Part 2, Strategy 4

Action Item 3: Reduce barriers to employment.

Why it matters

People returning to the community from incarceration struggle to find and keep a job for a variety of reasons, including minimal work experience, limited or diminished job skills, employers’ reluctance to hire, lack of state identification, inaccurate or incomplete criminal records, and the nearly 30,000 distinct job-related barriers to employment for people with criminal records that are contained within statutory and regulatory codes across the country.[43] Job applicants of color—particularly black men—who have a criminal record are the least likely to find employment after conviction or incarceration.[44] For example, one study found that 17 percent of white applicants with a criminal record receive callbacks from potential employers as compared to only 5 percent of black applicants.[45]

In addition to the negative effects on people and their families, these barriers have a significant impact on the overall economy. The economy loses approximately $78–87 billion annually due to people with criminal records being unemployed or underemployed.[46]

State and local leaders and corrections and workforce development professionals can engage the business community to understand and address the challenges associated with creating employment opportunities for people with criminal records. These conversations are necessary to build consensus and understanding about how government policies and local regulations can affect efforts to improve employment outcomes for people with criminal records. In addition, policymakers can identify the state-regulated occupational licensing restrictions that prevent people with criminal records from securing an occupational license and lift those restrictions when appropriate.

Research shows that after about seven years, a person’s criminal record no longer predicts the likelihood of future criminal behavior.[47] Yet employers often consider very old criminal records to be a reason to deny someone employment. Further, criminal background checks can produce incomplete or inaccurate information, which can prevent people from receiving employment offers or lead to their termination. Criminal record sealing and expungement—or record clearance—aims to address the absence of qualified workers due to criminal records to meet the demand of companies. Fair hiring policies typically delay consideration of a criminal record until later in the hiring process so that people with criminal records have a chance of becoming employed.

