Part 1, Strategy 3

Action Item 1: Support collection and analysis of jail data.

Why it matters

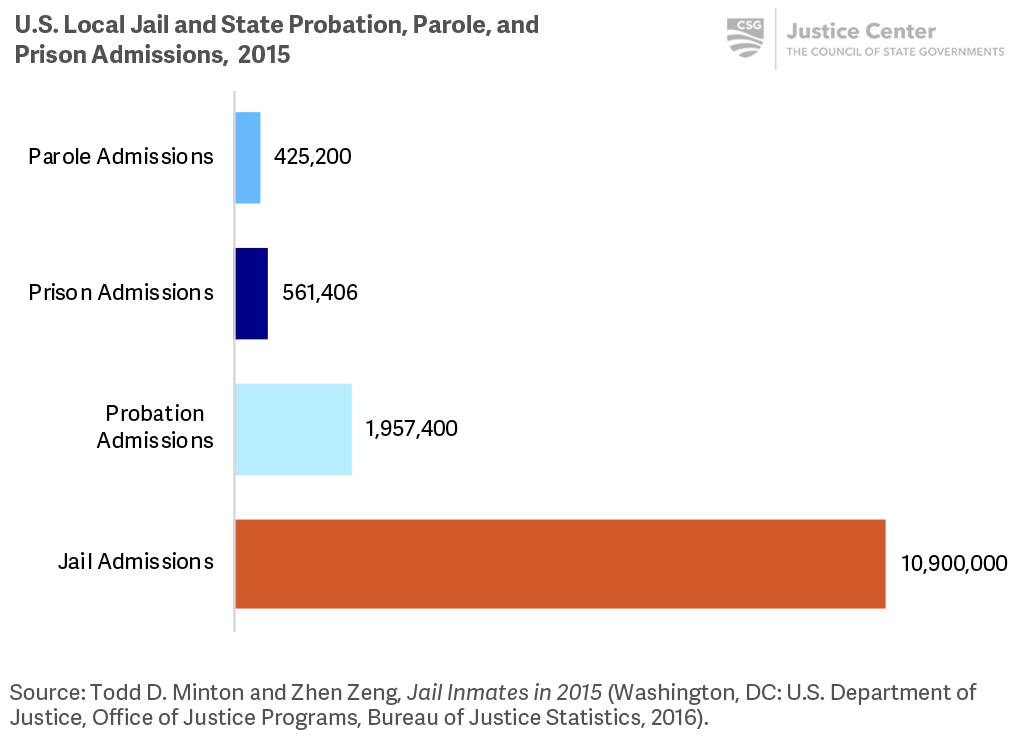

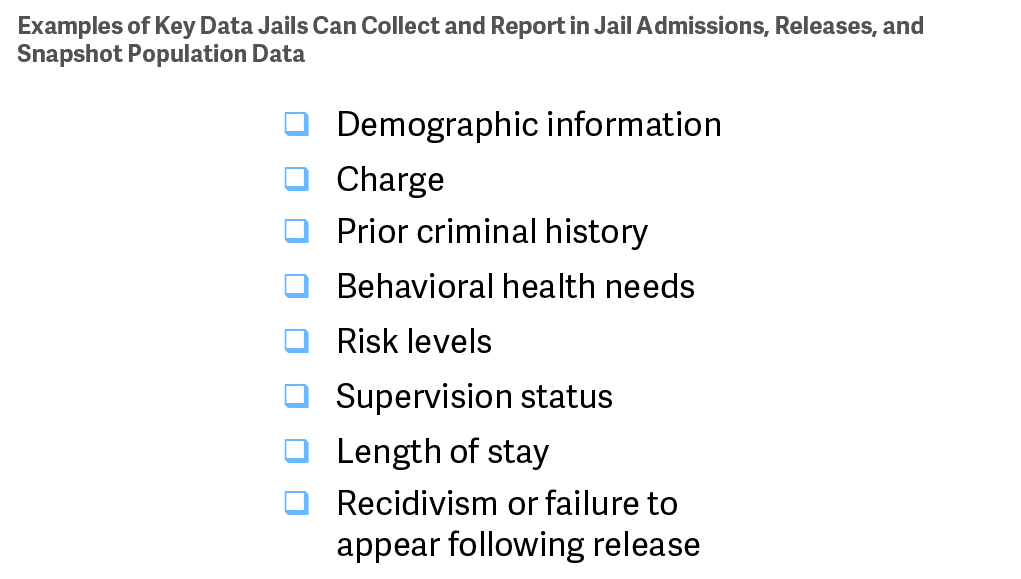

There are more than 3.5 times as many admissions to local jails each year as prison, probation, and parole admissions combined.[56] Each of the nation’s more than 3,000 jails need to collect a range of data showing who comes in, how long they stay, whether they have a mental illness or substance addiction, their supervision status, and whether they reoffend after release. This information can be used to measure how policies and practices are impacting public safety, hold agencies accountable for outcomes, and inform budgetary decisions. Good data can also help state leaders understand and potentially mitigate the impact state policy changes will have on local jails. States can help ensure consistency in collecting and reporting data by setting standards, providing financial support, data infrastructure, or other assistance to counties to improve data collection.

While law enforcement officers, jail administrators, and court officials across the country clamor for viable alternatives to incarceration for people who have behavioral health needs and are accused of relatively minor offenses, these officials do not know how many people entering their criminal justice system need treatment or are potential candidates for alternatives to incarceration. Currently, few jails routinely use and track the results from validated universal behavioral health and criminogenic screenings and assessments. Without this information, jails can’t identify the resources necessary to address behavioral health needs or successfully partner with other criminal justice and behavioral health agencies to advance recovery and reduce recidivism. (For more information on screening and assessment, see Part 1, Strategy 2.)

What it looks like

- Set statewide standards to improve consistency in jail data collection and reporting, including behavioral health data.

- See Case Study: Texas requires the identification of people who have mental health needs

- Use financial incentives to improve data collection and analysis.

- See Case Study: Florida sets standards for data collection and transparency

- Support collaboration among counties to collect and analyze data.

- See Case Study: Texas counties collaborate to improve data collection and sharing

- Assess the impact of state policies on jails and prisons.

- See Case Study: Washington State uses data to assess impact of policy changes on counties

- Track and publish pretrial performance measures, including failure to appear and rearrest rates by risk level.

- Support data sharing between criminal justice agencies.

Key questions to guide action

- How might your state help local jails improve data collection and reporting?

- What further information do state leaders need from jails to understand the impact of state policies?

- Are there any standards for reporting the number of people entering jails who have behavioral health needs?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

