Part 1, Strategy 2

Action Item 2: Ensure that a range of behavioral health treatment and service options are available within jails and prisons and in the community for people in the criminal justice system.

Why it matters

The estimated proportion of people who have behavioral health needs is highest among people in jails compared to people in state prisons, on supervision, and in the general public.[36] Given the high volume of admissions to jails each year—more than 10.9 million in 2015 alone—diverting people who have behavioral health needs from jail to treatment and alternatives to incarceration, when appropriate, can have the biggest impact in reducing people’s involvement in the criminal justice system.[37] To effectively divert people from jail, jurisdictions need a range of behavioral health treatment and supports.

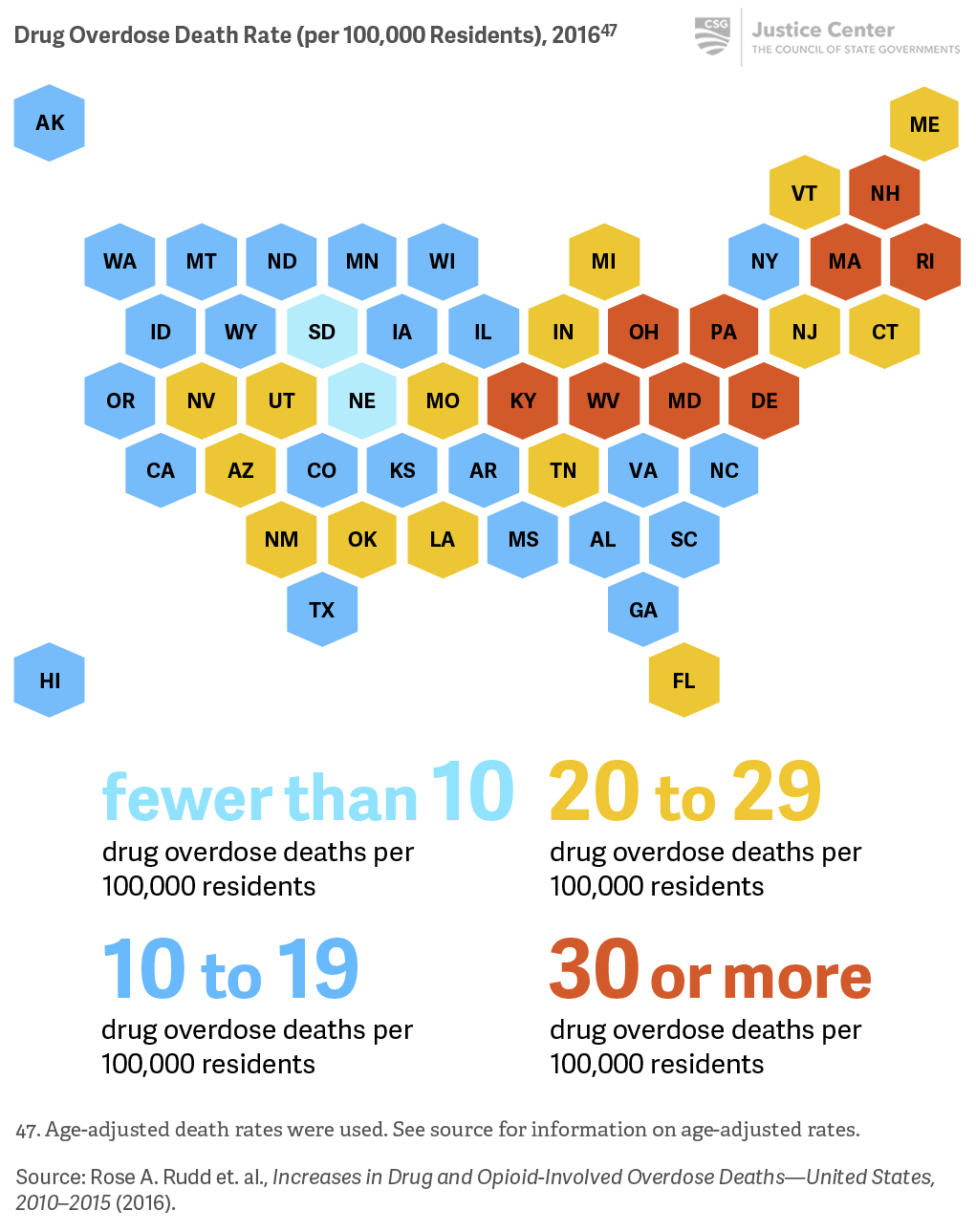

A disproportionate number of people in the criminal justice system need mental health and addiction treatment and supports compared to the general population. The U.S. Constitution establishes that people in jail and prison have the right to adequate health care, including behavioral health care, but providing this care can be challenging for a host of reasons, including difficulties in identifying who needs treatment and a lack of funding and capacity to provide the right amount and type of treatment.[38] Further, people on probation and parole supervision need access to treatment and services in the community. And, as the number of people overdosing on opioids reaches record levels, first responders and county and state leaders are seeking options to connect people to life-saving treatment and supports both in lieu of incarceration, when appropriate, but also during the period when people are at a high risk of overdose and death as they transition from incarceration back to their communities.

