Part 2, Strategy 1

Action Item 2: Expand recidivism tracking to include the probation population.

Why it matters

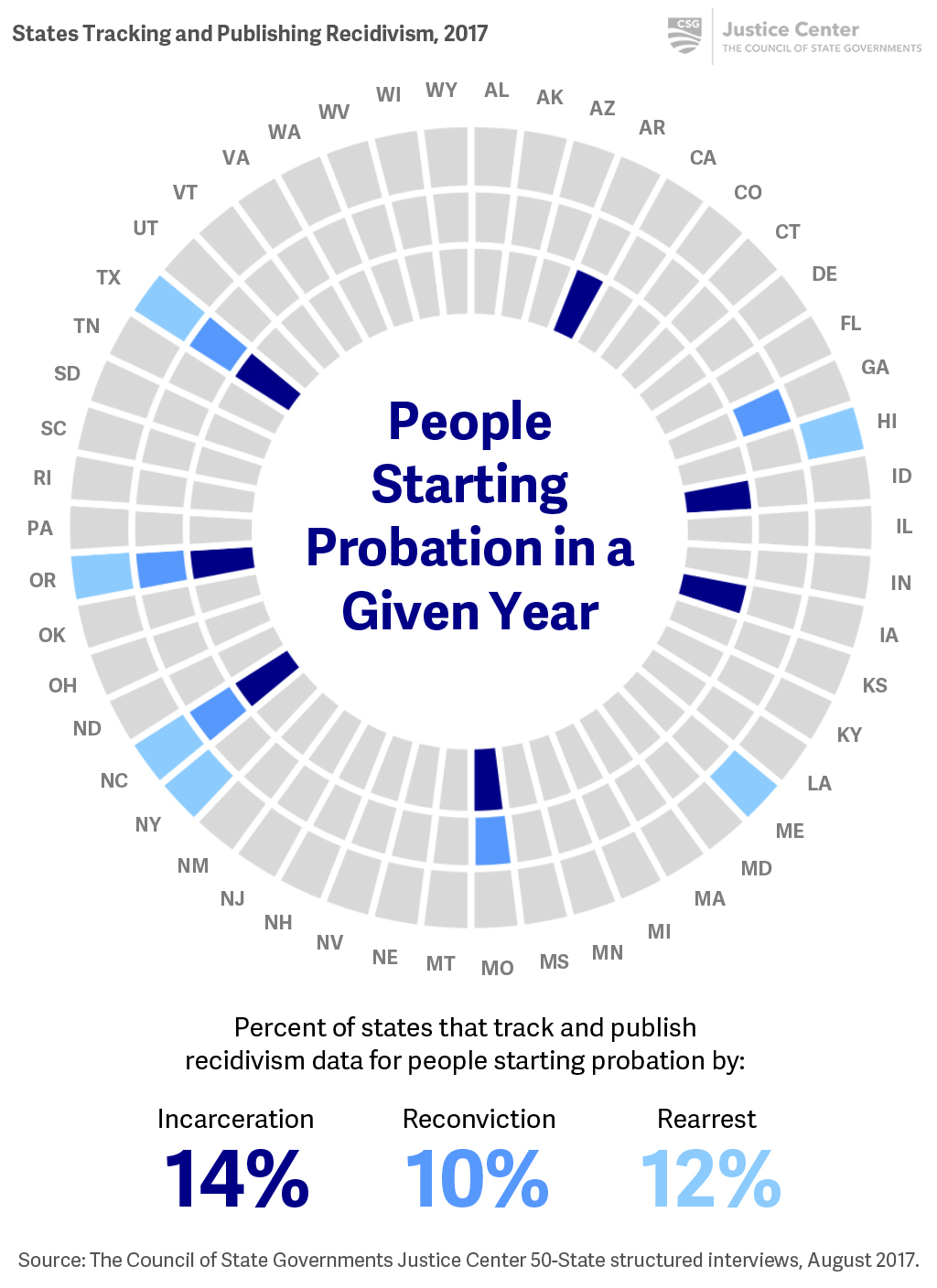

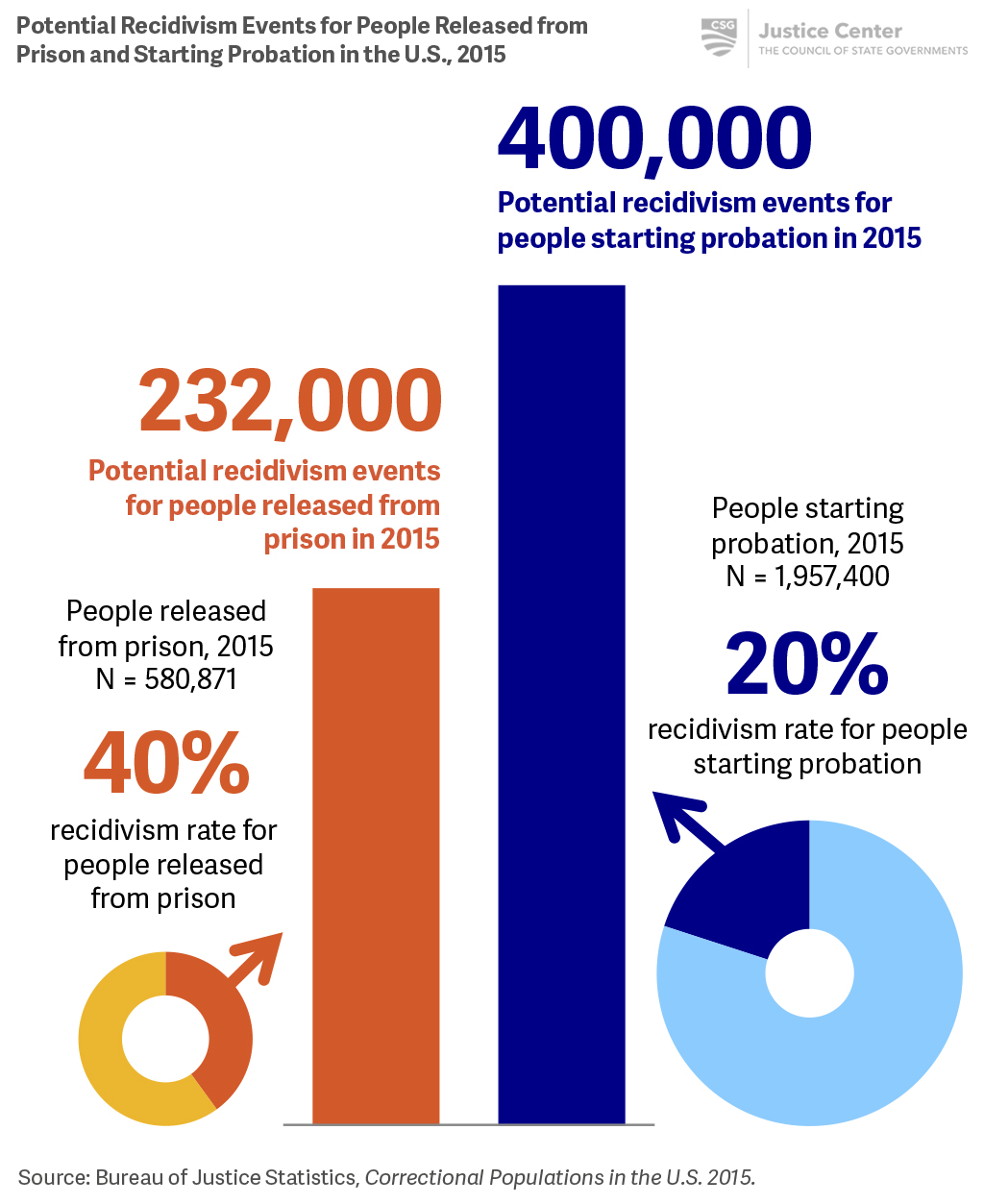

There are three times as many people starting probation as there are people leaving prison. Yet only 11 states track and publish at least one of the three recidivism measures for people starting probation, and only three states—North Carolina, Oregon, and Texas—publish all three measures for this population.[8] Despite having half the incarceration rates as people leaving prison, people on probation make up a much larger population and therefore can have a larger impact on crime, arrests, and prison admissions.[9]

Further, supervision agencies need to conduct the same types of analyses on recidivism for people starting probation, as those leaving prison. Supervision agencies need to analyze rearrest, reincarceration, and reconviction in multiple ways to understand what factors are driving trends so they can develop policies and practices to reduce recidivism among people on probation.