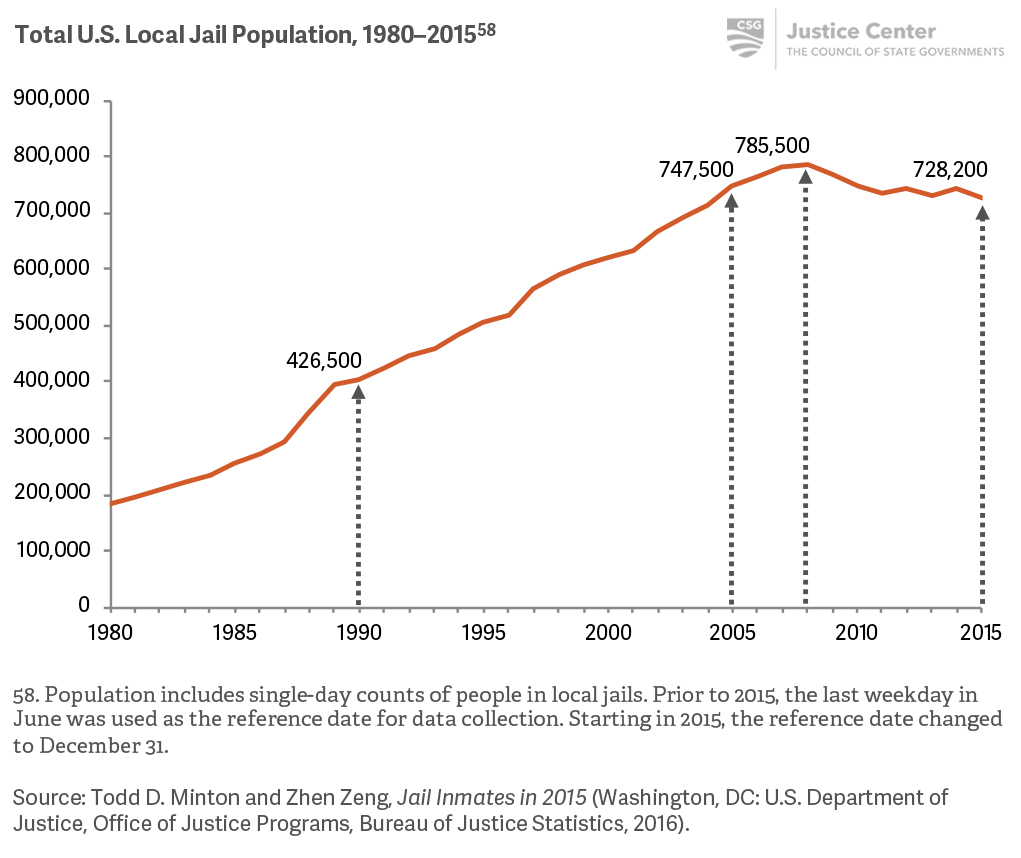

The local jail population has quadrupled since the 1980s, but has leveled off in the last 10 years.

Additional Resources

The Growth of Jail Populations in Rural America

Local trends can be more varied than a national snapshot suggests. Changes in a jail population could be triggered by growth or decline in the overall resident population or the number of young adults in the resident population; increases and decreases in crime; decisions by law enforcement and prosecutors about who to arrest, book into jail, or charge; local court policies and practices that affect how long people stay in jail pretrial and who gets released; and decisions to rent available jail space to other jurisdictions. State laws regarding permissible use of citations in lieu of arrests, responses to supervision violations, and statutory requirements of jail time for certain offenses can also impact population changes.

A recent report found that jail populations increased in rural areas over the past decade, while urban areas experienced significant declines. The report found that while overall rates of pretrial detention have risen nationally, the highest rates are most often in rural counties. Further, an increasing number of rural jails are renting out available jail beds to federal, state, or other local governments. For additional information on how rural jail populations have changed, see Out of Sight: The Growth of Rural Jails in America.

The number of people admitted to jail each year is far greater than the number of people admitted to prison or the number that start probation or parole supervision.

