Part 3, Strategy 2

Action Item 3: Improve the efficiency and consistency of the parole decision-making process and preparation for release.

Why it matters

At least 95 percent of people in state prisons will eventually be released.[39] Exactly when they are released often depends upon release decisions made—at least in part—by a state’s parole board.[40] Decisions by parole boards to increase or decrease the number of people released from prison can have a significant impact on the size of a state’s prison population. Far too often, corrections agencies and parole boards grapple with three common challenges that result in high costs due to increased lengths of stay and increase the chance of releasing people from prison without supervision:

- Coordination: Lack of coordination between parole boards and corrections agencies about which programs people need for release, resulting in people not receiving the programming they need to be eligible for release prior to their initial parole hearing.

- In-prison programming: Limited capacity of in-prison programming limits the ability of people, particularly those with short sentences, to receive programming they need to complete in order to be eligible for parole prior to their initial parole hearing.

- Community-based services: Limited availability of appropriate housing options and community-based treatment and programming to connect people to upon release that slows the parole release process.

Inefficiencies that slow parole processing and delay the release of eligible candidates to parole supervision increase the likelihood of people serving their entire sentence in prison and, as a result, returning to their communities without supervision or support. The likelihood of recidivism is highest within the first year of release and decreases in each subsequent year, which is why supervising people in the months after release is an important tool to increase public safety, but supervision terms beyond three to five years yield limited results.[41]

To ensure that people are ready for parole at their initial parole hearing, corrections departments must assess people for risk of recidivism and criminogenic needs and prioritize risk-reduction programming and treatment for those who are at a high risk of reoffending and have the greatest needs. Further, corrections departments need to ensure availability of programs and timely placement of people into these programs. This allows people to complete programming milestones by their initial parole hearing and continue programming in the community as needed. Clear guidelines can also help corrections agencies coordinate with parole boards on case planning to prepare people for release. Corrections agencies and parole boards need to collaborate to identify risk-reduction requirements for parole and develop reentry plans that support timely release.

To increase transparency and consistency in release decision making, many parole boards are also adopting guidelines that account for factors that demonstrate a person’s readiness for release, including risk of reoffending and criminogenic needs, offense severity, program completion, and institutional behavior.

States have taken many other steps to reduce delays in release decision making. Some have established goals to release a certain percentage of people by risk level each year, releasing more people who are at a low risk of reoffending than those who are at a high risk. Other states require people to be released within a specified period after their initial parole date absent compelling circumstances to detain them further. Some states are actively supporting reentry efforts that connect people to supports such as housing, treatment, and employment upon release, without which, a person’s release into the community may be delayed.

What it looks like

- Prioritize finite prison space for people convicted of the most serious offenses, and prepare other people for release at their minimum parole eligibility, absent compelling circumstances to hold them beyond this time.

- See Case Study: Idaho requires people convicted of property and drug offenses to be released near initial parole release date

- Use criminogenic risk and needs assessments to determine a person’s programming needs in prison and to prioritize programs for people who have the highest risk of reoffending and greatest needs.

- Require paroling authorities to collaborate with institutional corrections agencies to agree on the risk-reduction requirements for parole and to develop reentry plans that support timely release.

- Require parole boards to use parole guidelines that account for factors that demonstrate a person’s readiness for parole, including risk and needs assessment results, to inform release decision making.

- See Case Study: Alabama develops structured approach to parole release decisions

- Reduce barriers to reentry through supporting a range of housing, treatment, and programming options for people upon release from prison.

- See Case Study: Texas invests resources to reduce parole delays

Key questions to guide action

- What percentage of people are released from prison in your state within three months of reaching their minimum sentence? What percentage of people who left prison in your state last year were released without supervision?

- What are the most commonly documented reasons for denials of parole release at an initial hearing?

- How does the paroling authority in your state currently decide who to release to parole supervision?

- How do your state’s corrections agency and the parole board collaborate to reduce release delays?

- How does your state prepare people for reentry into the community and what improvements are necessary?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

