Part 2, Strategy 3

Action Item 3: Provide supervision officers with tools to respond swiftly and appropriately to the behavior of people on supervision.

Why it matters

Historically, supervision officers have focused on monitoring compliance and reacting to supervision violations, which leads officers to miss opportunities to reinforce positive behavior and facilitate change. Adopting a more balanced and proactive approach to probation and parole supervision instead can hold people accountable for their inappropriate behavior and reduce their likelihood of reoffending. Supervision officers can support people’s rehabilitation by helping them build skills to succeed in the community and proactively engaging them in treatment and services before they violate any of their supervision conditions.

Research shows that applying four positive reinforcements for every sanction is optimal for behavior change to occur.[31] To that end, supervision officers need authority to respond to violations and positive behavior with a range of responses. Incentives can range from verbal praise to reduced reporting conditions or early discharge from supervision. Sanctions vary depending on the severity of the violation and can range from a verbal reprimand to increased reporting requirements or short periods in jail. Research shows that jail sanctions are not more effective than community-based sanctions, so jurisdictions should consider using jail time sparingly.[32] Best practices call for sanctions and incentives that are swift, certain, and proportionate to supervision behavior so that people on supervision see the response as a direct consequence of their behavior.[33] For additional information, see Part 3, Strategy 2.

Some supervision agencies develop specialized caseloads to focus on people with particular needs, such as mental illnesses, or who have committed certain offenses, such as domestic violence. In addition to being trained on RNR principles and effective supervision strategies, officers supervising people on these specialized caseloads often receive training targeted at addressing the specific needs of those people. For example, officers with a specialized caseload for people who have mental illnesses may receive training not only on common mental health diagnoses and behaviors, effective supervision and intervention strategies for people who have mental illnesses, and de-escalation techniques, but also on how the state’s behavioral health system works and how to connect people to necessary resources. Specialized caseloads may be smaller than a general caseload to allow officers to spend more time on case management to promote each person’s success on supervision.

Further, investing in technology to support effective supervision can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of supervision agencies. Many agencies are transitioning from using a paper-based system to supplying officers with laptops and smartphones to ensure that officers have access to the latest information when they’re away from their desks, such as when they conduct home and collateral visits with treatment providers, employers, and the supervisee’s family members. Agencies are also updating data systems to automate and streamline data entry to facilitate sharing data across criminal justice agencies and reduce time spent on administrative tasks so that supervision officers can spend more of their time supervising people on their caseloads.

To ensure that supervision agencies are reducing recidivism and helping people succeed in the community, they need to measure performance and track recidivism outcomes for people on supervision as described in Part 2, Strategy 1 of this report. States have tackled performance measurement in a variety of ways, from hiring research staff and requiring annual reports to the governor and legislature, to updating IT systems and creating interactive web-based data systems to track the latest performance metrics. (For additional information on performance measurement, see Part 3, Strategy 4.)

What it looks like

- Require supervision officers to use a range of incentives for good behavior on supervision.

- Promote using a greater proportion of incentives than sanctions to encourage behavior change on supervision.

- Permit the use of a range of sanctions, including short jail stays, when appropriate, to respond to supervision violations.

- See Case Study: States use incentives and sanctions to respond to behavior on supervision

- Establish specialized caseloads, where appropriate.

- See Case Study: Connecticut provides enhanced supervision for specialized probation caseloads

- Provide supervision officers with necessary technology.

- See Case Study: States update technology used by supervision agencies

- Track performance measures and recidivism outcomes.

Key questions to guide action

- Do supervision officers in your state use a range of incentives to respond to violations? How frequently are they used compared to sanctions?

- Do supervision officers have authority to use short jail stays when appropriate?