Because what each individual needs varies substantially, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to providing treatment and supports is not effective and can be a poor use of critical resources. Prioritizing resources for people who have the most serious behavioral health conditions and who are at the highest risk of reoffending and integrating services and supervision to address those risks and needs will deliver the best outcomes. (For additional information on effective supervision practices, see Part 2, Strategy 3.)

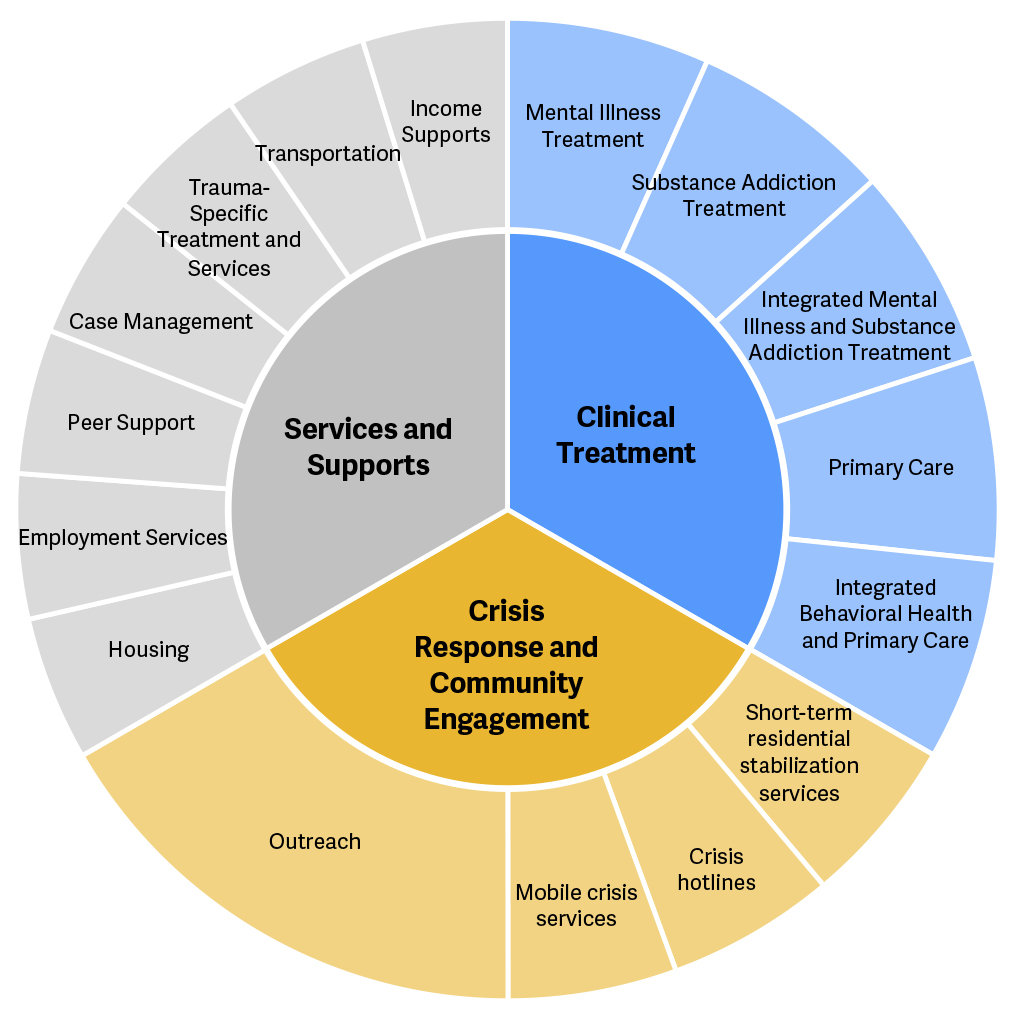

Carefully matching people to the appropriate level of care saves money and improves health and public safety outcomes. While some people in the criminal justice system need residential treatment, many more people can benefit from less intensive and less expensive outpatient or intensive outpatient community-based treatment. In addition to treatment provided by licensed professionals, people in the justice system may also benefit from services provided by paraprofessionals, such as peer-support specialists and recovery coaches, as well as assistance from case managers, health care “navigators,” and care coordinators.

