Part 1, Strategy 4

Action Item 2: Advance violent crime reduction efforts by improving trust and cooperation between communities and police.

Why it matters

A pervasive and persistent myth in American communities is that public safety and crime reduction is the sole purview of law enforcement agencies. In reality, law enforcement officers are just one component, albeit an important one, in improving public safety and reducing crime. The community has an equally important role to play in creating and maintaining neighborhood safety. Ideally, law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve work together to achieve mutual public safety goals.

A lack of trust between the community and law enforcement can make it difficult to solve violent crimes, a process that relies heavily on community members’ knowledge of events in their own neighborhoods and the community’s willingness to identify perpetrators and help deter future crime. When there is a lack of cooperation from community members, police officers lack the basic information necessary to carry out the tailored crime-prevention and problem-solving strategies that make community-based initiatives successful in reducing violent crime.[93]

While a large number of law enforcement agencies are implementing aspects of community policing and geographic-based policing, there is still significant work to do to improve trust and collaboration between communities and the police. States can play an integral role in increasing trust through proactive public policy and by supporting system-wide tactics and tools that facilitate positive community relationships.

What it looks like

- Create accountability for law enforcement agencies in establishing and maintaining positive relationships with the community.

- See Case Study: Washington becomes the first state to require formal review of policing practices

- Improve training on how to implement community policing with fidelity.

- See Case Study: New Haven Police Department implements community-based policing

- Provide resources to smaller jurisdictions to help increase the use of policing strategies that build trust.

- See Case Study: Grant and outreach workers help bring community policing to rural Kentucky

- Support local law enforcement agencies in surveying the community to determine perceptions of police and levels of trust.

- See Case Study: Seattle Police Department uses community surveys to track and improve trust

Key questions to guide action

- What data do law enforcement agencies in your state collect to ensure police accountability and transparency?

- How can your state assist local law enforcement in strengthening communities’ trust?

- What more can be done in your state to incentivize collaboration between law enforcement and relevant stakeholders at both the state and local level?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

Effective crime-fighting strategies require trust and collaboration between police and the communities they serve, which can be fostered by a variety of evidence-based strategies.