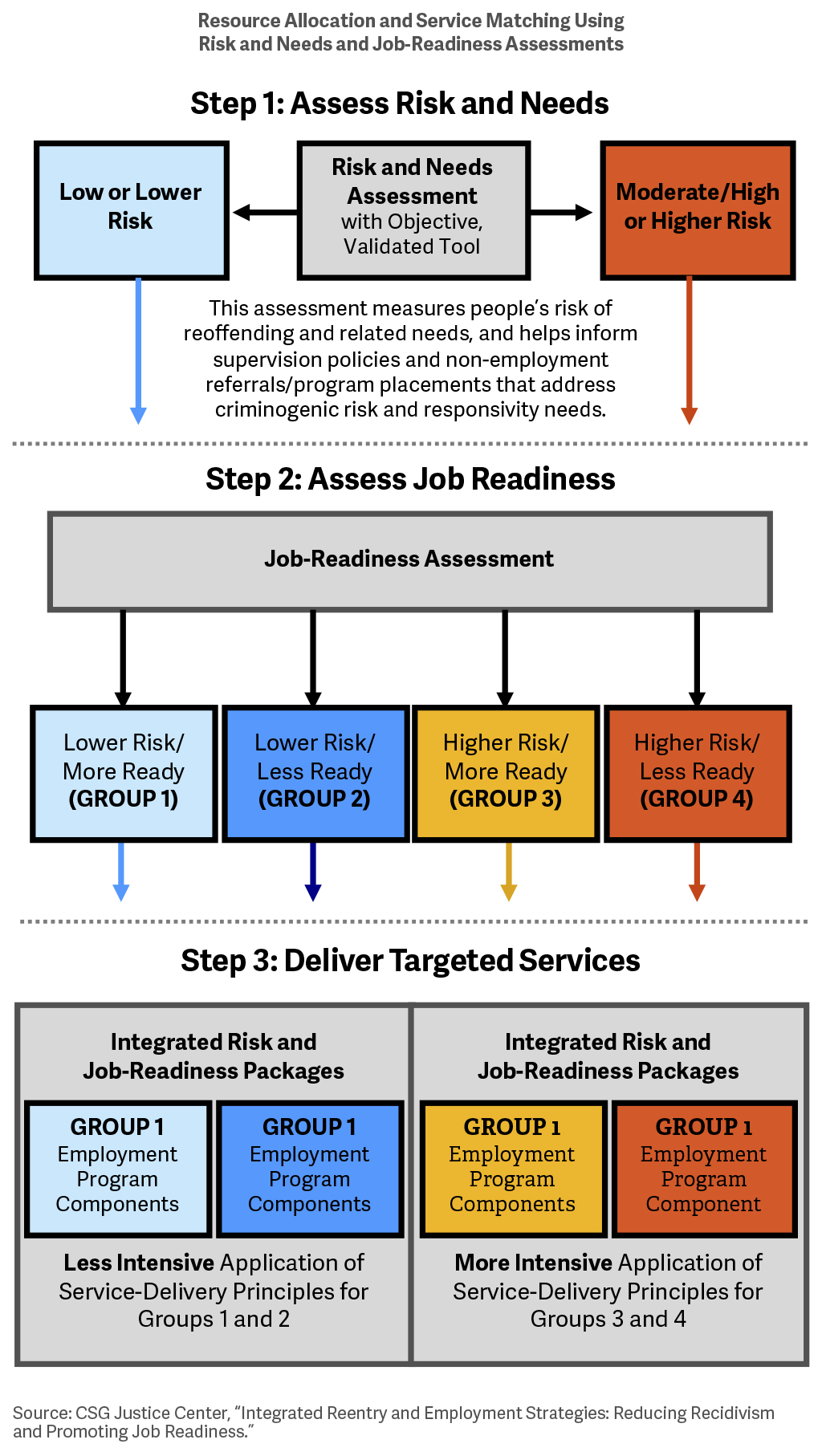

In addition to reducing barriers to employment, employment strategies need to be integrated into reentry strategies and focus on connecting people to appropriate forms of assistance and support tailored to their job readiness and risk and needs. Not everyone has the same likelihood of recidivating, and people at a higher risk of reoffending require more intensive interventions to address underlying criminogenic needs than lower-risk people. Similarly, people who are less job ready need different services than those who are more job ready. Depending on their needs and experiences, people leaving prison or jail may require job search services, employment training (hard and soft skills), or more intensive programs, such as supportive employment, that help people obtain and maintain employment. Integrated reentry and employment services need to reserve the most intensive supervision and services for people who have the highest risk of reoffending and lowest job readiness.[48] States can use federal workforce development funds to support training and education programs to ensure that people reentering the community have the necessary skills to meet employers’ needs.

What it looks like

- Actively engage local business leaders, chambers of commerce, and industry associations to talk about the benefits and challenges of hiring a person with a criminal record and understand hiring needs within specific industries.

- Reduce barriers to employment by adopting fair-hiring policies and expanding record clearance policies.

- Lift unnecessary occupational licensing restrictions.

- Leverage workforce development funds to support correctional and reentry programs.

- See Case Study: States adopt practices to increase coordination between correctional, labor, and employment agencies

- See Case Study: Employment program provides jobs and services

- Ensure that people have immediate access to state identification after incarceration.

- See Case Study: California provides state identification to people leaving prison

- Tailor employment services for people leaving prison and jail to address their criminogenic needs and job readiness.

- See Case Study: Wisconsin’s Integrated Reentry and Employment pilot site improves efforts to prepare people for the workforce and reduce recidivism

- See Case Study: Florida pilots Integrated Reentry and Employment Strategies to reduce recidivism and improve job readiness

Key questions to guide action

- Do people who lack state identification automatically receive it upon release from prison or jail?

- Are people in the criminal justice system prioritized for employment services based on their risk of reoffending?

- How can your state engage the business community in reducing barriers to employment?

- What steps might your state take to reduce the impact a criminal record has on a person’s ability to find employment, when appropriate?