People in the criminal justice system also have a range of needs beyond behavioral health and addiction treatment, including housing, transportation, or employment supports, as well as crisis-related services, such as crisis hotlines, mobile crisis services, and short-term residential stabilization services. The demand for each of these types of services typically far exceeds capacity. Overall outcomes are unlikely to improve if a system narrowly focuses on professional treatment services without consideration of these broader needs of people who have serious behavioral health conditions. (For additional information on housing and employment, see Part 2, Strategy 4.)

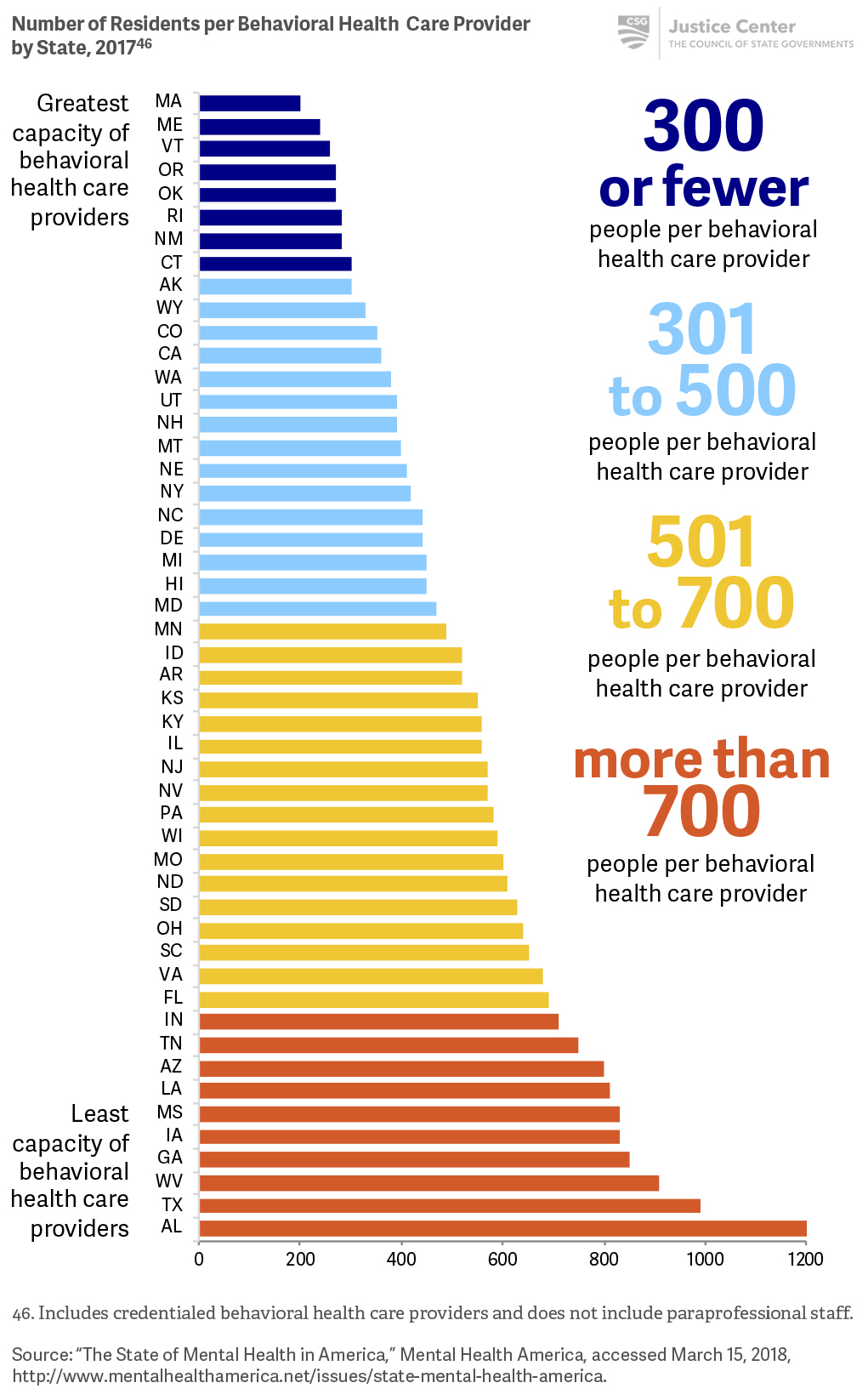

To provide a range of community-based treatment, services, and supports to people who have behavioral health needs in the criminal justice system, state and county leaders need to assess the range and capacity of resources available to this population to help policymakers make appropriate funding decisions to address gaps in services. An assessment of needs and available resources can also help policymakers develop strategies to enlarge capacity—such as expanding the use of telemedicine and ensuring adequate reimbursement rates for treatment providers—to increase the availability of treatment and services.

What it looks like

- Determine the number of people who have behavioral health needs and the specific nature of those needs.

