Part 2, Strategy 4

Action Item 4: Reduce barriers to housing.

Why it matters

Lack of stable housing complicates reentry for people leaving prisons or jails and can increase the risk of recidivism. Without a stable place to live, people leaving prison or jail have difficulty staying connected to mental health or substance addiction treatment or complying with terms of supervision. The lack of community-based housing options can also limit a parole board’s willingness to release people to parole supervision without a home plan, consequently keeping people incarcerated longer.

Research has also identified a subset of people who cycle repeatedly between homelessness and jails, and rely heavily on health services, resulting in high costs to local and state governments. For these people, supportive housing has been proven to be effective in helping reduce the risk of recidivism. People with less intensive needs may be connected to appropriate types and levels of housing assistance ranging from housing search services and tenancy supports to short- and long-term rental assistance to recovery and supportive housing.[52]

Helping people who are released from prisons or jails find safe places to live is critical to reducing homelessness and recidivism. Yet the obstacles to securing housing for people reentering the community are significant. As the cost of rental housing continues to rise relative to wages and incomes, private market rental housing, for instance, is not a viable option for many people exiting incarceration because of their low incomes, not to mention many landlords’ unwillingness to rent to people with criminal records. Many people leaving prisons or jails also have health and behavioral health challenges such as serious mental illnesses or substance addictions, and therefore may require supportive services in addition to help paying rent. The lack of viable housing options has led many people returning to communities from jail or prison to homelessness. Studies have shown that people are at a particularly high risk of becoming homeless and/or returning to the criminal justice system in the first month after release from prison or jail.[53] Homelessness and unstable housing, in turn, have been shown to increase the risk of recidivism.

Addressing the housing needs of people leaving prison or jail requires a multifaceted approach tailored to individuals’ particular housing and service needs. For some people, housing navigation and help with locating housing may be sufficient. Many people whose incomes are too low to afford private market housing could benefit from subsidized affordable housing or rental assistance programs such as the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher programs. Other people—including those who have behavioral health challenges—may need models like permanent supportive housing that integrate housing with supportive services.

Unfortunately, access to federal housing assistance programs, such as Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers or public housing, remain limited for people leaving prison or jail because many public housing authorities continue to deny assistance to applicants based on criminal histories. Federal homeless assistance programs—known as the Continuum of Care Program—may assist people who are cycling between homelessness and short-term jail stays, but are not viable for people who stay in jail or prison for 90 days or longer. Moreover, federal housing assistance programs in general are in scarce supply relative to demand.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has taken steps in recent years to make federal housing assistance programs more accessible to people with criminal records. HUD issued guidance in 2012 clarifying that public housing authorities may exercise flexibility in considering criminal history and are encouraged to have lenient criminal history review and screening policies.

What it looks like

- Limit the impact a criminal record has on obtaining housing.

- See Case Study: New York forbids housing discrimination based on a criminal conviction

- Enact laws reducing landlord liability.

- See Case Study: States limit liability for landlords

- Fund programs to provide housing stability for people who have behavioral health needs and/or criminal records.

- See Case Study: Jurisdictions implement supportive housing initiative

Key questions to guide action

- What steps might your state take to reduce the impact a criminal record has on a person’s ability to find housing, when appropriate?

- What laws does your state have to protect landlord liability when renting to people who have criminal records?

- Does your state provide funding for programs to provide housing for people who have criminal records and behavioral health needs?

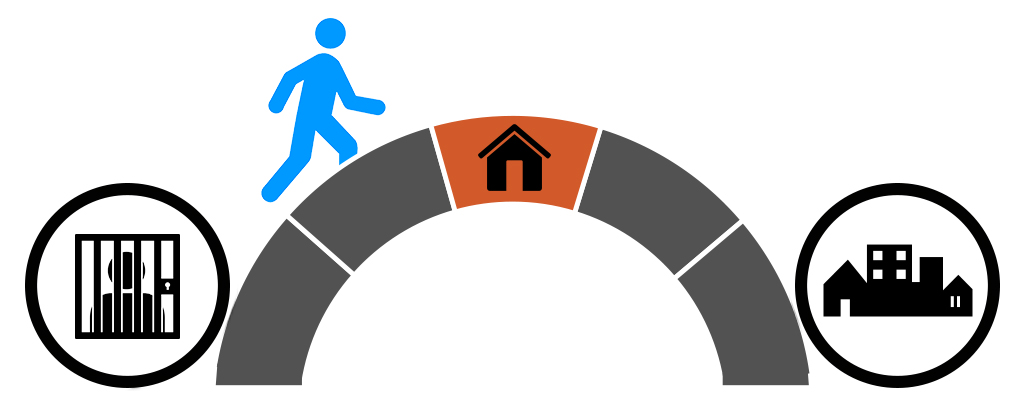

People leaving incarceration need a range of supports, including housing.