What it looks like

- Require probation agencies to track and publish incarceration, rearrest, and reconviction rates annually for all people starting probation.

- See Case Study: Strengthened probation practices in Arizona improve public safety and reduce spending

- Analyze and publish recidivism rates in multiple ways to identify factors driving reincarceration, rearrest, and reconviction trends and track changes in trends over time.

Key questions to guide action

- What additional measures does your state need to track and publish for people starting probation?

- What upgrades to data systems are necessary to report on all three measures of recidivism for people starting probation?

- If probation is county-run, how can your state support probation departments’ efforts to report on all three measures?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

Few states track and publish recidivism measures for the probation population.

Efforts to reduce recidivism for the probation population can have a greater impact than focusing only on people released from prison.

E. Ann Carson and Elizabeth Anderson, Prisoners in 2015; Danielle Kaeble and Thomas P. Bonczar, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2015. In 2015, 580,871 people left state prisons and 1,957,400 people began probation sentences. People can be sentenced to probation as an alternative to prison or as a mandatory period of supervision following incarceration. Probation agencies can operate at the state and local level.

Danielle Kaeble and Thomas P. Bonczar, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2015; Thomas H. Cohen and Tracey Kyckelhahn, Felony Defendants in Large Urban Counties, 2006 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010). Matthew R. Durose, Alexia D. Cooper, Ph.D., and Howard N. Snyder, PhD., Recidivism of Prisoners Release in 30 States in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010 (Washington, DC: Us. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2014). Most states administer probation for people convicted of felonies, but where probation is locally administered, states can require and support probation in reporting on recidivism figures.

Case Study

Strengthened probation practices in Arizona improve public safety and reduce spending

In 2008, people who violated the conditions of their probation accounted for one-third of all prison admissions in Arizona. As a result, the state spent an estimated $100 million to send more than 4,000 people to prison annually for failing on probation.

To improve public safety and save taxpayer dollars, Arizona sought to reduce the number of people revoked to prison for violating probation conditions and committing new crimes. In 2008, Arizona began an ongoing process to implement a series of changes to strengthen probation supervision. New laws also required the Supreme Court’s Administrative Office of the Courts to annually report to the legislature each probation agency’s progress toward meeting those goals.

- Policy changes included requiring judges to receive presentence reports that include criminogenic risk and needs assessment results, and updating supervision standards for determining how people of all risk levels are supervised.

- Training initiatives targeted toward probation officers, judges, and other criminal justice stakeholders included adopting evidence-based practices (EBPs), using presentence reports to inform supervision conditions, and focusing time and resources on people most likely to reoffend.

- Hiring practices were updated as Arizona moved from a compliance-oriented approach focused on monitoring and reacting to violations to incentivizing probationer accountability and behavior change. Modified hiring practices target recruits that fit this new paradigm of officer responsiveness. New recruits now receive training on EBPs at the academy, and all officers receive annual ongoing training.

These changes have collectively resulted in increased public safety and taxpayer savings. In FY2017, 31 percent fewer people entered prison in Arizona due to probation revocations than in FY2008.[10] Over the same period, the number of new felony convictions fell 17 percent.[11] These reductions saved Arizona taxpayers more than $461 million between FY2009 and FY2017.[12] For additional information, see Probation Performance: How Arizona’s County Probation Departments Increased Public Safety While Saving Taxpayers Millions.

[10] Kathy Waters, Jane Price, Dr. Maria Aguilar-Amaya, Safer Communities Report FY2017 (Phoenix, AZ: Arizona Supreme Court Adult Probation Services Division, 2017).

[11] Ibid.

[12] CSG Justice Center staff correspondence with Arizona Administrative Office of the Courts staff, March 15, 2018.