- Help counties map existing opportunities for diversion and the availability of treatment and behavioral health services across the criminal justice system.

- Prioritize existing resources across the criminal justice and health care systems for people who are at a high risk of reoffending and have serious behavioral health needs.

- Support diverting people from jail to alternatives to incarceration and treatment, when appropriate, by statutorily defining categories permitting or excluding people from diversion.

- Fund local diversion programs and approaches that demonstrate alignment with locally identified needs, gaps, and circumstances.

- See Case Study: Jurisdictions establish crisis centers to reduce jail overcrowding and increase connections to treatment

- Provide funding and financial incentives to increase the availability of treatment and related services.

- See Case Study: North Dakota invests in treatment to improve the quality of services and expand the service provider workforce

- Develop a comprehensive approach to reduce drug overdoses through prevention, crisis response, treatment, and recovery support.

- See Case Study: Rhode Island develops approach to preventing drug overdoses

- Support efforts to redesign health care systems to expand capacity of community-based services that are responsive to the needs of people in the criminal justice system.

- See Case Study: Massachusetts launches pilot program to improve outcomes for people in the criminal justice system

Key questions to guide action

- What steps is your state taking to reduce the prevalence of people who have mental illnesses in jails?

- What is your state doing to reduce the number of overdose deaths for people who are at a high risk of overdosing in the period immediately after release from incarceration?

- Does your state evaluate the availability of treatment and services to determine necessary funding levels to meet the behavioral health needs of people in the criminal justice system?

- How can your state support local agencies in developing additional options to help reduce or avoid jail time, when appropriate, for people who have behavioral health conditions?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