- How can your state ensure that supervision agencies have the technology they need to support effective supervision practices and measure outcomes?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

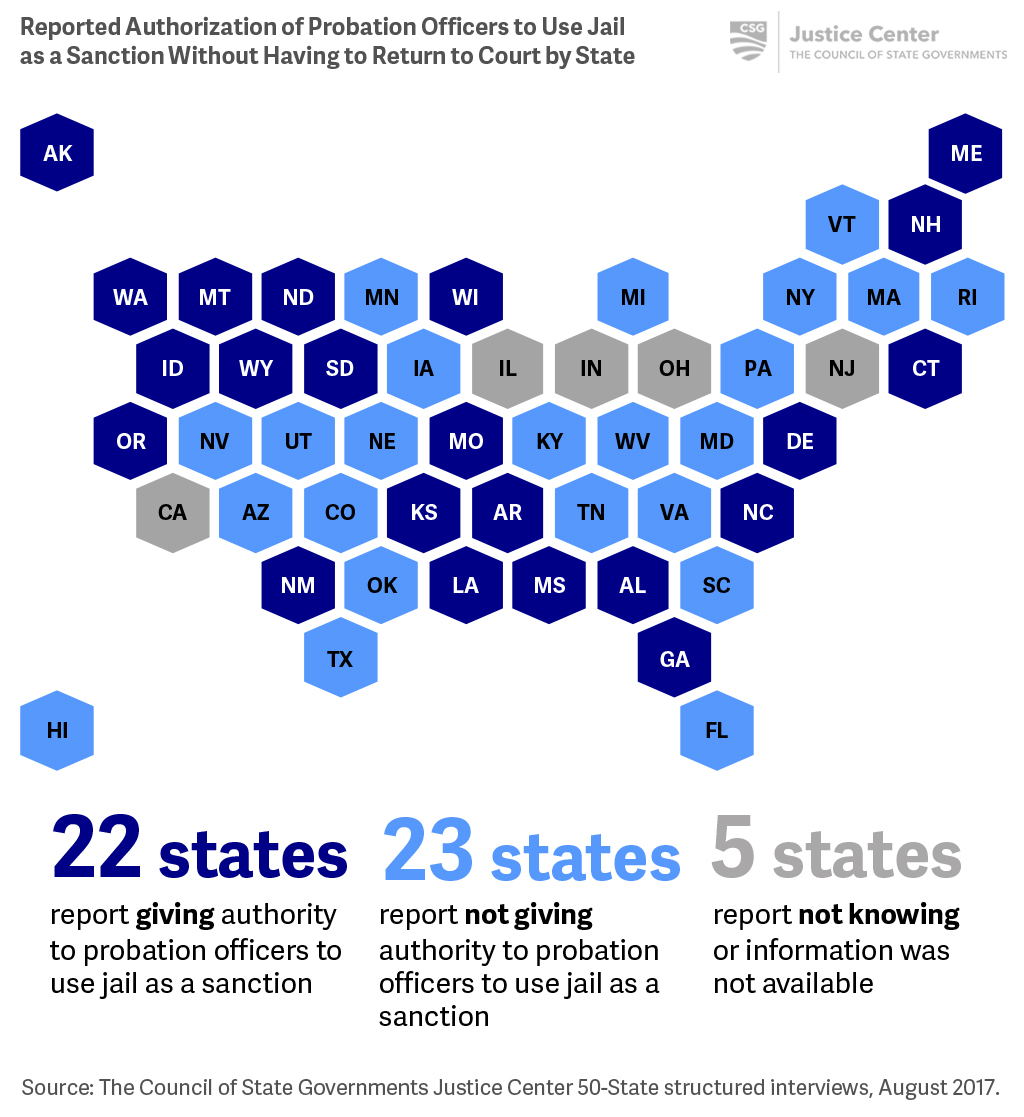

23 states do not allow probation officers to use short jail stays as a sanction without returning to court.