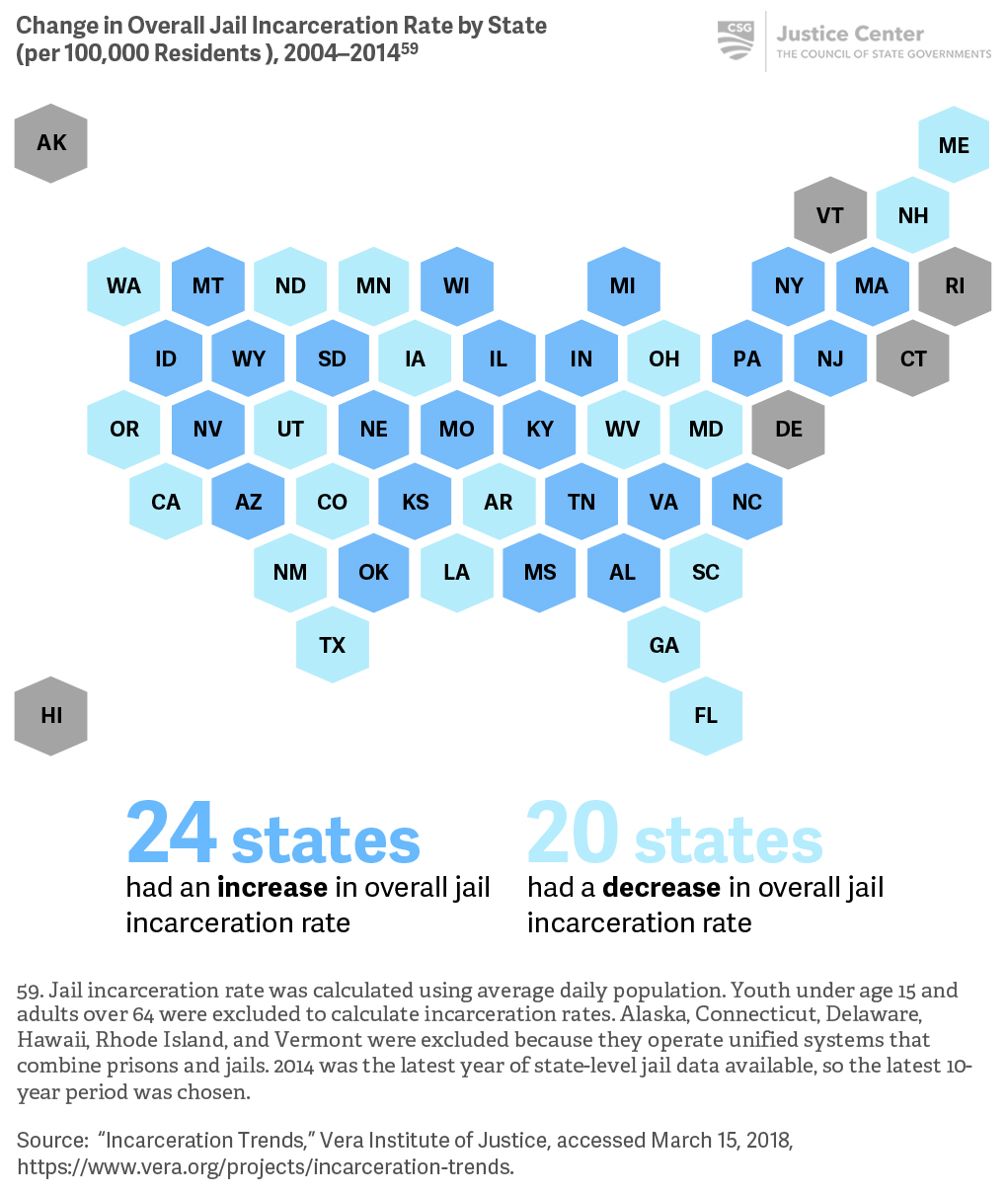

The overall jail incarceration rate has increased in 24 states and fallen in 20 states in recent years.

