Part 3, Strategy 2

Action Item 2: Promote success on supervision and use proportionate responses to respond to violations.

Why it matters

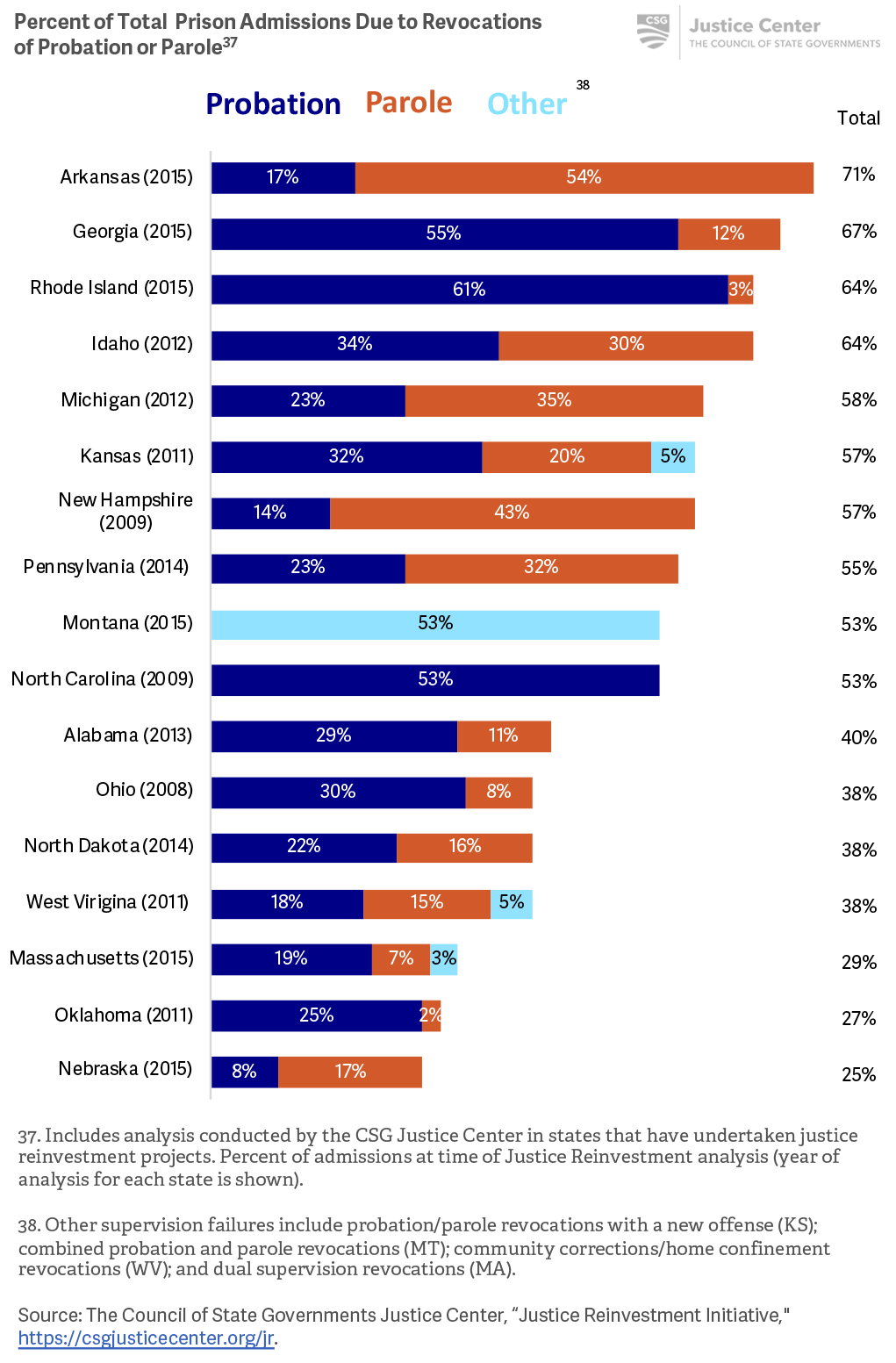

Every year, people failing on supervision account for a large portion of admissions to jails and prisons and stay for weeks, months, or even years at a time creating a huge expense for counties and states without necessarily increasing public safety. Some states have found that prison admissions due to people failing on supervision ranged from 25 percent of total admissions to as much as 71 percent.[29] In each of these states, a significant portion of people entering prison had violated conditions of supervision or committed offenses that otherwise would not have been serious enough to warrant a prison sentence. Given the burden of incarceration on state and local budgets, the negative effect even short periods of incarceration can have on people, and the research that shows that community-based sanctions can be as effective as sanctions to incarceration, jurisdictions across the country are beginning to develop policy changes to use resources more effectively when responding to supervision violations.[30]