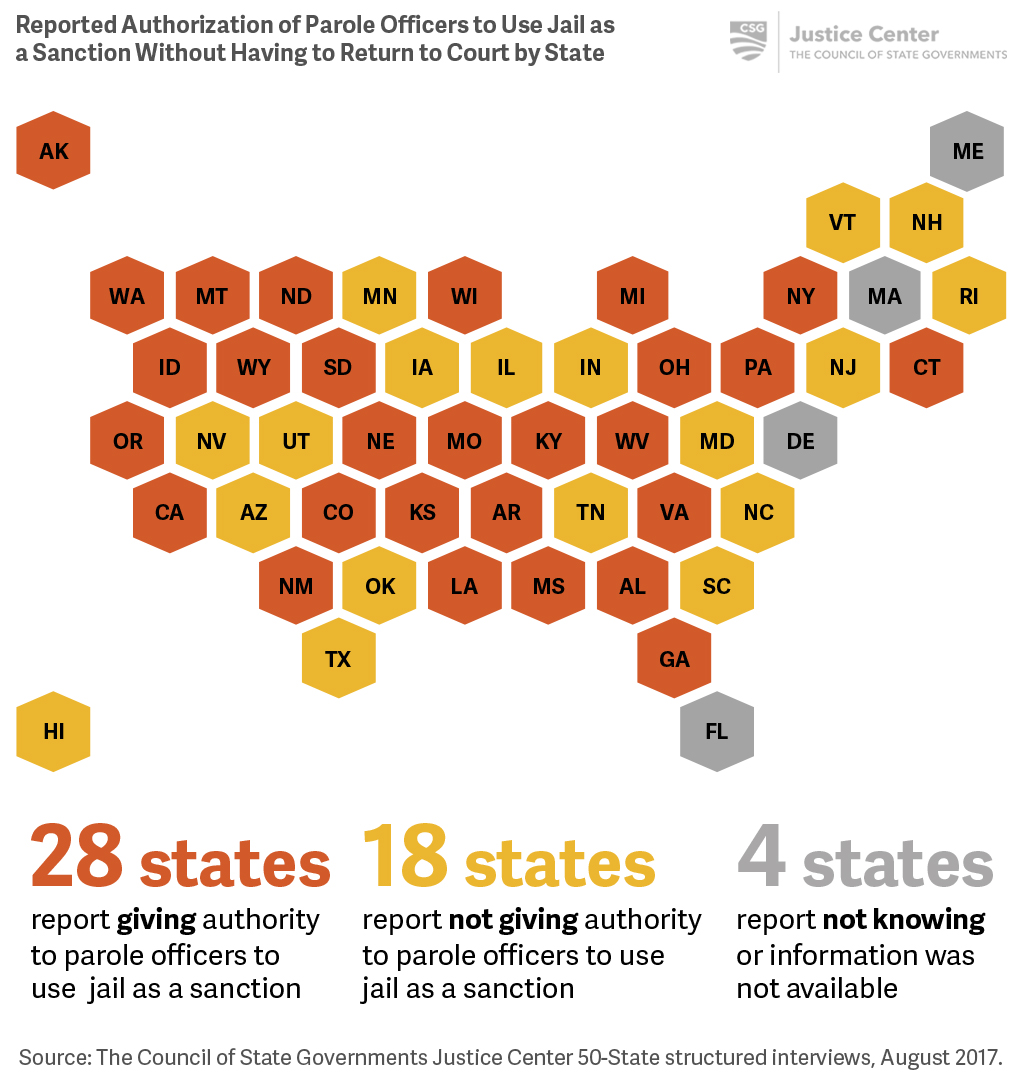

18 states do not allow parole officers to use short jail stays as a sanction without returning to court.

Additional Resources

Innovations in Supervision

The U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) administers the Innovations in Supervision program, which provides funding for states, local governments, and federally recognized tribal governments to develop and test innovative strategies and implement evidence-based probation and parole approaches that effectively address people’s criminogenic risk and needs and reduce recidivism. The program is part of BJA’s Innovations Suite of programs, which invest in the development of practitioner-researcher partnerships that use data, evidence, and innovation to assess problems and create strategies and interventions that are both effective and economical. For additional information, see Second Chance Act Innovations in Supervision.