- How can your state support local initiatives to reduce barriers to employment?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

Additional Resources

Integrated Reentry and Employment Strategies

Job attainment alone is unlikely to reduce recidivism or result in long-term job retention. Further, people have varying levels of job readiness and risk of reoffending, which require programming and employment support tailored to their needs. Corrections, reentry, and workforce agencies need to work together to design employment programs that address criminogenic needs and job readiness.

To ensure the greatest return on investment, policymakers, administrators, and practitioners should collaboratively determine if the right employment resources are focused on the right people at the right time. To learn more, see the Integrated Reentry and Employment Strategies white paper.

When assessing a community’s ability to integrate the efforts of criminal justice and workforce development systems, state and local policymakers and practitioners need to identify the unique challenges and opportunities in their communities. There are key questions that can help guide communities toward establishing policy and programmatic frameworks that ensure existing resources for reentry and employment services are leveraged in the most impactful way. To learn more, see Four Questions Communities Should Consider When Implementing a Collaborative Approach.

Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act

The federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which was signed into law in 2014 and implemented by states in July 2016, is the nation’s primary source of federal funding for workforce development. Its main goal is to provide job seekers with the assistance needed to obtain employment and to meet employers’ needs for qualified workers. WIOA prioritizes employment services for veterans; recipients of public assistance; economically disadvantaged youth and adults, including people who are homeless; people with criminal records; and people who have limited basic skills and work experience, in addition to funding services for other populations. The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) requires states to report on the number of people receiving WIOA-funded services according to the barriers to employment they face, such as homelessness or a criminal record. For additional information, see The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act: What Corrections and Reentry Agencies Need to Know.

State-issued identification

State-issued identification is frequently required to access social services, secure housing, and apply for employment—all of which can play a crucial role in a person’s successful reintegration into the community after incarceration. To ensure that people are able to obtain state-issued identification after incarceration, states can employ a variety of strategies, such as mandating that a state’s department of corrections (DOC) collaborate with the state’s department of motor vehicles (DMV) to ensure that people have state identification upon release, or authorizing a state’s DMV to accept DOC identification or prison release papers as a form of identification. To learn more, see State Identification: Reentry Strategies for State and Local Leaders.

Collaboration between employers and policymakers

In many parts of the country, there are more job openings than there are people to fill them. As a result, a growing number of businesses—both large and small—are identifying people who have criminal records as an untapped part of the labor market. To understand and address challenges associated with hiring people who have criminal records, a two-way dialogue between business leaders and policymakers is required. To assist corrections, workforce, and reentry administrators and practitioners in engaging employers on the benefits of hiring people with criminal records, see Effective Strategies for Engaging Employers.

Collateral consequences

Across the country, there are approximately 40,000 legal and regulatory sanctions and restrictions beyond a court sentence—commonly known as collateral consequences—that can affect people’s ability to gain housing, employment, education, and civic participation after leaving the criminal justice system. State leaders can assess the extent of these barriers to reentry in their state by using the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, a searchable database of collateral consequences in all U.S. jurisdictions.