Additional Resources

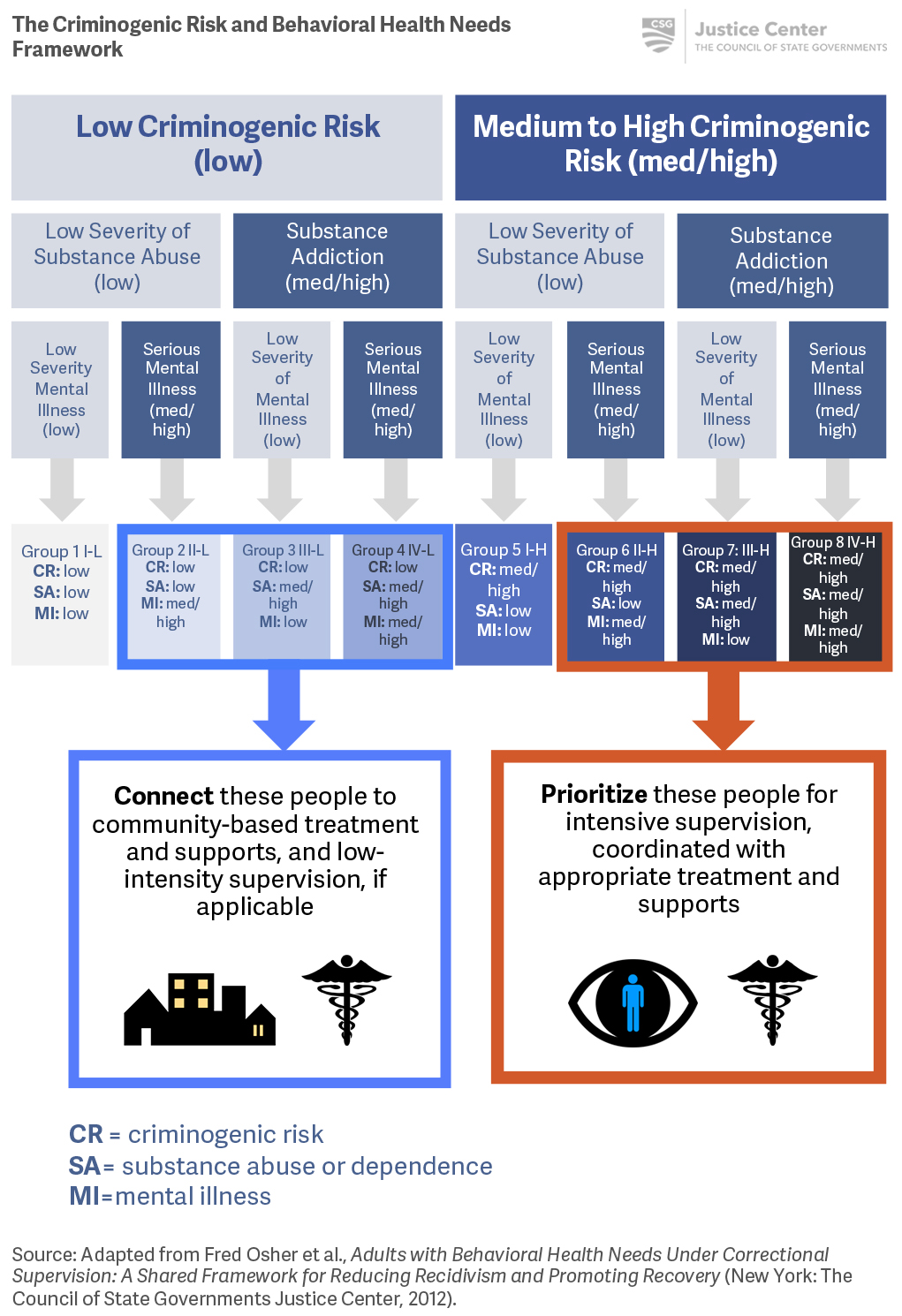

The Criminogenic Risk and Behavioral Health Needs Framework

Adults with Behavioral Health Needs Under Correctional Supervision: A Shared Framework for Reducing Recidivism and Promoting Recovery is a resource that outlines a structure for state and local behavioral health and criminal justice agency leaders to prioritize scarce resources for people based on their level of criminogenic risk and needs and the seriousness of their behavioral health conditions. Multi-agency collaboration across systems using the framework can facilitate coordinated responses that can have the greatest impacts on both recidivism and recovery. While the presence of a mental illness or substance addictions is not always an indicator of future criminal justice involvement, a comprehensive strategy to reduce recidivism for people who have mental illnesses and/or substance addictions must include the timely provision of appropriate levels of behavioral health care and services.45 The combination, duration, and intensity of supervision, supports, and services should be based on a comprehensive assessment of each individual’s behavioral health conditions and criminogenic risks and needs.

The Criminogenic Risk and Behavioral Health Needs Framework can help determine who to connect to treatment and supports, and who to prioritize for intensive treatment, supervision, and supports.

To implement the Criminogenic Risk and Behavioral Health Needs Framework, states and counties need a range of community-based treatment, services, and supports, and crisis response options and community engagement.

The capacity of behavioral health care providers varies from state to state.