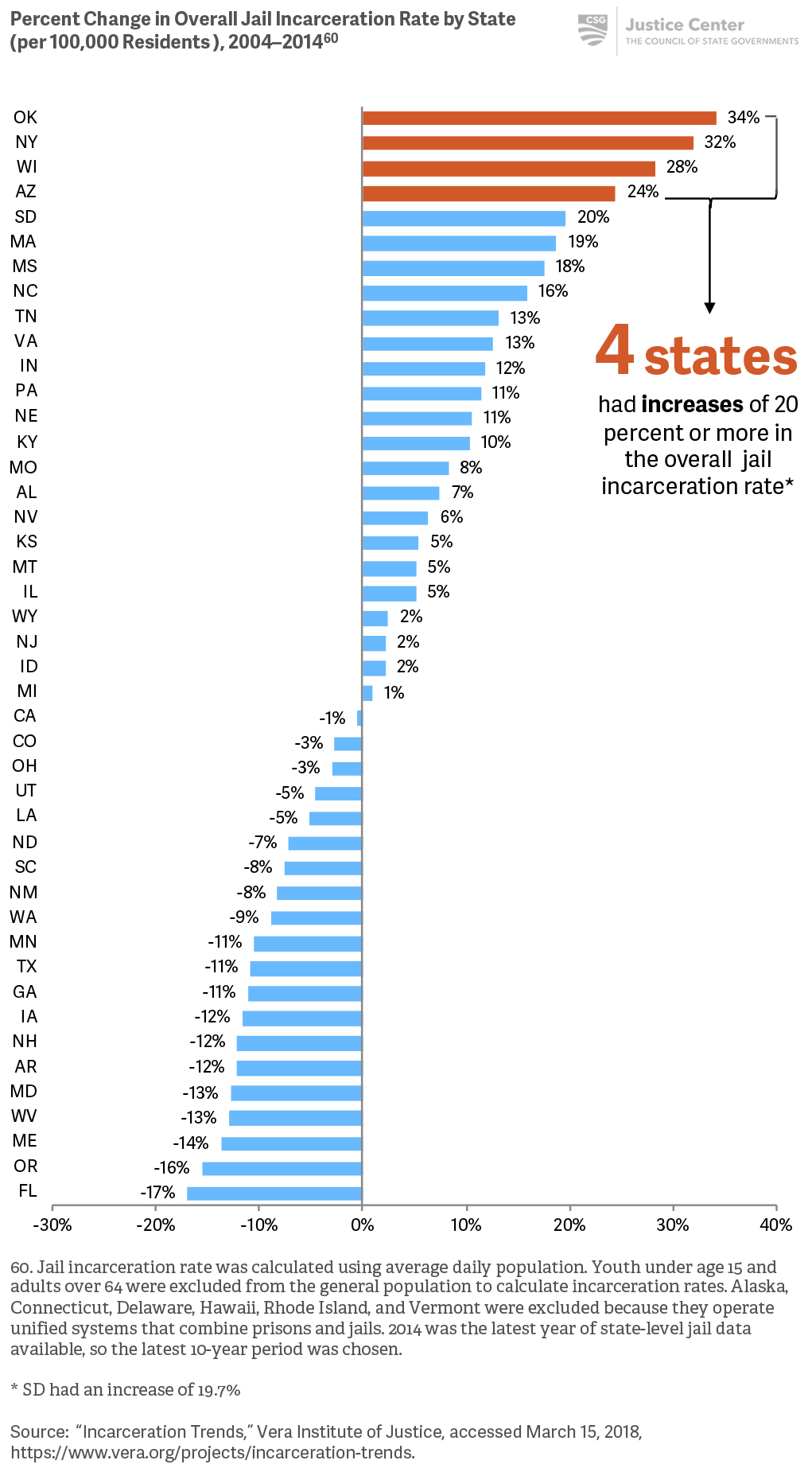

Changes in overall jail incarceration rates vary widely across states.