To reduce the likelihood of reoffending and facilitate behavior change, supervision agencies need to incorporate a range of sanctions to respond to negative behavior and incentives to recognize and reward prosocial behavior. Incentives can range from verbal praise to reduced reporting conditions or early discharge from supervision. Sanctions vary depending on the severity of the violation and can range from a verbal reprimand to increased reporting requirements or spending time in jail or prison.

Research indicates that reinforcements for positive behavior are a better motivator for changing behavior than sanctions for poor behavior alone, and reinforcements should be used at least four times as often as sanctions in order to enhance individual motivation and encourage the continuation of prosocial behavior.[31] Best practices call for sanctions and incentives that are swift, certain, and proportionate to supervision behavior so that people on supervision see the response as a direct consequence of their behavior.[32]

To increase fairness of responses and consistency across staff, supervision agencies in some states are developing structured approaches to guide supervision officers in how they respond to behavior on supervision. One way supervision agencies can adopt a structured approach is by developing response matrices containing a continuum of sanctions and incentives that address behaviors, link people to community resources to address criminogenic needs, and are responsive to a person’s risk of reoffending.

A growing number of states are also setting limits on the amount of time someone can be incarcerated in jail or prison for violating conditions of supervision without committing a new crime. These policies allow states to prioritize incarceration for people convicted of serious and violent offenses.

What it looks like

- Require supervision agencies to employ a range of incentives and sanctions to respond to behavior on supervision in a timely manner.

- Promote using a greater proportion of incentives than sanctions to encourage behavior change on supervision.

- Require supervision agencies to establish a structured decision-making framework for responding to behavior on supervision.

- See Case Study: Idaho and Nebraska establish matrices to respond to supervision violations

- Require supervision agencies to respond to probation and parole violations with more effective and less costly sanctions.

- See Case Study: States reduce use of incarceration for technical violations

- See Case Study: Michigan provides programming and training to people who have violated probation

Key questions to guide action

- What percentage of people admitted to prison in your state are revoked from probation or parole and for what reasons? How long do they stay?

- What incentives and sanctions can supervision officers use currently and how are they employed? What improvements are necessary to ensure consistency in responding?

- Do supervision agencies track the effectiveness of responses and publish results?

- Does your state set limits on how long people can be incarcerated for violating supervision conditions? What updates to these policies are needed, if any?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

Analysis conducted during Justice Reinvestment projects in 17 states revealed that people revoked from probation and parole made up a significant portion of prison admissions.

CSG Justice Center analysis of states the Justice Center assisted in pursuing a Justice Reinvestment approach between 2008 and 2015. Percent of admissions is at time of Justice Reinvestment analysis, prior to enacting policy changes as a result of Justice Reinvestment approach.

Laura and John Arnold Foundation, “Research Summary: Pretrial Criminal Justice Research” (New York, NY: Laura and John Arnold Foundation, 2013); Eric Wodahl, John Boman, and Brett Garland, “Responding to Probation and Parole Violations: Are Jail Sanctions More Effective Than Community-Based Graduated Sanctions?” Journal of Criminal Justice 43, (2015): 242–250; Paul Gendreau, Francis Cullen, and Claire Goggin, “The Effects of Prison Sentences on Recidivism” (Canada: Ministry of the Solicitor General, 1999).

Paul Gendreau and Claire Goggin, “Correctional Treatment: Accomplishments and Realities,” in Correctional Counseling and Rehabilitation, ed. Patricia Van Voorhis, Michael Braswell, and David Lester. (Cincinnati, OH: Anderson, 1997), 271–280; Eric Wodahl et al., “Utilizing Behavioral Interventions to Improve Supervision Outcomes in Community-Based Corrections,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 38, no. 4 (2011): 386-405.

Daniel Nagin, Francis Cullen, and Cheryl Lero Johnson, “Imprisonment and Reoffending,” Crime and Justice 38, no. 1 (2009): 115–200.

