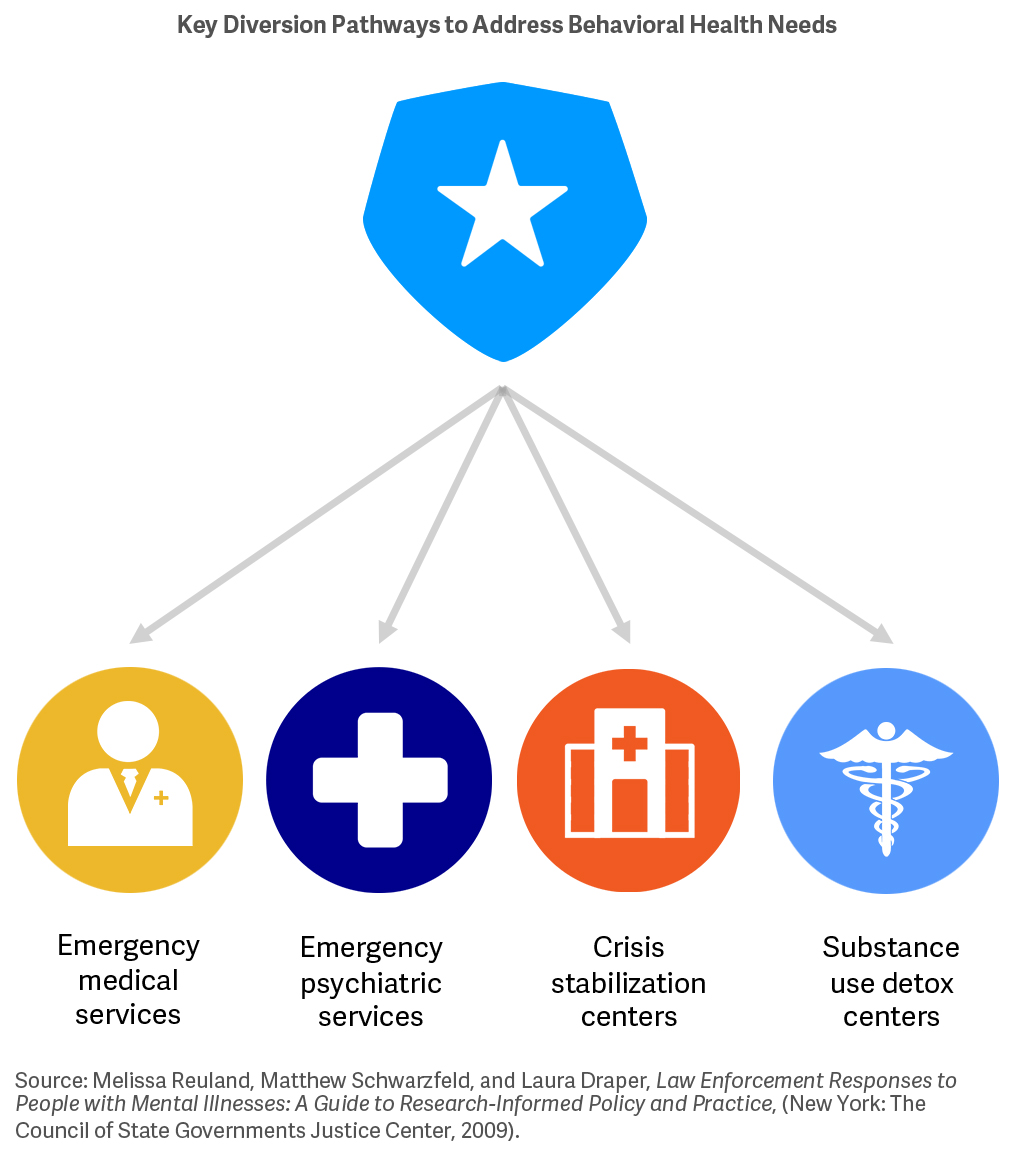

- Facilitate partnerships between state behavioral health agencies and local law enforcement agencies.

- See Case Study: Mental health/criminal justice partnerships in Oklahoma create statewide specialized response training

- Increase funding to state crime labs.

- Increase standards for training and resources for officer wellness.

- See Case Study: Wisconsin improves standards and training for officer wellness

Key questions to guide action

- What policies does your state have in place to ensure that police officers are adequately trained to interact with a person who is experiencing a mental health crisis?

- What training and tools do law enforcement agencies in your state use to help prevent opioid overdose deaths? How is the state supporting those efforts?

- How is your state facilitating partnerships between police, emergency services, and long-term care providers?

- How can your state improve the operations of publicly-funded crime labs?

- What can your state do to ensure adequate training and resources for law enforcement agencies to promote officer wellness?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

Some states support or require specialized training for police officers to improve interactions between officers and people experiencing mental health crises.