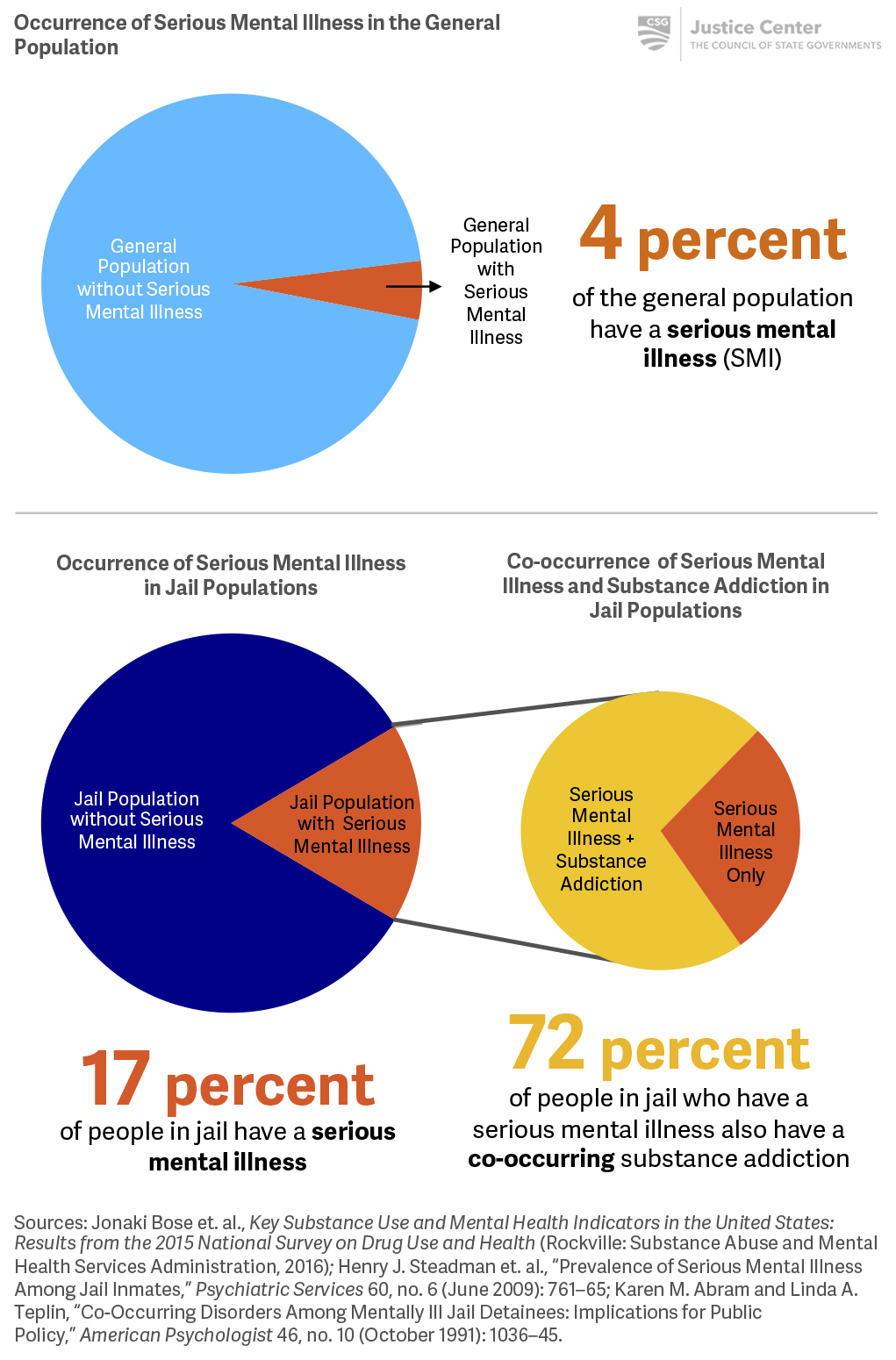

While the proportion of people in jail who have a serious mental illness is greater than for the general public, few jurisdictions know how many people in jail have behavioral health needs.

Additional Resources

Improving Pretrial Responses to People who have Mental Illnesses

Nationwide, approximately two million adults with serious mental illnesses are admitted to local jails each year, about three-quarters of whom have co-occurring substance addictions. In many communities, people who have mental illnesses are detained at higher rates and longer while awaiting trial than those who do not have mental illnesses. Improving Responses to People with Mental Illnesses at the Pretrial Stage can help policymakers understand the foundational principles for pretrial policy and the best practices for responding to people who have mental illnesses and co-occurring substance addictions.

Stepping Up

Since May 2015, 400 counties have passed resolutions to join Stepping Up, a national initiative to reduce the number of people in jails who have mental illnesses. Recognizing the critical role local and state officials play in supporting change, the National Association of Counties (NACo), The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center, and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation (APAF) are leading this unprecedented national initiative.

NACo, the CSG Justice Center, and APAF are working with partner organizations to build on the foundation of innovative and evidence-based practices already being implemented across the country, and to bring these efforts to scale. These partners have expertise in the complex issues addressed by Stepping Up and include sheriffs, jail administrators, judges, community corrections professionals and treatment providers, consumers, advocates, behavioral health directors, and other stakeholders.

Reducing the Number of People with Mental Illnesses in Jail: Six Questions County Leaders Need to Ask serves as a blueprint for counties to assess their existing efforts to reduce the number of people who have mental illnesses and co-occurring substance addictions in jail by considering specific questions and progress-tracking measures.

The six questions county leaders need to ask are:

- Is your leadership committed?

- Do you have timely screening and assessment?

- Do you have baseline data?

- Have you conducted a comprehensive process analysis and service inventory?

- Have you prioritized policy, practice, and funding?

- Do you track progress?

See Stepping Up for additional information.

Key data measures are essential to addressing the risk and needs of jail populations and ensuring that local governments use jail space cost-effectively.

Todd D. Minton and Zhen Zeng, Jail Inmates, 2015; E. Ann Carson and Elizabeth Anderson, Prisoners in 2012; Danielle Kaeble and Thomas P. Bonczar, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2015.

Case Study

Texas requires the identification of people who have mental health needs

By screening and assessing people for behavioral health needs, local jail administrators can identify people who have treatment needs, provide that information to the judge making the bail decision, and potentially connect the person to behavioral health care. (See Part 1, Strategy 2 for more information on screening and assessment.) States can support consistency in these efforts by providing guidance through statutes. For more than 30 years, Texas has refined a statutory framework to improve the identification of people who have mental illnesses entering jail.