Paul Gendreau, and Claire Goggin, “Correctional treatment: Accomplishments and realities,” in Correctional Counseling and Rehabilitation, ed. Patricia Van Voorhis, Michael Braswell, and David Lester (Cincinnati, OH: Anderson, 1997); Eric J. Wodahl et al., “Utilizing Behavioral Interventions to Improve Supervision Outcomes in Community-Based Corrections,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 38, no. 4 (2011): 386-405.

Eric J. Wodahl, John H. Boman IV, and Brett E. Garland, “Responding to Probation and Parole Violations: Are Jail Sanctions More Effective Than Community-Based Graduated Sanctions?” Journal of Criminal Justice 43, no. 3 (2015): 242-250.15): 242-250.

Daniel S. Nagin, Francis T. Cullen, and Cheryl Lero Johnson, “Imprisonment and Reoffending,” Crime and Justice 38, no 1 (2009): 115-200.

Case Study

States use incentives and sanctions to respond to behavior on supervision

Supervision agencies across the country are beginning to incorporate systematic use of incentives in addition to sanctions. To achieve behavior change, supervision agencies must incorporate both sanctions to respond to negative behavior and incentives to recognize and reward prosocial behavior. These responses are applied shortly after a person demonstrates positive or negative behavior in order for people on supervision to see the sanction or reward as a direct consequence of their behavior.

To guide these responses to behavior on supervision, states such as Alaska, Nebraska, and Utah established supervision response matrices, which include a range of incentives to encourage positive behavior and sanctions to respond to noncompliance. Kansas and North Carolina both delegate authority to supervision officers to impose two- to three-day jail sanctions for probation violations without requiring the officers to petition the court, and Alabama permits a similar response for probation and parole violations.

Case Study

Connecticut provides enhanced supervision for specialized probation caseloads

In Connecticut, there are a range of specialized caseloads to help people on probation who have specific needs. When people on probation are at imminent risk of violating the conditions of probation, but not committing a new crime, they may be supervised by a specially-trained officer in the probation agency’s technical violations unit (TVU). TVU officers have fewer people on their caseloads than regular officers, and people on their caseloads are prioritized for community-based services and treatment, which allows TVU officers to spend more time helping people on their caseloads address their criminogenic needs.

Connecticut has other specialized units, including a probation transition program, which provides services to people who are transitioning back to the community from incarceration, and a women’s case management model, which provides gender-responsive services to females on probation. For more information, see Connecticut’s specialized probation caseloads.

Case Study

States update technology used by supervision agencies

States are identifying opportunities to update the technology that supervision agencies use to automate and streamline data entry, develop systems for people on limited supervision to check in with their probation officer remotely, and share risk and needs assessment and restitution information across agencies.

Georgia is updating its IT system to automatically flag people who are eligible for early discharge from supervision and autopopulate most of the information necessary for court review.

Nebraska purchased electronic tablets to allow parole officers to access real-time information in the field. Nebraska’s Division of Parole Supervision also uses behavior management software that incorporates the most recent research on effective community supervision practices into a structured electronic tool that helps parole officers choose appropriate responses to prosocial and noncompliant behavior on supervision. The software also allows for measuring performance, including the ratio of behaviors to responses and the time between behavior and responses. Such measures help managers analyze how well parole officers are following evidence-based practices and department policies.

North Carolina’s Department of Public Safety developed a smartphone app to help officers manage their caseloads in the field and perform their duties more effectively and efficiently while increasing their own safety. All officers now have a smartphone with an app that

- Allows them to search their caseloads, schedule visits, and access contact information and driving directions;

- Check someone’s criminal history, identify any upcoming court appearances, and learn whether there are any known safety issues, such as gang affiliation or history of domestic violence, before meeting with the person;

- Record their findings at the time of their visit cutting down on time-consuming paperwork and improving real-time data collection; and

- Take photos of the people on their caseload, as well as any relevant evidence or associates, which can then be included in the person’s database file.