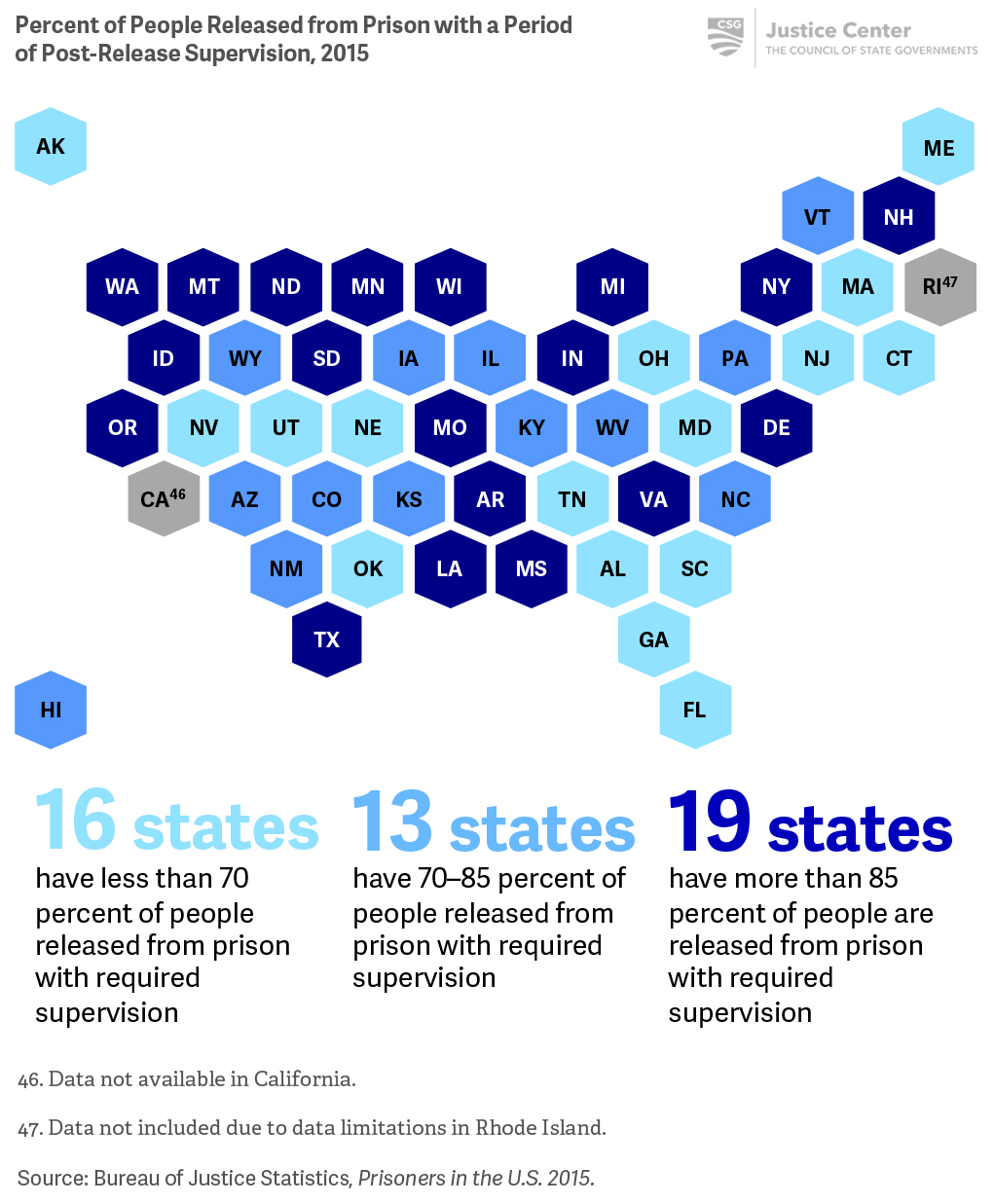

The majority of states require a period of post-release supervision for people leaving prison.

Timothy Hughes and Doris James Wilson, Reentry Trends in the United States (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2002).

State legislatures establish sentencing terms in statute and judges typically prescribe a person’s sentence length. The majority of states have parole boards determining release decisions for most people leaving prison; Ebony Ruhland et al., The Continuing Leverage of Releasing Authorities: Findings from a National Authority (Minneapolis, MN: Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice, 2016).

Matthew Durose, Alexia Cooper, and Howard Snyder, Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 30 States in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2014); The Pew Charitable Trusts, Max Out: The Rise in Prison Inmates Released Without Supervision (Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2014).

Case Study

Idaho requires people convicted of property and drug offenses to be released near initial parole release date

In 2014, Idaho enacted Justice Reinvestment legislation requiring the Commission of Pardons and Parole (Commission) to establish clear guidelines and procedures that aimed to reduce the amount of time that people convicted of property or drug offenses spent in prison beyond their minimum sentence, while ensuring that the Commission retains discretion in individual cases. The legislation requires the Idaho Department of Correction and the Commission to submit annual reports to the legislature and governor that document the percentage of people sentenced to prison for property and drug offenses who are released prior to serving 150 percent of their minimum sentence. In 2017, approximately 87 percent of people convicted of property and drug offenses were released prior to serving 150 percent of their minimum sentence, compared to 75 percent in 2014.[42]

[42] Idaho Department of Corrections, Justice Reinvestment in Idaho: Impact on the State (Boise, ID: Idaho Department of Corrections, 2018).

Case Study

Alabama develops structured approach to parole release decisions

In 2015, Alabama enacted Justice Reinvestment legislation requiring its parole board to follow structured parole guidelines that take into account risk of reoffending and criminogenic needs, institutional conduct, and prison programming, when making release decisions. This structured decision-making process helps the board make more consistent, transparent, and efficient parole decisions. Further, parole guidelines can help the board track releases by risk level to understand who is being released close to their minimum parole eligibility date and who is not.

In the first six months of implementing these guidelines, the parole grant rate steadily increased, and the majority of people being released were assessed as being at a low or moderate risk of reoffending.[43]

[43] CSG Justice Center analysis of Alabama Board of Pardons and Parole data.

Case Study

Texas invests resources to reduce parole delays

Between 1985 and 2005, the Texas prison population grew 300 percent, and by 2007, the prison population was projected to grow by an estimated additional 17,000 beds by 2012, at a cost of $2 billion. Increased probation revocations, reduced treatment capacity, and reduced parole approvals contributed to the state’s prison population growth. Parole grant rates were much lower than the parole board’s own guidelines recommended and many people’s release to parole was delayed due to a lack of in-prison and community-based treatment programs.

To address the drivers of prison growth, Texas reinvested $241 million in the 2008–2009 biennium to increase options for responding to probation and parole violations and increase substance addiction and mental health treatment capacity. These investments allowed the state to reduce release delays for people at a low risk of reoffending and increase the percentage of people approved for release to parole. Since 2007, Texas has averted more than $3 billion in corrections costs, and the prison population fell from 152,671 people in 2007 to 145,409 in 2017, allowing the state to close 8 prisons.[44] The reduced prison population did not result in more crime; in fact, crime rates fell 31 percent between 2007 and 2016.[45]

[44] CSG Justice Center Lessons from the States: Reducing Recidivism and Curbing Corrections Costs Through Justice Reinvestment (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2013); Texas Legislative Budget Board, “Adult and Juvenile Correctional Populations: Monthly Report,” (Austin, TX: Texas Legislative Budget Board, 2007–2017).

[45] U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Crime in the United States, 2007 and 2016.”