Community Policing

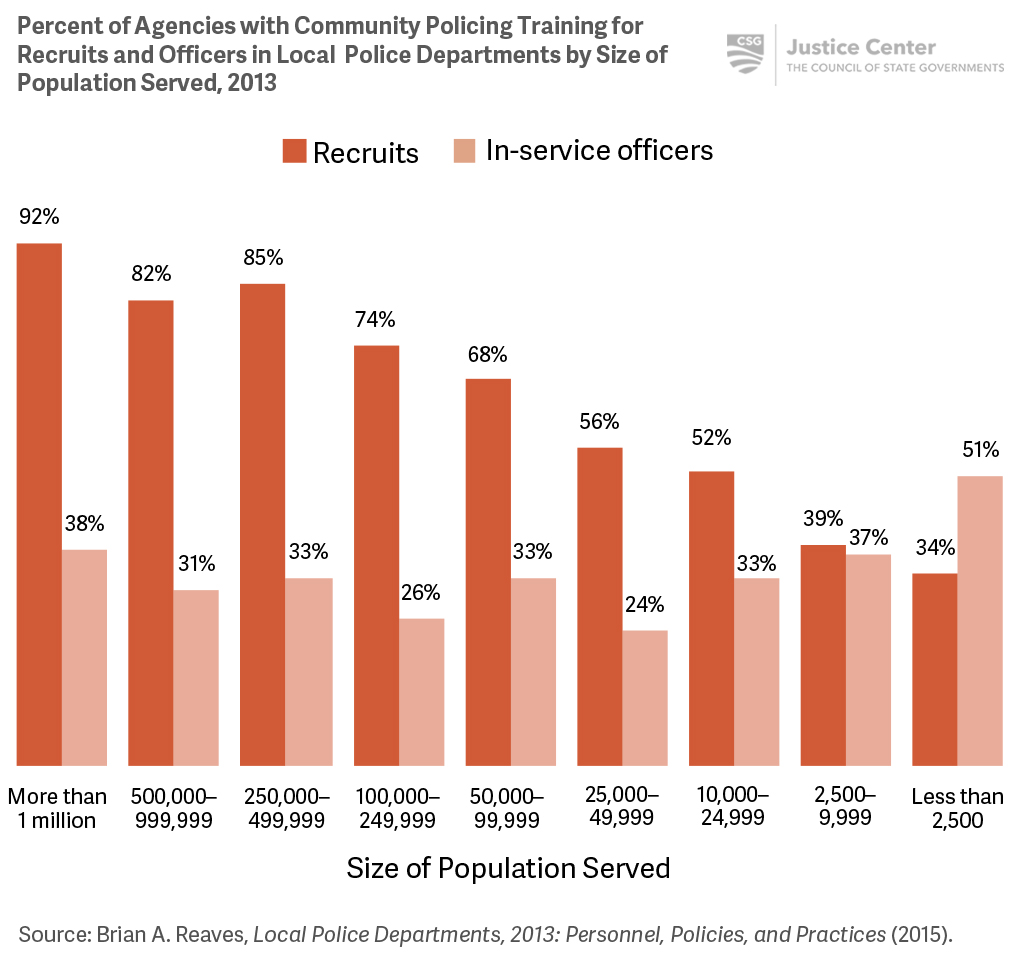

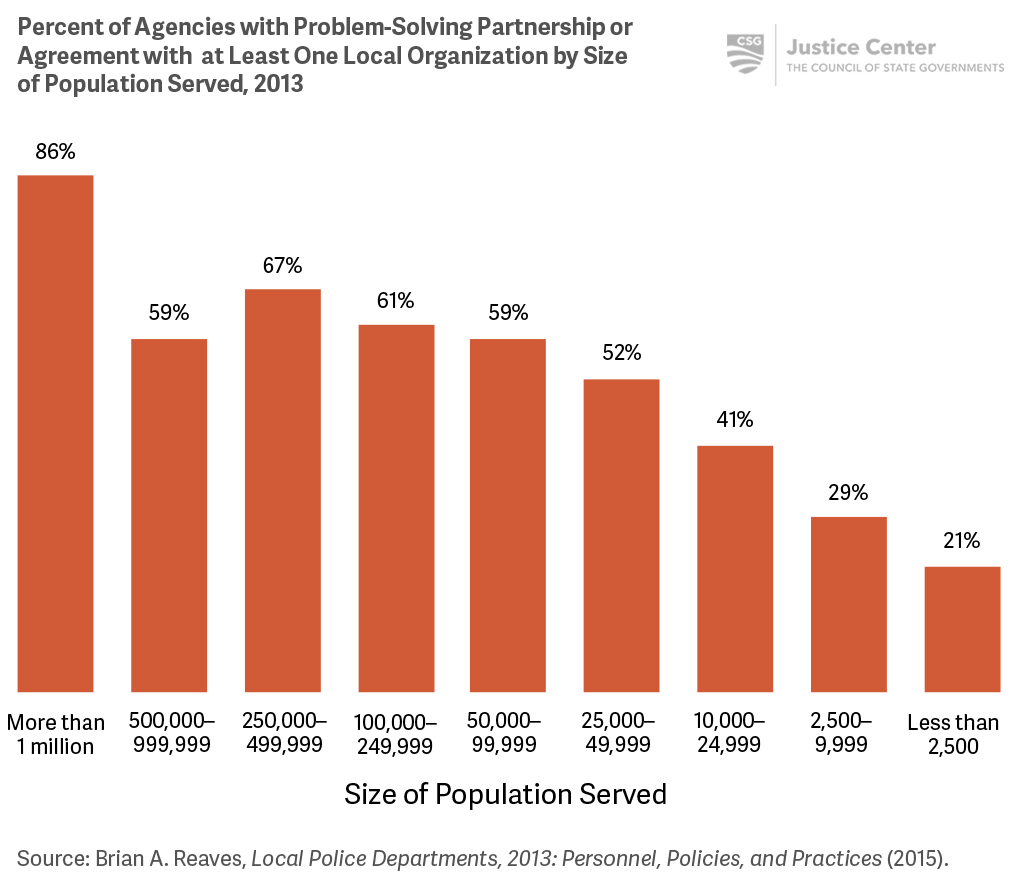

Community policing is a systematic, collaborative approach to public safety that encourages law enforcement agencies to partner with community groups, nonprofits and service providers, businesses, media, and other government agencies to jointly and proactively solve community problems.[97] Community policing has been found to have significant positive benefits related to community satisfaction and perceptions of police legitimacy.[98] While most agencies now train and use some community policing components, few have active problem-solving partnerships with the community.