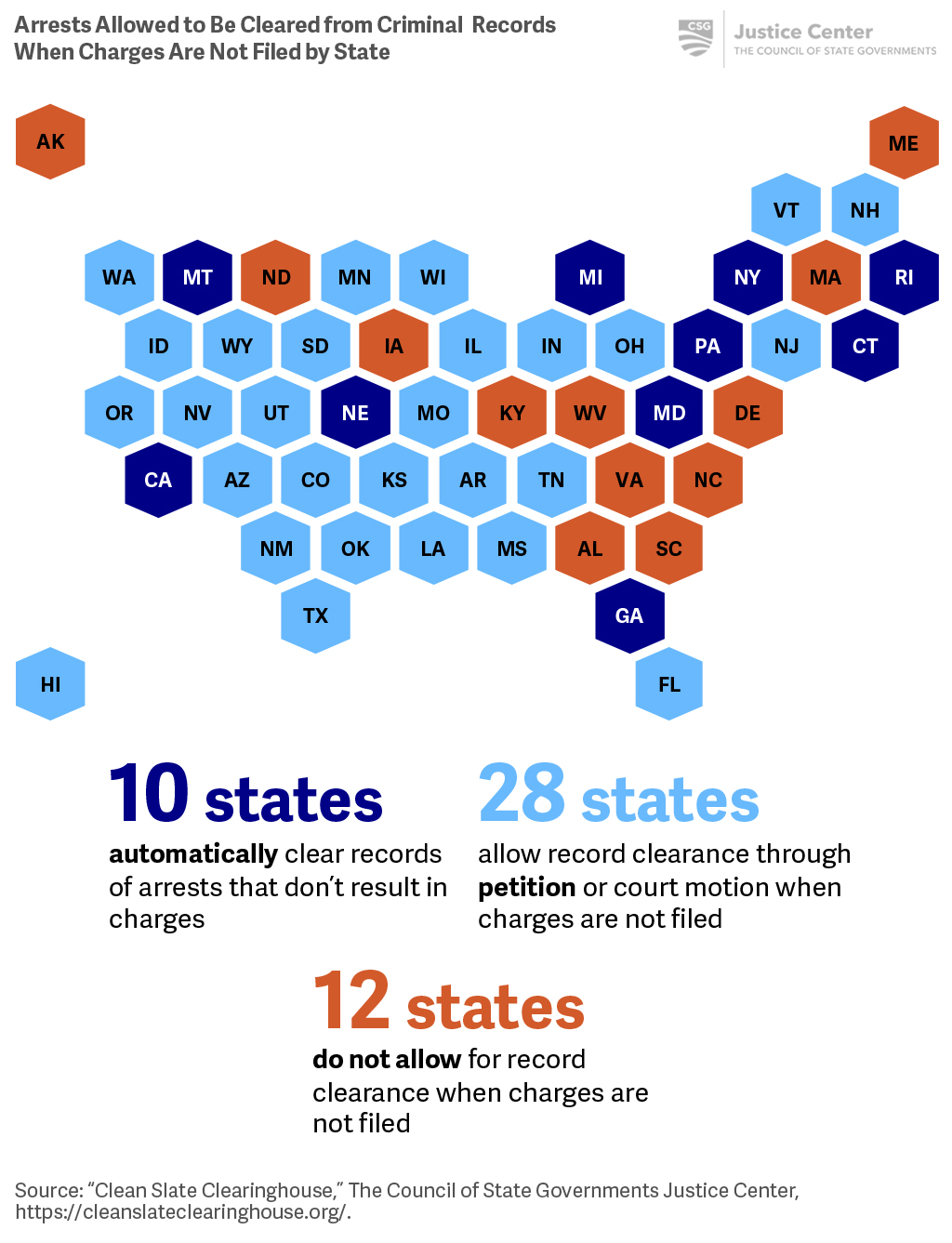

Clean Slate Clearinghouse

Record clearance—removing criminal history information from easy public access—may help provide people with an opportunity to put their pasts behind them. The Clean Slate Clearinghouse provides people with criminal records, legal service providers, and state policymakers with information on juvenile and adult criminal record clearance policies in all U.S. states and territories. To understand your state’s criminal record clearance policies, see the Clean Slate Clearinghouse.

Employment services need to be tailored to people’s job readiness and criminogenic risk and needs.