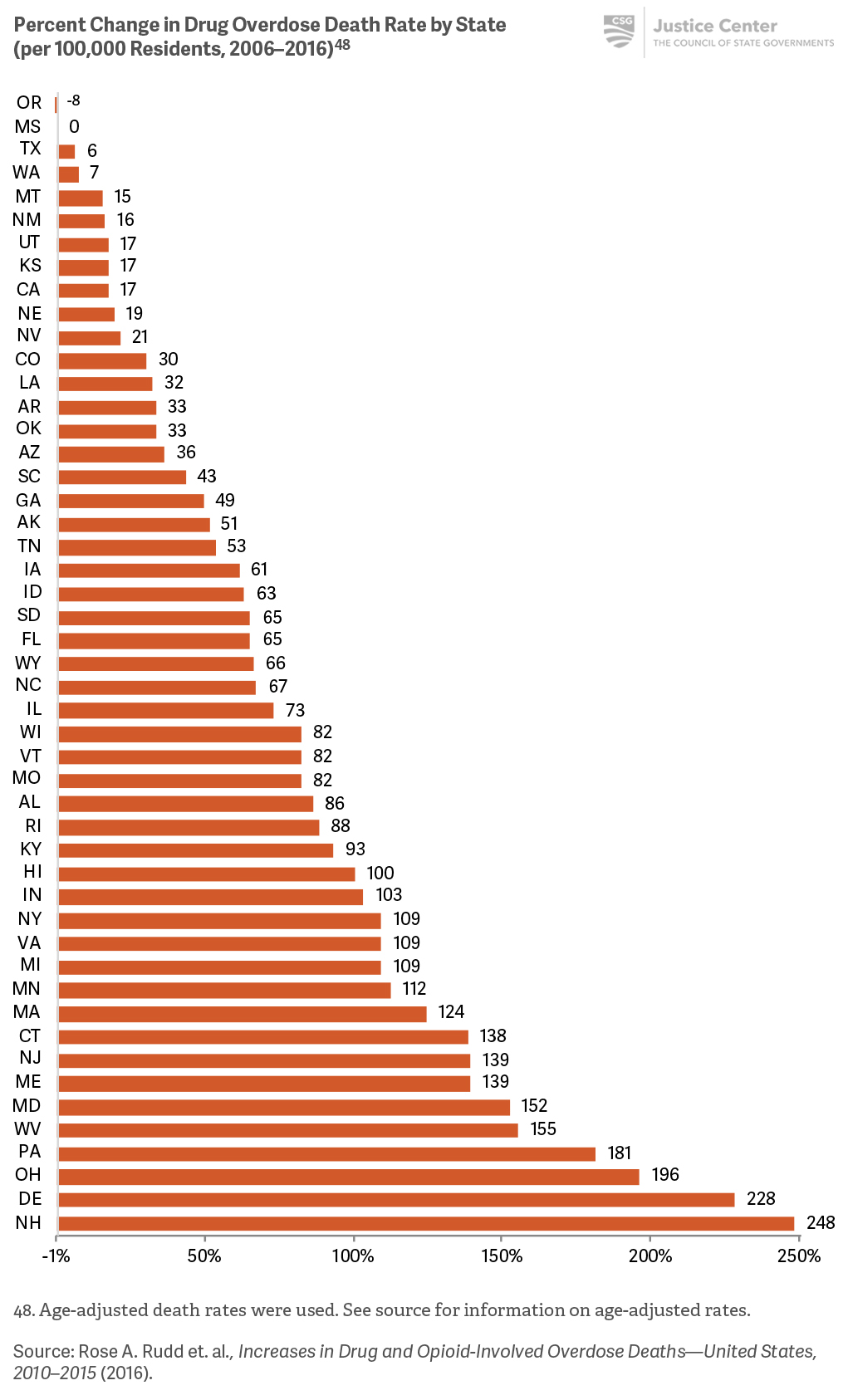

The nine states with the highest drug overdose death rates are primarily located in the Northeast.

Nearly every state had an increase in overdose death rates of more than 5 percent between 2006 and 2016. In 16 states, overdose death rates more than doubled during this period.

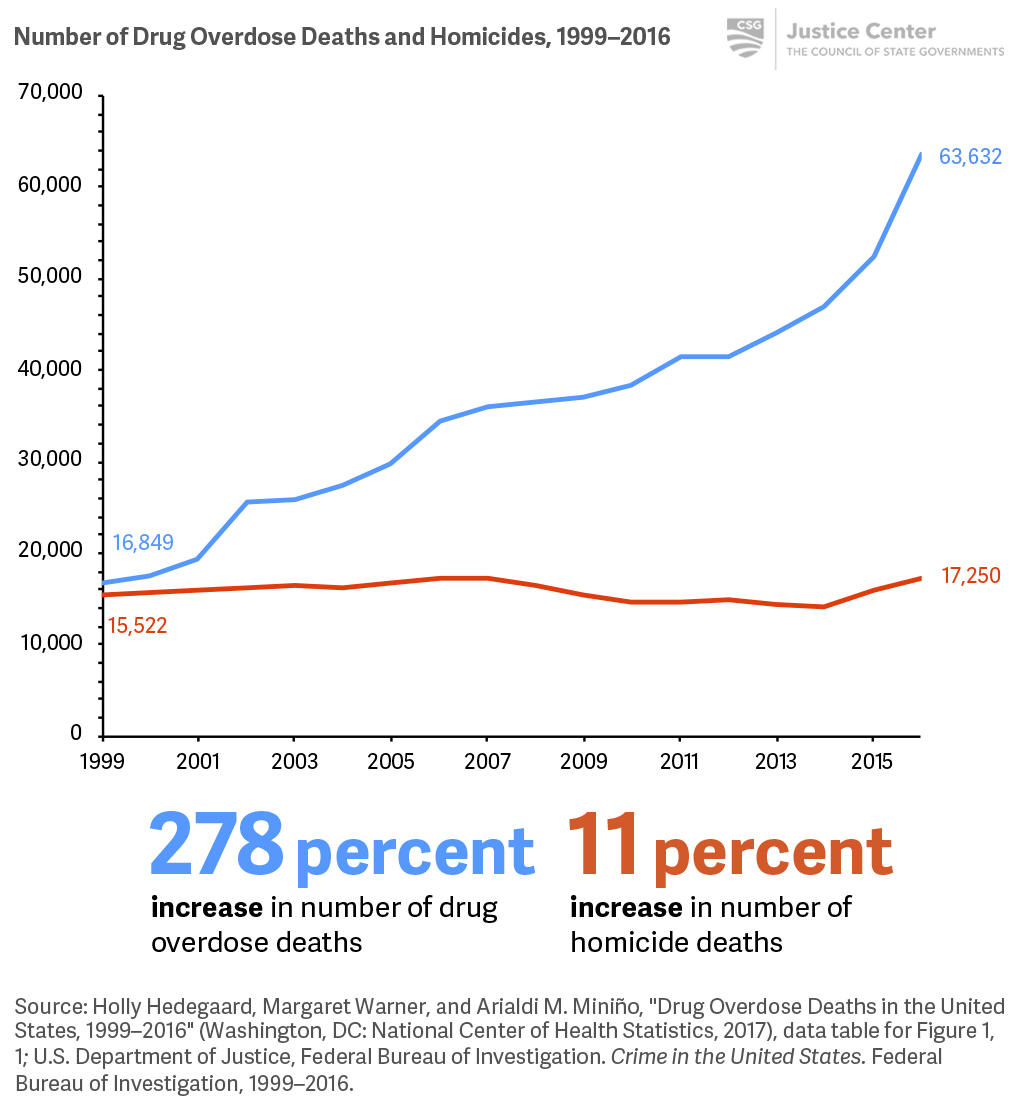

The number of drug overdose deaths used to mirror the number of homicides, but is now almost four times higher.