Geographic-based Policing

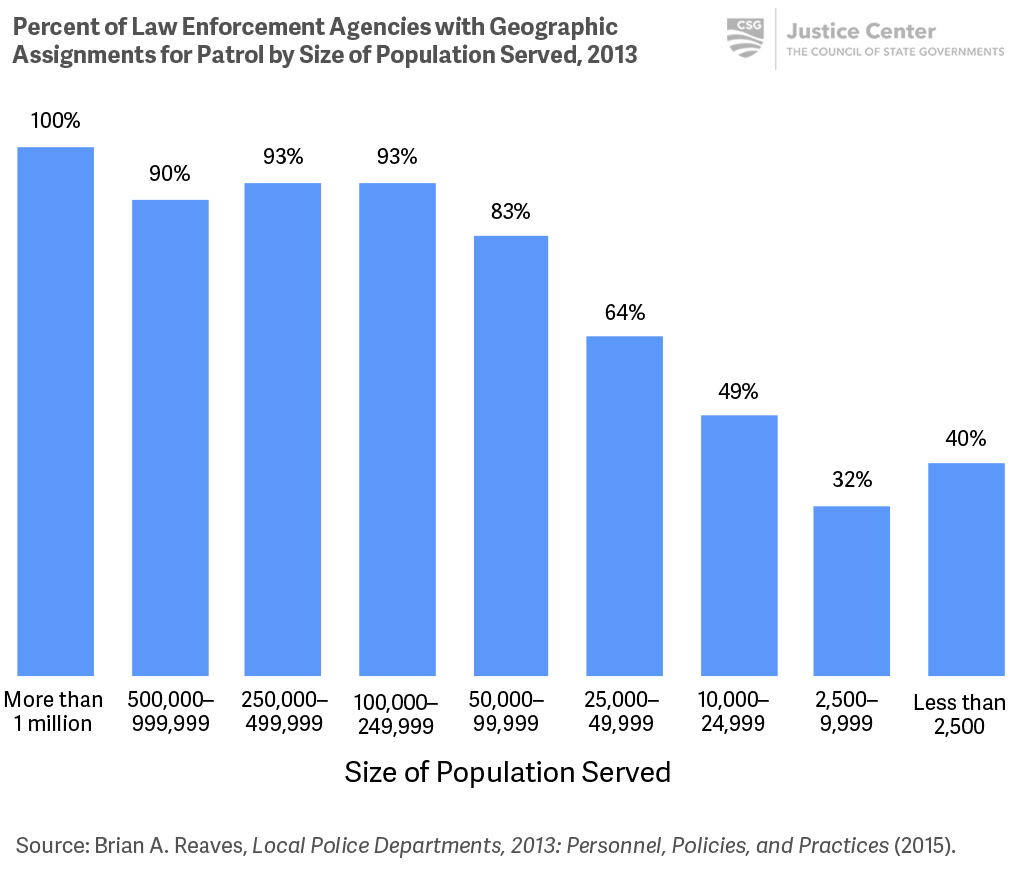

The geographic assignment of police officers involves establishing a regular beat for each officer so that they return to the same neighborhood at the same time of day over time. This strategy allows officers to become familiar with the area they police and the people who live there, and helps the community know and trust individual law enforcement officers. This familiarity can help to improve the community’s perception of police, satisfaction with police performance, and create a sense of partnership in preserving public safety.