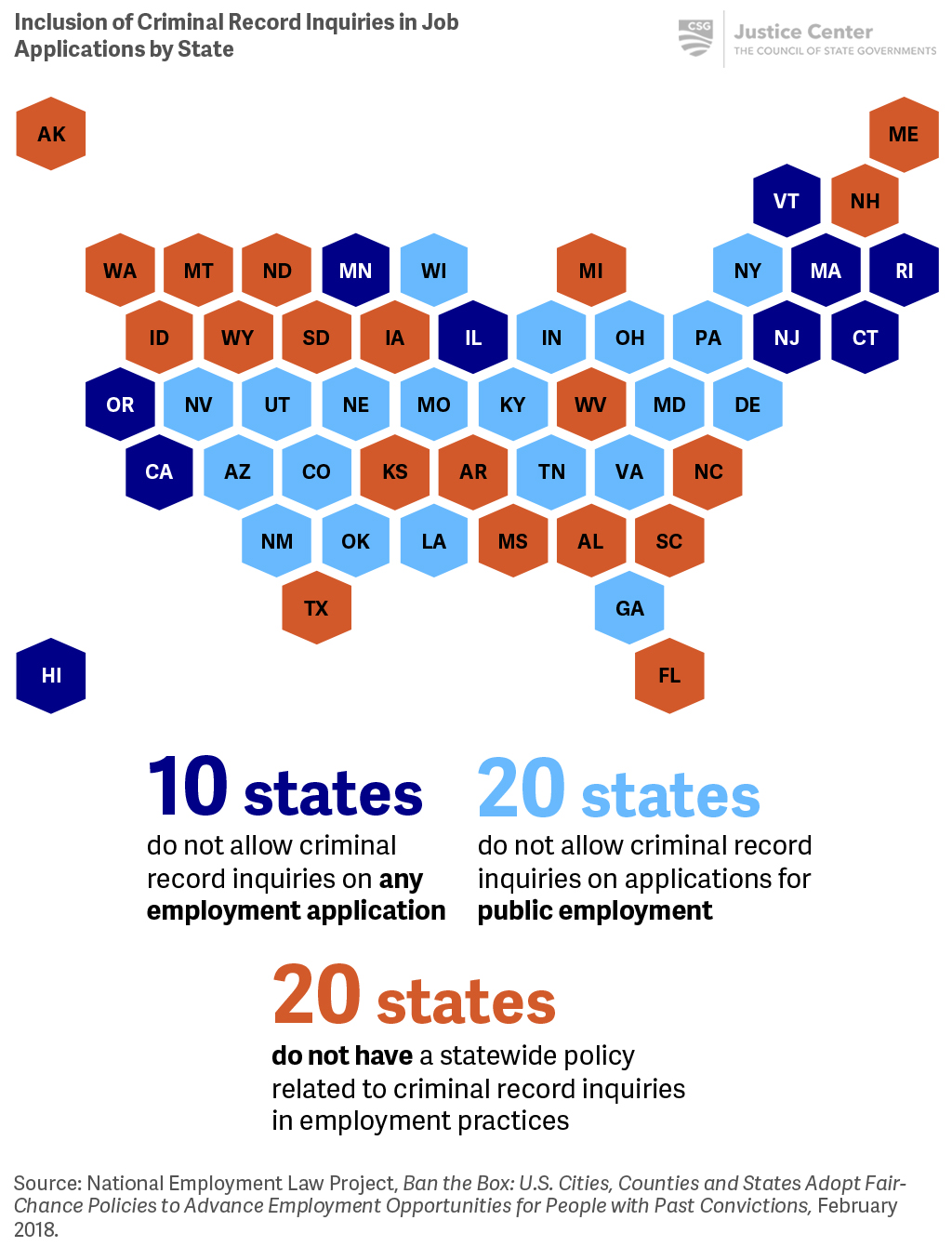

More than half of states have statewide laws or policies related to the consideration of criminal records in hiring decisions.

“National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction,” https://niccc.csgjusticecenter.org/map/.

Devah Pager, “The Mark of a Criminal Record,” American Journal of Sociology 108, no. 5 (2003): 937–75.

Ibid.

Cherrie Bucknor and Alan Barber, The Price We Pay: Economic Costs of Barriers to Employment for Former Prisoners and People Convicted of Felonies, (Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2016).

Megan C. Kurlychek, Robert Brame, and Shawn D. Bushway, “Enduring Risk? Old Criminal Records and Predictors of Future Criminal Involvement,” Crime & Delinquency 53, no. 1 (2007): 64–83.

CSG Justice Center, Integrated Reentry and Employment White Paper (New York, NY: CSG Justice Center, 2013).

Supportive employment programs can help certain people, including those who have behavioral health needs, intellectual disabilities, and/or who are in the criminal justice system, find jobs and provide ongoing support and services to maintain employment.