A number of states have passed laws to increase access to naloxone and/or remove barriers and liabilities for non-medical professionals, including law enforcement officers, in administering the drug to people experiencing an opioid overdose. However, only one state currently requires police to carry naloxone to treat overdoses.

Officers must be able to refer people experiencing mental health or overdose crises to community-based supports and services for appropriate ongoing care.

Most jurisdictions rely on state crime labs for forensic analysis, where there are backlogs that hinder law enforcement’s ability to investigate crimes.

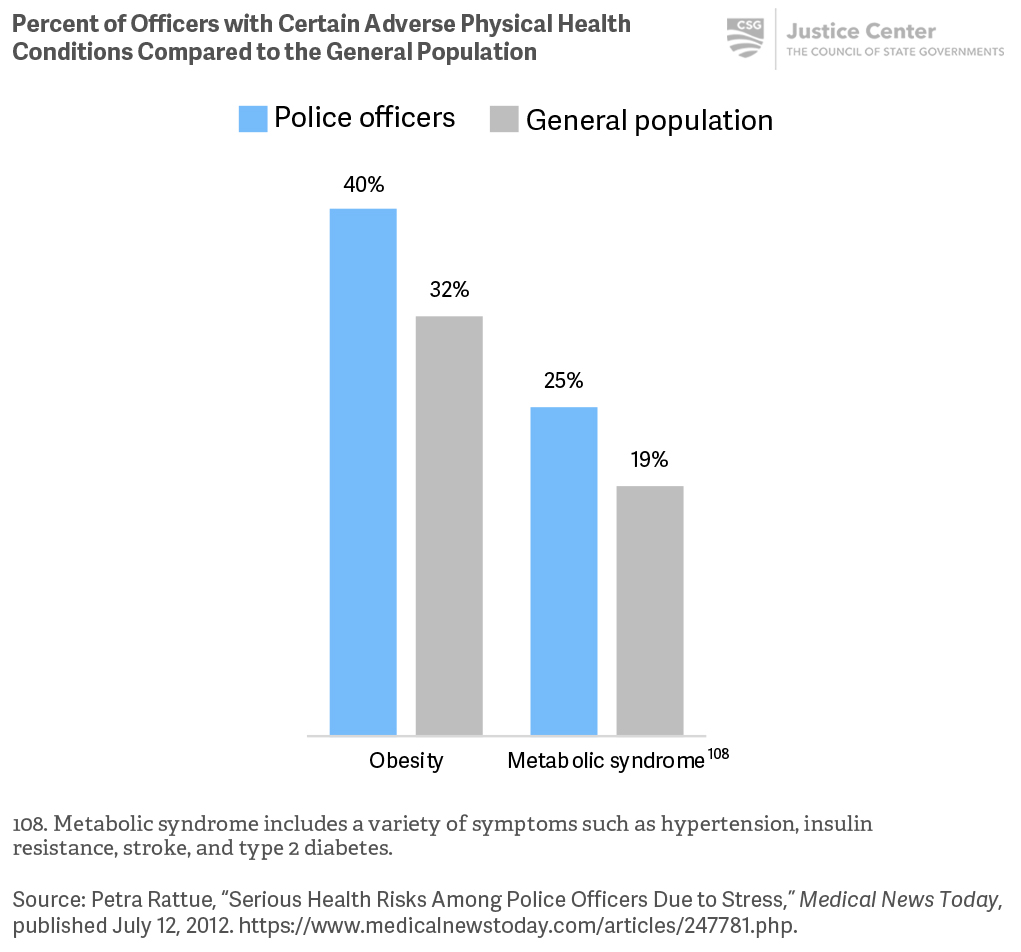

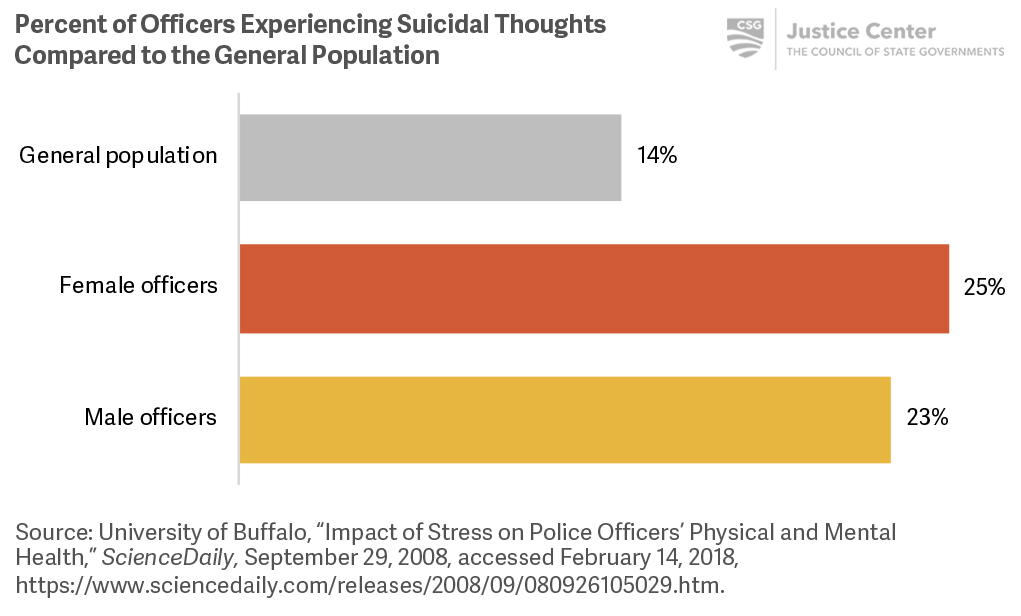

Police officers experience higher rates of obesity, PTSD, suicidal thoughts, troubled sleep, and other conditions than the general population. These physical and psychological health conditions adversely affect their quality of life and jeopardize public safety.

Additional Resources

Officer Wellness

Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA)—Officer safety programs for state, local, and tribal law enforcement officers and executives to reduce risk to officers and improve wellness. BJA has several robust programs targeted toward improving officer wellness:

- Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS Office)—A library of resources to help agencies better protect against incapacitating physical, mental, and emotional health problems and hazards of police work.

- Preventing Violence Against Law Enforcement and Ensuring Officer Resilience and Survivability (VALOR)—Comprehensive training effort that provides all levels of law enforcement with tools to help prevent violence against law enforcement officers and enhance officer safety, wellness, and resiliency.

Other programs include:

- The Center for Officer Safety and Wellness—A priority of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the center focuses on providing resources for all aspects of an officer’s safety, health, and wellness, both on and off the job.

- Destination Zero—National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund (NLEOMF) initiative to improve the safety and wellness of law enforcement officers.

Amy C. Watson and Anjali J. Fulambarker, “The Crisis Intervention Team Model of Police Response to Mental Health Crises: A Primer for Mental Health Practitioners,” Best Practices in Mental Health 8, no. 2 (2012): 71.

Alexander Y. Walley et al., “Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis,” The BMJ (2013): 346.

CSG Justice Center, Police-Mental Health Collaboration Programs: Checklist for Law Enforcement Leaders (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2016).

President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, Final Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2015).

Case Study

Georgia develops statewide CIT curriculum