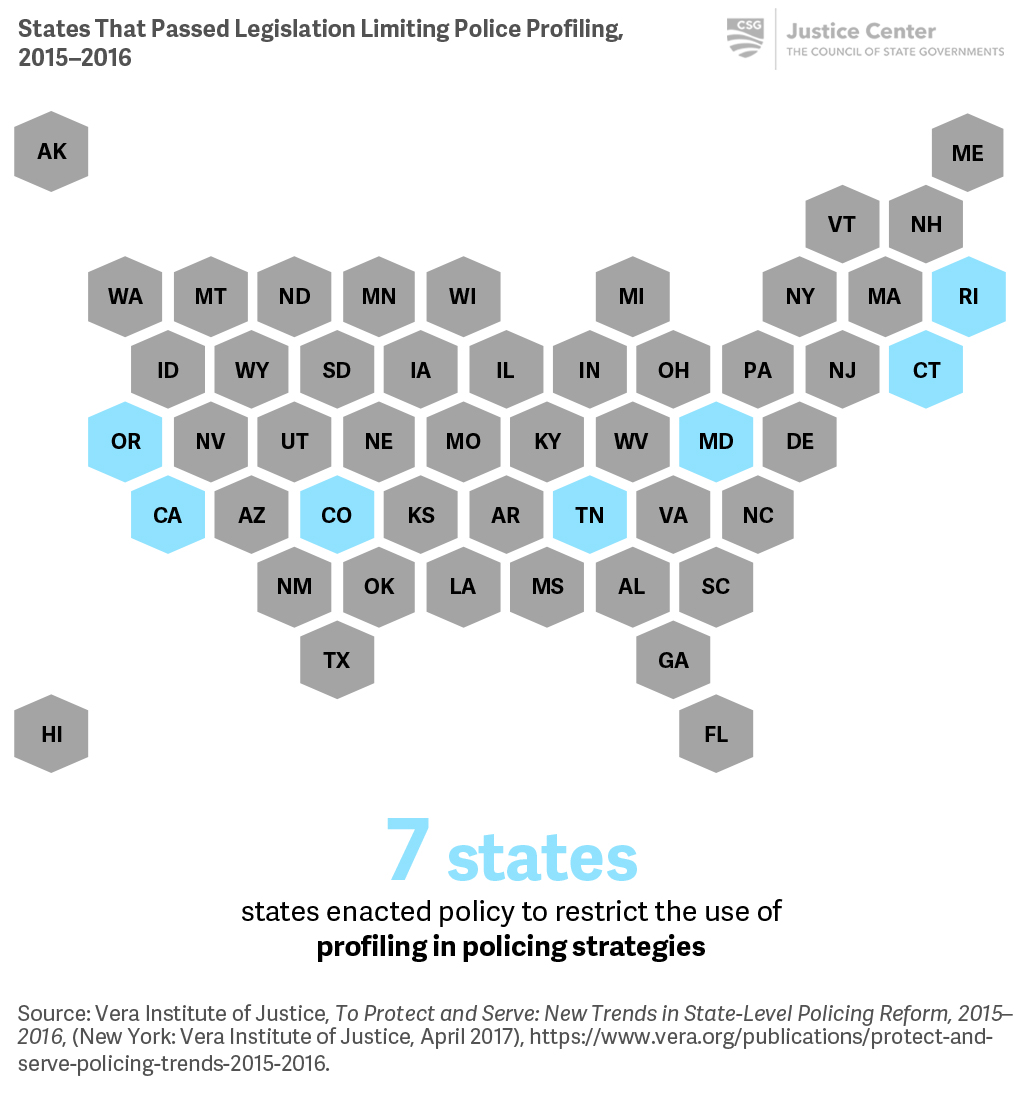

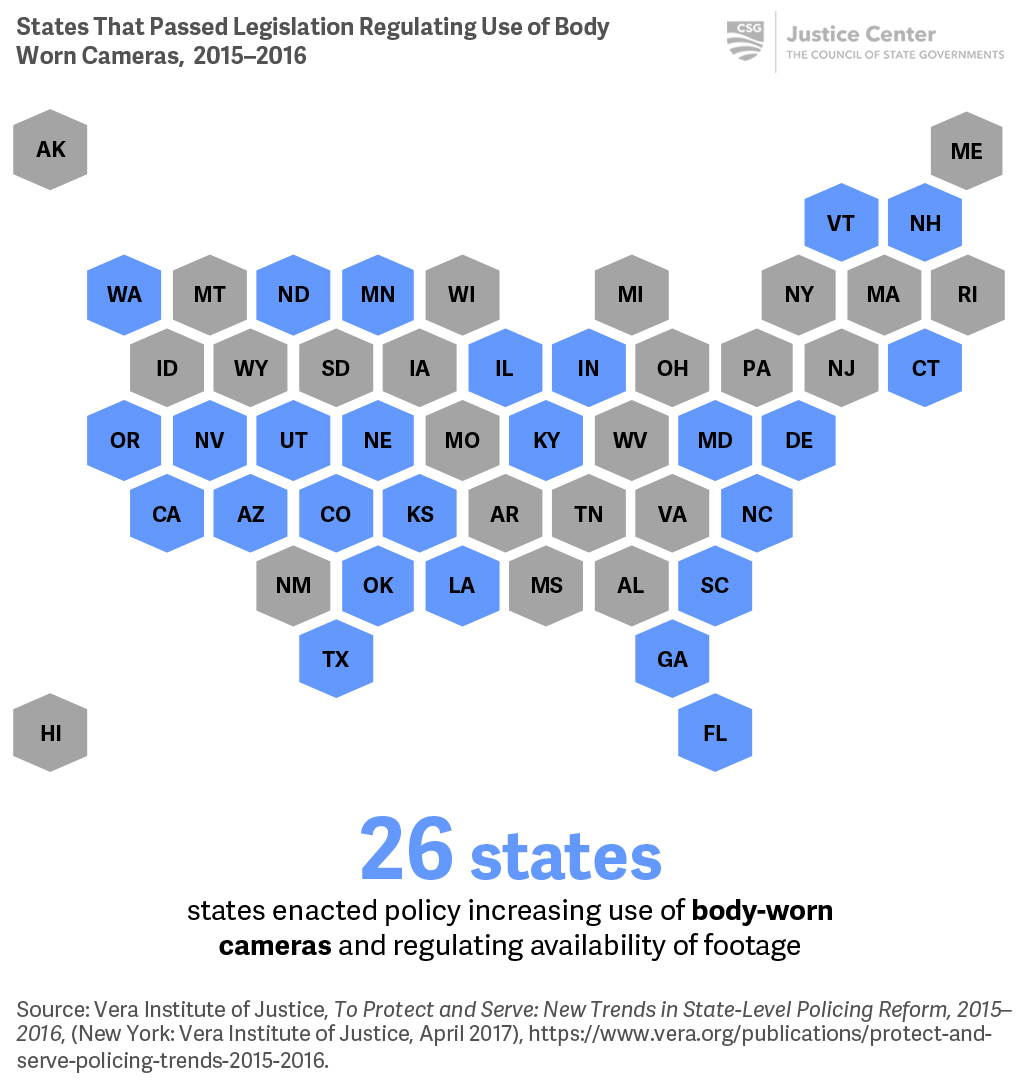

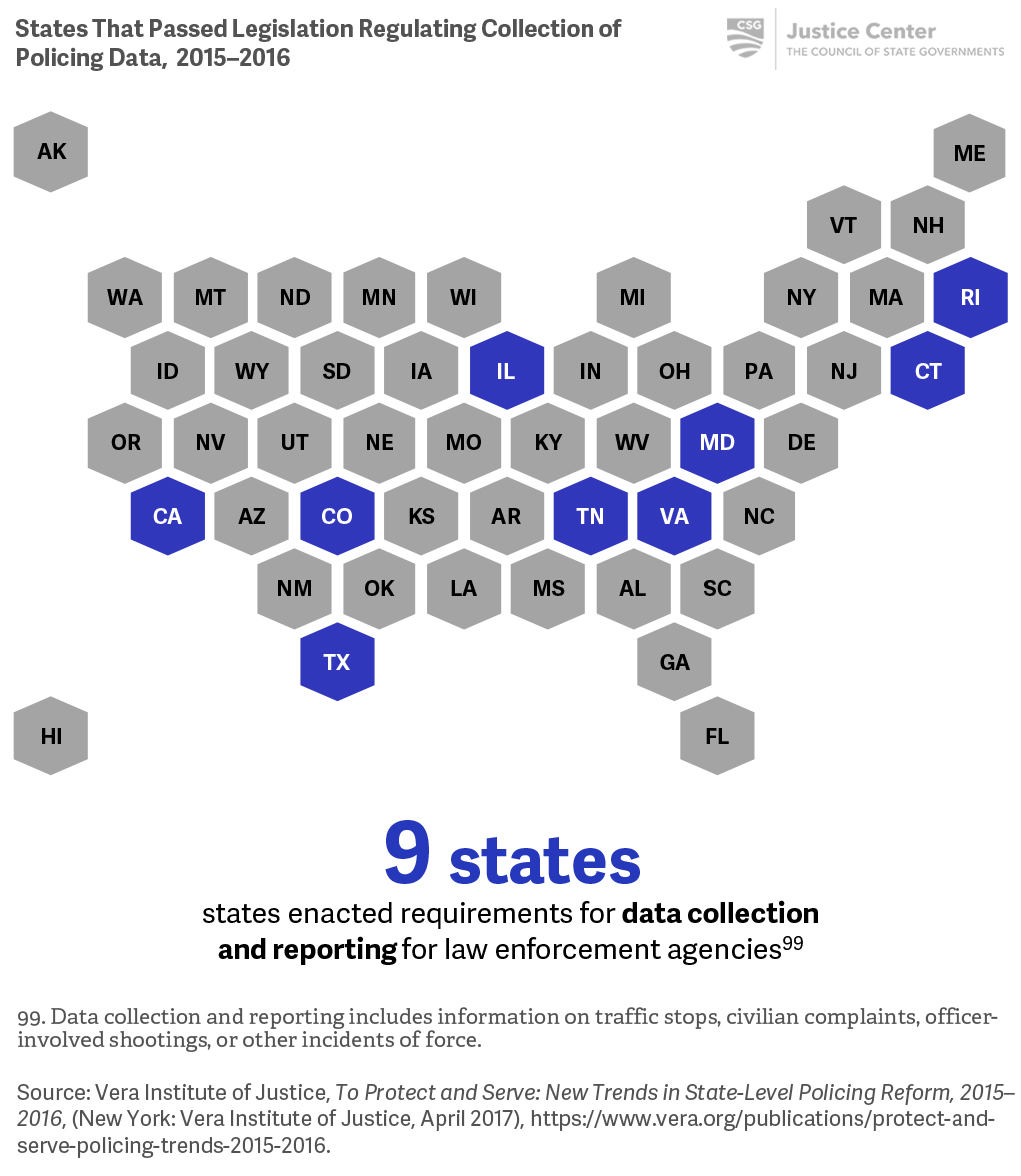

States are helping encourage community trust in police by improving data transparency, increasing use of body-worn cameras for better oversight of police activities, and restricting use of profiling in policing strategies.

Additional Resources

Building Community Trust

- International Association of Chiefs of Police—Provides model policies, educational resources, reports, and articles about building trust and legitimacy.

- Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS), U.S. Department of Justice—Provides training on procedural justice, bias reduction, and racial reconciliation to promote an environment in which effective partnerships between the police and citizens can flourish.

- Blue Courage—Innovative training on integrity, courage, and character for law enforcement officers of all ranks.

Robert Wasserman and Zachary Ginsburg, Building Relationships of Trust: Moving to Implementation (Tallahassee, FL: Institute for Intergovernmental Research, 2014).

Community policing and geographic assignment of officers have been proven to build trust between police officers and the communities they serve. Although there is only limited, but promising, evidence showing that these strategies can directly reduce crime, research does show that improved trust between communities and law enforcement contributes to the effectiveness of strategies like problem-oriented or hot-spot policing, which can help reduce crime.