History of Texas Policies on Identification of People Who Have Mental Illnesses Entering Jail

| 1983 | Created an interagency council, now known as the Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments (TCOOMMI), to coordinate diversion and treatment for juveniles and adults under supervision |

| 1993 | Required sheriffs to notify magistrate within 72 hours if a person has a mental illness |

| 1993 | Required magistrates to release defendants who have mental illnesses on personal bond (with exceptions for people who are charged with or who have previously been convicted of violent offenses) and to require treatment as a condition of release |

| 1995 | Allowed exchange of information between law enforcement and human services agencies to promote continuity of mental health care |

| 1997 | Allowed the magistrate not to order a mental health examination when there is a recent record of treatment as shown by a database match with the state mental health system |

| 2005 | Directed the Texas Commission on Jail Standards to require jails to use the state mental health system database to identify people who may have mental health needs |

| 2009 | Required the Texas Commission on Jail Standards to report to TCOOMMI on jails’ compliance with the 2005 mental health identification requirement |

| 2017 | Reduced the timing requirement for the mental health assessment to no longer than 72 hours for people in jail, and no longer than 30 days for people on pretrial supervision |

| 2017 | Mandated the use of a standard form to report assessment results for the transmission of information to magistrates |

Since the creation of the TCOOMMI, Texas lawmakers have consistently prioritized improving the identification of people with behavioral health needs in jails. Even with sustained state-level attention to this issue, implementation still presents challenges at the county level, including actually achieving early identification, access to clinicians for further assessment, judicial practices that limit referrals to treatment, and scarcity of treatment resources. For additional information, see: Playing the Long Game: Improving Criminal Justice in Texas.

Case Study

Florida sets standards for data collection and transparency

In 2018, Florida’s lawmakers passed landmark legislation making Florida the first state in the country to require all of its counties to collect data on more than 50 measures pertaining to the courts, jails, policing, and prisons in a statewide system that is accessible to the public.

Florida has 67 counties, each with its own criminal justice system made up of a diffuse network of law enforcement officers, jail administrators, and court officials. Ensuring that key details about each case pass from one agency to another within a single county is challenging and is nearly impossible at the state level. With such a disjointed system, common in many states, legislators realized they could not answer even the most basic questions such as, how many people are in jail? For what crimes? And for how long? Without this information, state leaders cannot measure how policies and practices are impacting public safety at the local level.

As a result, Florida’s lawmakers passed Senate Bill 1392, which increases data collection in the state by nearly 25 percent and targets several key measures that researchers were previously unable to analyze due to data limitations. Some of those measure include how bail is granted and on what terms; comprehensive race and ethnicity data, including accurate identification of Latinos; and details on the complete terms of plea offers.

As part of Senate Bill 1392, Florida’s lawmakers also

- Appropriated $1,750,000 for the development of a database that can connect disparate systems and present information in a user-friendly manner;

- Set statewide standards to improve consistency in data collection and reporting, especially among county jails;

- Established common definitions of terms in legislation to ensure that data across each county is comparable; and

- Issued financial incentives to ensure that every county participate.

For more information, see Florida Passes Historic Legislation to Help Close the Criminal Justice Data Gap.

Case Study

Texas counties collaborate to improve data collection and sharing

In Texas, counties collaborate on creating advanced technology by sharing the costs of research and development. Collaboration occurs through the Texas Conference of Urban Counties (CUC) which consists of 37 member counties and represents approximately 80 percent of the state population. CUC runs the TechShare program, through which counties develop technology that improves efficiency, productivity, document management, and ease of compliance with state regulations. While the TechShare program has produced case management systems for courts, prosecutors, and indigent defense programs, the TechShare.Juvenile system is the most extensively used.

Established in 2004, TechShare.Juvenile is a case management system for law enforcement agencies, school districts, courts, and supervision services working with youth. Having a single platform allows for information sharing as youth move between systems. Additionally, 250 of the 254 counties in Texas use TechShare.Juvenile data across the state, which results in a nearly complete set of statewide data.[57]

Any single county government would struggle to fund its own case management system. By banding together, counties in Texas advance their collective interest to fund and develop efficient case management systems.

[57] “TechShare Juvenile Program,” Texas Conference of Urban Counties, cuc.org/techsharejuvenile/.

Case Study

Washington State uses data to assess impact of policy changes on counties

When county-level data is available, counties and states can conduct analyses estimating the impact of proposed changes in state policies or practices. In 2014, Washington counties questioned whether proposed modifications to sentencing guidelines, which reduced certain sentence lengths but expanded the range of offenses that could lead to a jail sentence, could cause county jail populations to grow. The CSG Justice Center analyzed statewide data sets disaggregated by county to assess the potential impact of the sentencing changes on counties and found there would be no appreciable impact on any county in the state as a result of the proposed policies.