Case Study

States adopt practices to increase coordination between correctional, labor, and employment agencies

Several states, including New Jersey, use federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) funds to hire reentry specialists who are trained to address the employment needs of people returning to the community after incarceration. The reentry specialists work out of one-stop career centers and, in addition to serving other types of clients, are points of contact for people who are referred to the one-stop center by corrections and reentry staff, as well as for job seekers who have criminal records who visit the center without referral.[49]

Washington State’s correctional facilities use a team-teaching approach in which students learn from two teachers: one who provides job training on automotive technology, carpentry, and other vocational skills, and one who teaches basic math, reading, and English. This model allows students to learn essential skills while also receiving vocational training in the area of their choice.[50]

Further, the state offers pre-apprenticeship programs to prepare incarcerated men and women for entry into construction trades after release. The Trades Related Apprenticeship and Coaching (TRAC) program is a registered pre-apprenticeship program offered at the women’s prison and provides participants with a more streamlined entry into apprenticeships upon release. In addition, TRAC partners with an organization to provide wrap-around services to women after they are released and enter the apprenticeship. The men’s prisons offer 10 construction-trades related training programs through the local community colleges. The state is working with construction trades unions to recognize the hours that incarcerated workers have accumulated while working in prison that can count toward the apprenticeship. In 2016, Washington’s governor issued an executive order directing pathways to be developed to post-secondary education and apprenticeships for people who are incarcerated.

[49] The Council of State Governments Justice Center, “The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act: What Corrections and Reentry Agencies Need to Know,” (New York, NY: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, May 2017).

[50] Ibid.

Case Study

Employment program provides jobs and services

The New York City-based Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO) is one of the nation’s largest jobs programs for people who were formerly incarcerated. The program offers participants temporary, paid jobs that provide structure, exposure to a work environment, and income. In addition, CEO provides participants with job readiness classes, job coaching, and other services, all aimed at making people more employable and preventing their return to prison. CEO prioritizes interventions for people who are at a high risk of reoffending. When participants are deemed “job ready,” they begin working with a job developer to find full-time, unsubsidized employment. CEO then provides one year of financial incentives and job-retention services.

For additional information, see What Works in Reentry Clearinghouse: Center for Employment Opportunities.

Case Study

California provides state identification to people leaving prison

California requires the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and the California Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) to ensure that all eligible people have valid identification cards when they are released from state prison. At the local level, Los Angeles County and San Diego County have created programs in coordination with the DMV that provide state identification three to four months prior to a person’s release from jail.[51]

[51] The Council of State Governments Justice Center, “State Identification: Reentry Strategies for State and Local Leaders” (New York, NY: CSG Justice Center, 2016).

Case Study

Wisconsin’s Integrated Reentry and Employment pilot site improves efforts to prepare people for the workforce and reduce recidivism

In 2015, The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance selected Milwaukee County, Wisconsin as one of only two sites in the country to pilot an innovative approach to reduce recidivism and increase the employability of people returning to the community from prison. The Milwaukee County Integrated Reentry and Employment Strategies (IRES) Pilot Project focuses on operationalizing a level of cross-systems coordination among corrections and workforce agencies, including community-based ones. The project is guided by a steering committee that includes stakeholders from both the corrections/reentry and workforce development fields and is led by an executive committee of state leaders.

The first year of the project focused on analyzing the risk and job-readiness profiles of people returning to Milwaukee County from WI DOC facilities, understanding the landscape of workforce service providers in the county, and identifying WI DOC processes for assessing both the criminogenic risk and job readiness of those people at admission to prison and upon release and mechanisms for connecting them to appropriate workforce services upon release. The CSG Justice Center found that WI DOC staff administer risk assessments and make referrals to evidence-based cognitive programming, based on assessment results, but workforce programming is not targeted to individuals’ assessed levels of job readiness. Supervision officers often make referrals to community-based workforce agencies upon release, but referrals are not driven by risk or job-readiness assessment information. Milwaukee County is resource rich regarding workforce services for adults returning from incarceration; however, many workforce agencies do not deliver services in accordance with evidence-based approaches or target criminogenic needs when appropriate.