This data includes a nationally representative sample of state and local law enforcement agencies surveyed by the Bureau of Justice Assistance through the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS) Survey.

Case Study

Washington becomes the first state to require formal review of policing practices

Across the country, community trust in police is significantly eroded by incidents involving excessive use of force and officer-involved civilian deaths. In 2016, Washington became the first state to establish an official review process to evaluate the use of deadly force by police officers to help improve community trust.

The legislature established a task force composed of a diverse group of state and local law enforcement agency representatives; prosecutors; defense attorneys; representatives from community organizations; representatives from the state Commissions on African-American, Pacific Asian, Indian, and Hispanic Affairs; and others. The task force is charged with reviewing the tools that police can use as alternatives to deadly force; reviewing laws, practices, and trainings on use of deadly force across the country; creating recommendations for best practices in reducing violent interactions between police and the community; and publicly reporting findings and recommendations.

Staff from Senate Committee Services and the House Office of Program Research were designated to support the work of the task force. The task force submitted its final report in December 2016, and the following provisions were signed into law and became effective on June 8, 2018:

- Adopts a “good faith” standard for law enforcement officer use of deadly force.

- Requires law enforcement officers in the state to:

- Receive ongoing violence de-escalation training to practice their skills, update their knowledge and training, and learn about new legal requirements and violence de-escalation strategies.

- Receive ongoing mental health training and periodically receive continuing mental health training to update their knowledge about mental health issues and associated legal requirements and to update and practice skills for interacting with people who have mental health issues.

- Requires the criminal justice training commission, when developing curricula, to consider inclusion of alternatives to the use of physical or deadly force so that de-escalation tactics and less lethal alternatives are part of the decision-making process regarding use of deadly force.

- Requires an independent investigation to be completed to inform a determination of whether the use of deadly force met the good faith standard and satisfied other applicable laws and policies.