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) developed a CIT training curriculum, with the help of National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Georgia’s executive board and staff from the Georgia Public Safety Training Center. Over the course of six months, GBI staff developed a 300-page curriculum that has been used in all CIT trainings since 2004. To develop the curriculum, GBI staff studied curricula used in Memphis, St. Louis, and Houston. Staff adapted modules they believed to have the greatest impact, and ensured that the instruction was consistent with Georgia state law. Content experts were identified to take the lead on developing specific modules. Once a draft curriculum was developed, it was reviewed and approved by an advisory board and pilot tested in several sites. A revised version was then approved by the Georgia Peace Officer Standards and Training Council (POST). GBI has since modified the curriculum for rural areas. GBI works with local police departments to provide a 40-hour basic CIT training for selected officers based on the curriculum the bureau developed.

For more information about the GBI’s efforts to promote CIT across the state, visit the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Case Study

Portland Maine Police Department improves responses to people who have mental illnesses

In 2010, the Portland Maine Police Department (PPD) was one of six law enforcement mental health learning sites initially chosen by The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center, with assistance from a team of national experts and the U.S. Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA). Located across the country, these learning sites represent a diverse cross-section of perspectives and program examples and are dedicated to helping other jurisdictions improve their responses to people with mental illnesses. Agencies are able to use the learning sites to reduce repeat encounters with law enforcement, reduce arrests, and make encounters with officers safer. Each site answers questions, hosts site visits, and develops materials for practitioners and community partners.

The PPD has developed innovative programs and collaborative partnerships to address increased calls for service involving people who have behavioral health issues. PPD began their efforts in 1996 with the creation of a police liaison position on mental health, and the department has since developed a Specialized Behavioral Health Response Program with trained officers who respond to often time-consuming, complex calls involving people who have mental illnesses.

PPD’s mental health liaison responds to calls alongside officers. In 2011, to offer more assistance, the PPD began collaborating with the University of Southern Maine Clinical Counseling Program to provide year-long internships for Master’s program participants interested in responding to calls for service with officers, conducting follow-ups, and making referrals to mental health providers. In 2015, the mental health unit was further expanded to include a substance use disorder liaison. And as of 2017, the PPD has a full-time behavioral health coordinator who collaborates with care providers to help people who have behavioral health needs, primarily by managing the co-responder teams and facilitating officer training.