Case Study

Idaho and Nebraska establish matrices to respond to behavior on supervision

To ensure that supervision agencies use a structured approach to respond to supervision violations and encourage behavior change through the use of incentives, Idaho and Nebraska both established in statute through the Justice Reinvestment process that supervision agencies in the state must create matrices to guide responses to behavior on supervision.

In 2014, Idaho enacted Justice Reinvestment legislation that included a provision for probation and parole agencies to implement an evidence-based behavior response matrix, which gives supervision officers a standardized tool to address positive and negative behaviors swiftly and certainly. Probation and parole staff developed and piloted a response matrix, which included both incentives and sanctions. Staff from The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center held focus groups with probation and parole staff and solicited feedback from stakeholders in the pilot district before rolling out the response matrix statewide. An interagency workgroup, which included representatives from the parole commission, department of corrections, judges, prosecutors, and supervision staff, approved use of the matrix across the state. In addition, the workgroup developed a sustainability plan and identified metrics to monitor the application and quality of the response matrix’s use across the state.

Before fully implementing the tool, Idaho supervision officers relied heavily on sanctions and used few incentives to change behavior. By early 2018, probation and parole officers had increased their use of incentives. Between 2015 and 2018, the ratio of rewards to sanctions changed from one reward for every 5.7 sanctions to one reward for every 1.3 sanctions.[33] Idaho is continuing to evaluate how staff use risk and needs results along LSI-R domains to inform their use of sanctions and incentives, and aims to eventually have supervision officers employ four incentives for every sanction.[34]

In 2015, Nebraska enacted Justice Reinvestment legislation, which required the Division of Parole Supervision to develop an incentive and sanction matrix to promote positive behavior change through the use of incentives and hold people accountable for violations with a continuum of responses, including non-custodial and custodial options. After developing the matrix, the Division of Parole Supervision purchased software that generates automated responses based on the matrix and collects data to measure how staff utilize the incentives and sanctions and whether people on parole changed their behavior as a result. The Division of Parole Supervision uses the data from the software to assess how often officers use incentives and sanctions and determine if additional training is needed.

[33] Correspondence between CSG Justice Center staff and Idaho DOC staff, March 2018.

[34] Ibid. The Level of Service Inventory–Revised (LSI-R) is an actuarial risk and needs assessment tool designed to classify a person’s risk of reoffending as well as to identify their particular criminogenic needs.

Case Study

States reduce use of incarceration for technical violations

Across the country, states such as Hawaii, Mississippi, Utah, and Washington have established policies imposing caps on the period of time people can be incarcerated for violating conditions of supervision. The length of time a person can be incarcerated and the reasons they go to jail or prison vary by state. As states transition from using lengthy sanctions to shorter sanctions to respond to supervision violations, they are able to prioritize costly prison space for people convicted of the most serious and violent offenses.

For example, in 2007, Louisiana lawmakers unanimously approved legislation that caps incarceration time in jail or prison at 90 days for people on probation or parole who are initially convicted of nonviolent offenses and are revoked for the first time for violating the conditions of supervision. An evaluation of the policy concluded that between 2007 and 2012,

- The average length of incarceration for first-time technical revocations in Louisiana fell by 281 days, or more than 9 months;

- The number of people on supervision returned to custody for new crimes declined from 7.9 percent to 6.2 percent, a 22-percent decrease; and

- State taxpayers saved approximately $17.6 million in annual corrections costs as jails and prisons used about 2,034 fewer jail and prison beds annually.[35]

[35] The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Reducing Incarceration for Technical Violations in Louisiana: Evaluation of Revocation Cap Shows Cost Savings, Less Crime,” (Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2014).

Case Study

Michigan provides programming and training to people who have violated probation

In an effort to reduce the number of people entering prison due to probation violations and to provide people who repeatedly violate probation with intensive programming, the Michigan Department of Corrections launched the Wayne Residential Alternative to Prison (WRAP) pilot program in 2016. Instead of revoking people to prison for long periods of time, WRAP gives judges the ability to sentence people on probation to four to six months of confinement at the Detroit Reentry Center where they receive intensive programming.

WRAP targets people who have committed a new felony or misdemeanor and who are assessed as being at a moderate to high risk of reoffending. Judges refer people to the program via a court order, and probation staff may also recommend that people participate. WRAP provides cognitive behavioral programming designed to affect criminal thinking and attitudes, and vocational training that gives people the opportunity to earn technical certifications.[36]

[36] Michigan Department of Corrections, “WRAP Probation Violator Diversion Program” (Corrections Subcommittee Hearing Testimony, March 10, 2016).