U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, “Connecting People Returning from Incarceration with Housing and Homeless Assistance,” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, 2016).

Council of State Governments, Report of the Re-Entry Policy Council (New York: Council of State Governments, 2005).

24 CFR § 982.553 (2010).

Case Study

New York forbids housing discrimination based on a criminal conviction

Some states are making state-financed vouchers and subsidies available to people who have criminal records and are encouraging landlords to make determinations regarding people who have criminal records on a case-by-case basis. For example, in New York, the governor issued guidance forbidding discrimination based on criminal conviction alone for Section 8 housing (using Housing Choice Vouchers), state-funded public housing, and other low-income housing. State-supported housing providers are required to make decisions based on an applicant’s individual history, such as the seriousness of the offense, how long ago it occurred, how old the applicant was at the time of the offense, and evidence of rehabilitation.[54]

[54] Legal Action Center, Helping Moms, Dads, and Kids to Come Home: Eliminating Barriers to Housing for People with Criminal Records (New York, NY: Legal Action Center, 2016).

Case Study

States limit liability for landlords

Enacting laws limiting landlord liability for housing people who have criminal convictions or providing funding to mitigate risks of renting encourages landlords to rent to people who have criminal records.

- North Carolina’s Certificate of Relief is granted to people with certain misdemeanor and low-level felony convictions. These certificates override most automatic disqualifications from housing and employment and serve as evidence of rehabilitation, while limiting civil actions against landlords who lease to people with Certificates of Relief.[55]

- Texas law provides landlords with limited protection against liability solely for renting or leasing to someone who has a criminal record.[56]

[55] Legal Aid of North Carolina, “Certificate of Relief from Collateral Consequences” (Raleigh, NC: Legal Aid of North Carolina).

[56] Section 92.025, Texas Property Code.

Case Study

Jurisdictions implement supportive housing initiative

Montana established a grant program to advance local efforts to remove barriers to housing for people returning to the community after incarceration. Grant funds may be used to provide case management and housing placement services, support landlord engagement activities, hire housing specialists, and build or manage risk-mitigation funds to reimburse landlords for tenant-related property damages or expenses. [57] In 2018, the state awarded grants totaling more than $390,000 to supportive housing programs in three municipalities. Each municipality has since hired program coordinators and housing specialists and conducted landlord and/or property manager outreach.

In 2013, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) launched the family reentry pilot program to reunite formerly incarcerated people with their families who live in NYCHA housing and connect them with reentry services to reduce their risk of reoffending and address their needs, including finding employment and/or continuing education and participating in substance addiction counseling. An evaluation found that the program had a positive impact on participants and their families and could serve as a model for similar programs nationwide. For additional information, see Coming Home: An Evaluation of the New York City Housing Authority’s Family Reentry Pilot Program.

Ohio’s Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections (DRC) offers permanent supportive housing for people in the criminal justice system and their families who experience chronic homelessness. People eligible for these services typically have some form of disability, mental health and/or substance addiction, or other medical problem for which the person receives ongoing treatment. Under this initiative, DRC pays for supportive housing where people also receive appropriate treatment and rehabilitative services. In FY2017, there were 196 permanent supportive housing beds statewide.[58]

[57] Montana Board of Crime Control, “Montana Board of Crime Control Request for Proposals (RFP) #18-07 (HG) Supportive Housing Grant,” (Helena, MT: Montana Board of Crime Control, 2018).

[58] Joseph Rogers, Greenbook, LSC Analysis of Enacted Budget, Department of Rehabilitation and Corrections Budget (Columbus, OH: Legislative Services Commission, 2017).