The PPD has also worked with the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) Maine since 2001 to provide Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training to improve how officers respond to people experiencing a mental health crisis. Although initially a volunteer program, PPD now mandates that all officers complete the CIT training program.

In 2018, the CSG Justice Center chose four additional law enforcement mental health learning sites—Madison County (TN) Sheriff’s Office, Arlington (MA) Police Department, Jackson County (OH) Sheriff’s Office, and the Tucson (AZ) Police Department. The sites will provide resources for state and local law enforcement agencies that are developing or enhancing a Police-Mental Health Collaboration, including a Crisis Intervention Team, co-response team, or mobile crisis team. For additional information, see Law Enforcement/Mental Health Learning Sites.

Case Study

New Mexico becomes the first state to require police use of naloxone

In 2017, New Mexico became the first state to pass legislation requiring all local and state law enforcement officers to carry naloxone, a drug that can rapidly reverse an opioid overdose. The bipartisan legislation passed unanimously and was signed into law by Governor Susana Martinez on April 6, 2017.

In addition to equipping police with naloxone, the legislation requires federally-certified addiction treatment centers to provide patients with educational materials about how to respond to overdoses, two doses of naloxone, and a prescription for a refill. The law also requires jails and prisons to provide these naloxone supports when people at risk of overdose exit state or county facilities.

This is one of many measures New Mexico has implemented over the last decade to curb opioid overdose deaths including releasing people from legal liability when they assist in overdose situations, allowing pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription, and requiring all licensed clinicians to undergo extra training for prescribing opioid painkillers. The current legislation adds police officers to the growing list of professionals who have access to anti-overdose medication to save lives and increase recovery.

Case Study

Utah provides funding to law enforcement agencies for naloxone programs

In 2016, the Utah legislature passed a law creating the Opiate Overdose Outreach Pilot Program within the Utah Department of Health (UDOH). This pilot program, which launched in January 2017, aims to curb the state’s rising rate of overdose deaths by providing police departments, local health departments, and service providers with naloxone.

This pilot program is distinct from similar programs in other parts of the country in that the Utah legislature appropriated a quarter million dollars specifically for the purchase and distribution of naloxone kits. In the first half of 2017 alone, the pilot program enabled the UDOH to award 32 agencies, including 17 police departments, a total of about $236,000 to buy and distribute naloxone kits as well as to train people on how to use them. During that six-month period, more than 3,000 kits were purchased and nearly 2,000 were distributed, which resulted in 46 saved lives.

Case Study

Mental health/criminal justice partnerships in Oklahoma create statewide specialized response training

Local and state agencies in Oklahoma have established partnerships that aim to create and sustain more effective interactions among law enforcement, mental health care providers, and people with mental illnesses. Collaborations between the Oklahoma Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (ODMHSAS), the Oklahoma Association of Chiefs of Police, and local police departments have led to the formation of Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) and Corrections Crisis Response Teams (CCRT).

- The Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) program trains police responders to use crisis de-escalation strategies and to prioritize treatment over incarceration when appropriate. Since the beginning of this program in 2002, more than 1,200 officers have been trained across Oklahoma.

- Corrections Crisis Response Team (CCRT) is a program designed to improve interactions between correctional officers, supervision officers, and people in crisis who also have a mental illness.

Similarly, collaborations between the ODMHSAS and Oklahoma Department of Corrections (DOC) have led to the creation of Integrated Services Discharge Managers, Re-Entry Intensive Care Coordination Teams, and Co-occurring Treatment Specialists (COTS). Each of these programs connect people in DOC custody or those leaving correctional facilities with mental health or substance use treatment.

Case Study

Wisconsin improves standards and training for officer wellness

Under the direction of the state’s Attorney General, the Wisconsin Department of Justice (DOJ) improved standards and training in 2017 to support the health and safety of law enforcement officers across the state. The DOJ has focused its efforts on three key areas: (1) suicide prevention, (2) physical wellness, and (3) stress management. These efforts include:

- Adding 4 hours of suicide prevention training to the recruit academy curriculum

- Adding 34 hours of physical fitness to the recruit academy training[104]

- Adding 8 hours of training for new recruits on living a healthy lifestyle, stress management, maintaining healthy relationships, and maintaining financial stability

- Incorporating wellness training into all new training programs for chiefs, sheriffs, and jail administrators

Wisconsin DOJ is considered a national leader in officer wellness; in 2017, the agency was a finalist for the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance’s National Officer Safety and Wellness Awards.

[104] Suicide prevention training includes a wide range of topics, such as how to manage stress and maintain a healthy lifestyle to deter suicidal thoughts or how to recognize if a colleague may be considering suicide.