For a full list of findings and recommendations, see Washington State Joint Legislative Task Force on the Use of Deadly Force in Community Policing Final Report.

Case Study

New Haven Police Department implements community-based policing

In 2011, the New Haven Police Department (NHPD) introduced community-based policing as a cornerstone of the city’s revitalization strategy.[94] To be successful, this style of policing depends on building trust and establishing relationships between police and the community they serve.

As part of its trust-building strategy, the NHPD requires all new police academy graduates and more than one-third of officers on evening shifts to patrol their assigned community on foot, or “walk a beat,” to increase face-time within the community. From 2012, when a significant portion of its officers were assigned to foot-patrol duty, to 2015, the number of homicides, robberies, motor-vehicle thefts and other types of serious crime in New Haven have fallen approximately 30 percent.[95]

In 2014, the MetLife Foundation and Local Initiatives Support Corporation recognized the effects of community-based policing efforts in New Haven. The NHPD along with its community partners received awards for Community and Police Partnerships and Neighborhood Revitalization.[96] Recognizing the impact that community-based policing is having in New Haven, Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy and The U.S. Conference of Mayors is calling for widespread adoption of the concept.

To learn more, see Neighborhood Housing Services of New Haven.

[94] “Community-Based Policing,” Neighborhood Housing Services of New Haven, accessed March 1, 2018, http://www.nhsofnewhaven.org/cbo/community-resources/community-based-policing.

[95] Gary Fields and John Emshwiller, “Putting Police Officers Back on the Beat,” Wall Street Journal, March 12, 2015, accessed March 1, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/putting-police-officers-back-on-the-beat-1426201176.

[96] Ibid.

Case Study

Grant and outreach workers help bring community policing to rural Kentucky

In 2015, Berea, Kentucky received support from the Innovations in Community Based Crime Reduction (CBCR) Program—administered by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance—to implement community policing strategies in rural Appalachia.

Berea had experienced a spike in youth drug crime and was facing significant challenges combating the problem across a large, but sparsely populated, geographic area. CBCR brought community organizations, social services, churches, and others together with the police to assess options for addressing the problem.

Employing traditional elements of community policing, Berea area residents and local police set about making hot spots for drug use less favorable for crime. Churches provided transportation services for youth to activities in more populated parts of the jurisdiction, other organizations started a youth wilderness camp to encourage positive interactions in known drug hot spots, and groups such as the Boys and Girls club expanded programming in these areas.

The additional resources provided by CBCR allowed the community to work with law enforcement to improve community safety. To learn more, see CBCR Site Features: Berea, KY.

Case Study

Seattle Police Department uses community surveys to track and improve trust

After a number of highly publicized incidents involving police use of force and racial profiling, the Seattle Police Department (SPD) entered a consent decree with the U.S. Justice Department. As part of the decree, SPD was required to use a scientific poll to measure changes in the community’s perceptions of SPD interactions with the public. The poll was conducted in 2013, 2015, and 2016, and sought to measure

- The frequency of certain events, such as use of excessive force or discriminatory policing;

- Public perceptions of the frequency of those events; and

- Public perception of how SPD treats people of varying racial and socioeconomic backgrounds.

The 2013 poll showed that 60 percent of respondents approved of the SPD, with lower approval ratings among African Americans and Latinos (49 percent and 54 percent, respectively) than whites and Asian Americans (60 percent and 67 percent, respectively). To strengthen performance, SPD reduced its officer-to-supervisor ratio to provide better day-to-day guidance of policing strategies, improve oversight of investigations and reviews of use of force, and ensure the quality of public service. SPD also altered the boundaries of traditional police beats to improve interactions between officers and the community.

During the years of study, perceptions of SPD’s performance improved significantly, moving from 60 percent job approval in 2013 to 72 percent in 2016. Public perception improved most notably among Latinos and African Americans. The poll also showed declines in experiences of excessive force and perceptions of the frequency of excessive force incidents during this period.

While perceptions of the frequency of racial profiling declined, the polling data showed that African Americans and Latinos were stopped by police for traffic-related or other issues significantly more than white people. However, the overall approval rating of police behavior during those stops has improved.

The most recent poll also revealed that the number of Asian Americans who reported an experience of racial profiling is at an all-time high, as are Asian-American perceptions of the frequency of racial profiling events. These data points are helping to guide SPD in making additional improvements.