Todd D. Minton and Zhen Zeng, Jail Inmates, 2015 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2016); E. Ann Carson and Elizabeth Anderson, Prisoners in 2015 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, December 2016); Danielle Kaeble and Thomas P. Bonczar, Probation and Parole in the United States, 2015 (Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, December 2016); Blandford and Osher, Guidelines for the Successful Transition of People with Behavioral Health Disorders from Jail and Prison; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Todd D. Minton and Zhen Zeng, Jail Inmates, 2015.

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97, 103 (1976). The Eighth Amendment protects incarcerated people from “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Richard A. Van Dorn et al., “Effects of Outpatient Treatment on Risk of Arrest of Adults with Serious Mental Illness and Associated Costs,” Psychiatric Services 64, no. 9 (2013): 856–862; Faye S. Taxman, “Reducing Recidivism through a Seamless System of Care,” (paper, Office of National Drug Control Policy Treatment and Criminal Justice System Conference, February 20, 1998); Lois A. Ventura et al., “Case Management and Recidivism of Mentally Ill Persons Released From Jail,” Psychiatric Services 49, no. 10 (1998): 1330–1337.

Behavioral health diversion specifically refers to interventions that are designed to identify people in the criminal justice system who have behavioral health needs and, when appropriate, reroute them from institutional settings to receive community-based treatment services and supports. Not every person who has a behavioral health need and is involved in the justice system should be diverted; diversion may not be the most appropriate option, depending on the circumstances.

For the purposes of this report, references to diversion relate to adult jail diversion, meaning that a person who has a behavioral health need who is eligible to be diverted to treatment may still have contact with the criminal justice system (such as the courts) but spends little to no time in a jail facility.

Case Study

Jurisdictions establish crisis centers to reduce jail overcrowding and increase connections to community-based treatment

Across the country, counties and states are establishing crisis stabilization centers to receive people experiencing mental health crises as an alternative to sending them to jail. One of the nation’s longest-running county-funded crisis centers is in Bexar County, Texas. In 2003, Bexar County established a jail diversion program to connect people who have mental health and substance addictions to services instead of arresting and jailing them, when appropriate. As part of this program, the county not only established a crisis center to receive people in need of immediate assistance, but also trained law enforcement and other first responders in crisis intervention, and invested in community-based behavioral health treatment and services.

Local officials report that between 2003 and 2015, more than 20,000 people had been diverted from jail to treatment, saving taxpayers an estimated $50 million dollars and helping to reduce the county jail population.[39]

Based on these successes, other jurisdictions, including the states of Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Tennessee have followed Bexar County’s example and established similar capacity for diversion from involvement in the criminal justice system.

[39] Susan Pamerleau, “Jail Diversion Program a Huge Success,” My San Antonio, January 22, 2016; Kate Murphy and Christi Barr, Overincarceration of People with Mental Illness: Pretrial Diversion Across the Country and the Next Steps for Texas to Improve its Efforts and Increase Utilization (Austin, TX: Texas Public Policy Foundation, 2015).

Case Study

North Dakota invests in treatment to improve the quality of services and expand the service provider workforce

In North Dakota, people on community supervision—especially those who live in rural areas—have difficulty accessing behavioral health treatment due to insufficient service capacity. In 2016, 70 percent of judges reported sometimes sentencing people to prison in order to connect them with the behavioral health treatment they need.[40] In that same year, probation and parole officers reported that 75 percent or more of the people they supervised needed substance addiction treatment but struggled to find appropriate services in the community.[41] As a result, people who had behavioral health needs often ended up in jail or prison, leading the state to have some of the fastest-growing jail and prison populations in the country. Insufficient community-based treatment resources greatly limited the state’s ability to address treatment needs, improve health outcomes, and reduce recidivism, and, therefore, posed a challenge to public safety. To address these challenges, North Dakota invested $7.5 million in a two-pronged approach for providing community treatment for people who have behavioral health needs.[42]

Improve Quality of Services

In 2017, state policymakers created a community-based behavioral health program as a collaboration between the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (DOCR) and the Department of Human Services (DHS). Named “Free through Recovery,” the purpose of this new program is to increase access to services for people in the criminal justice system who have serious behavioral health conditions and are at a high risk of reoffending. The program began providing services statewide in February 2018, including in traditionally underserved rural areas. At a minimum, each program participant is assigned a care coordinator and a peer support specialist to work with the person to achieve recovery. The care coordinator helps participants access treatment and recovery support services and creatively address barriers to individual success. The peer support specialist is a person with lived experience who has behavioral health challenges in stable long-term recovery who has received training to support people as part of a multidisciplinary team. To encourage the improvement of key public safety and public health outcomes, service providers have an opportunity to earn additional performance-based compensation for meeting or exceeding specific outcome measures.