Based on the results of this analysis, the steering committee is working to implement the following recommendations with assistance from the CSG Justice Center:

- Determine each WI DOC facility’s capacity to provide evidence-based cognitive programming to all people assessed as moderate to high risk of reoffending and increase capacity through trainings in evidence-based interventions, if needed.

- Assess the job readiness of everyone upon admission to WI DOC facilities.

- Formalize and develop appropriate institution-based programming for people with different risk and job-readiness levels.

- Contract with a centralized agency to complete job-readiness assessments and coordinate referrals to appropriate workforce service providers.

- Ensure that people are referred to the most appropriate workforce agency based on their individual risk and job readiness levels.

- Assess service gaps and, where appropriate, provide trainings for workforce agencies on evidence-based practices that help reduce recidivism. Redesign contracts to encourage integration of recidivism-reduction interventions into workforce programs as well as to promote specialization among workforce providers or the development of service tracks for people with different risk and job-readiness groupings.

Leaders in Milwaukee County and across Wisconsin are also working with the CSG Justice Center to review state legislation and engage business leaders in an effort to minimize barriers to employment for people with criminal records.

For additional information, see Increasing Job Readiness and Reducing Recidivism Among People Returning to Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, from Prison.

Case Study

Florida pilots Integrated Reentry and Employment Strategies to reduce recidivism and improve job readiness

In early 2015, Palm Beach County, Florida, was selected by The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance as one of only two sites in the country to pilot an innovative approach to reducing recidivism and increasing the employability of people returning to the community from prison and jail. The Palm Beach County Integrated Reentry and Employment Strategies (IRES) pilot project focuses on operationalizing a level of cross-systems coordination among corrections and workforce agencies. The project is guided by a steering committee that includes stakeholders from both the corrections/reentry and workforce development fields.

The first year of the project involved analyzing risk and job-readiness profiles of people returning to Palm Beach County from Florida Department of Corrections (FL DOC) facilities and county jails, understanding the employment programming available through the three contracted community-based reentry service providers and the workforce development board, and identifying FL DOC and Palm Beach County Criminal Justice Commission (CJC) processes for assessing both the criminogenic risk and job readiness of people and mechanisms for connecting them to appropriate employment services upon release. The CSG Justice Center found that:

- CJC facilitates a high level of coordination among community-based reentry service providers who administer risk and needs assessments before or after release for people returning to Palm Beach County. While program enrollment is prioritized for people at a high risk of reoffending, not all providers are currently able to deliver services in a way that targets criminogenic risk and need factors.

- Workforce programming is not consistently targeted to people’s assessed level of job readiness.

- Enrollment rates are highest for people returning from Sago Palm Reentry Center, where community-based reentry service providers begin programming before release.

- Risk and needs assessment information is collected in a central database maintained by the CJC that is accessible to community-based reentry service providers, but the data collected makes program impact evaluations difficult.

Based on these findings, the steering committee is working to implement a range of recommendations with assistance from the CSG Justice Center, including:

- Assess the capacity of contracted providers to serve higher-risk people and fund training in recidivism-reduction interventions, when needed. Ensure that contracts through the CJC promote evidence-based service-delivery principles.

- Refer people to reentry service providers best equipped to meet their criminogenic risk and needs based on assessment results.

- In partnership with the business community, develop a standard definition of job readiness. Adopt a single job-readiness assessment tool to be used by community-based reentry service providers upon intake, and assign people to appropriate programming based on the results.

- Develop more programming tracks targeted to people with differing risk levels and needs, particularly for people who are less job ready.

- Ensure consistent use of the central database maintained by CJC among service providers for tracking referrals, assessments, progress, and service delivery.

Leaders in Palm Beach are also working with the CSG Justice Center to engage business leaders in an effort to minimize barriers to employment for people with criminal records. For additional information, see Increasing Job Readiness and Reducing Recidivism among People Returning to Palm Beach, FL, from Prison and Jail.