Expand Provider Workforce

As an immediate measure, the state created training and certification processes for peer support specialists, and additional training for care coordinators who will play important roles in the Free through Recovery program by connecting people to treatment, housing, and employment resources and coordinating multi-agency, multi-disciplinary collaborative teams.

North Dakota also required the development of a statewide strategic plan to meet its long-term goal of increasing the number of community-based behavioral health care providers across all regions of the state who are able to work effectively with criminal justice populations.

Strategies may include: conducting outreach to promote interest in behavioral health professions in rural areas; developing scholarships and loan forgiveness programs; creating distance learning opportunities; and bolstering out-of-state recruitment and retention.

[40] CSG Justice Center electronic survey of North Dakota judges, 2016.

[41] CSG Justice Center electronic survey of North Dakota probation and parole officers, 2016.

[42] “North Dakota Allocates $7M for Addiction Treatment and Passes Bills to Help Reduce Prison Population Growth,” CSG Justice Center, updated April 24, 2017, https://csgjusticecenter.org/jr/north-dakota/posts/north-dakota-allocates-7m-for-addiction-treatment-and-passes-bills-to-help-reduce-prison-population-growth/.

Case Study

Rhode Island develops approach to preventing drug overdoses

In 2015, Rhode Island Governor Gina Raimondo established the Governor’s Overdose Prevention and Intervention Task Force. In combination with the Rhode Island Department of Health, the Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals, and the Brown University School of Public Health, the task force developed a comprehensive strategic plan to reduce overdose deaths by one-third by 2018 by relying on a four-pronged strategy of prevention, rescue, treatment, and recovery.

The action plan developed by the task force sought to develop a network of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) opportunities so that people who have opioid addictions have many chances to receive MAT.

Accordingly, the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (RIDOC) began screening people for opioid dependency upon admission to jail or prison facilities. RIDOC also increased offerings of MAT, such as methadone, during incarceration and increased the use of MAT prior to a person’s release along with an accompanying referral for ongoing treatment assistance in the community.

In addition to comprehensive strategies to support prevention, rescue, treatment, and recovery, the task force action plan also established publicly available metrics and data tracking to measure the impact of these strategies.

To learn more, see Prevent Overdose RI.

Case Study

Massachusetts launches pilot program to improve outcomes for people in the criminal justice system

As part of its 2017 Justice Reinvestment project, the Massachusetts legislature allocated $1 million in 2018 to the Executive Office of Health and Human Services for the development of a pilot behavioral health program with the goal of improving outcomes for people in the criminal justice system who have serious behavioral health conditions. Although Massachusetts is a Medicaid expansion state with one of the highest rates of post-incarceration health care enrollment and the highest ratio of behavioral health providers for its population in the country, stakeholders repeatedly reported an inability to connect people on probation or recently released from incarceration to timely and effective behavioral health care services as one of their top concerns.[43] These gaps in services and the difficulty in connecting people to the right services contributed to high recidivism; between 2011 and 2014, two-thirds of people leaving Massachusetts Houses of Corrections (HOCs) and more than half of those leaving Department of Correction (DOC) facilities were rearraigned within three years of release.[44]

The Massachusetts pilot program uses an approach called “reach-in reentry.” People who have serious mental illnesses and substance addictions are identified during incarceration and provided with “in reach” from a community-based care provider to develop post-release treatment plans, make appointments with community-based health care providers, assist with obtaining housing and other services, and establish a community support network when possible prior to release. When appropriate, medication-assisted treatment can be initiated while a person is still incarcerated, and the community-based health care provider can foster health information sharing to facilitate ongoing treatment following the person’s release.

After someone is released, community-based providers offer intensive care coordination and daily contact during the first month, with ongoing contact as needed after that period. During the first month, a comprehensive care plan is developed and the coordinator provides assistance with making and keeping appointments, accessing medications, as well as obtaining and maintaining housing and social services as needed.

[43] Martha R. Plotkin and Alex M. Blandford, Critical Connections: Getting People Leaving Prison and Jail the Mental Health Care and Substance Use Treatment They Need (New York: Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2017); CSG Justice Center, Justice Reinvestment in Massachusetts Policy Framework (New York: CSG Justice Center, February 2017).

[44] HOCs are operated by independently elected county sheriffs. These facilities house people convicted of a misdemeanor or felony who have been sentenced to a period of confinement for no more than 30 months. DOC facilities are operated by the state and primarily house people who have been convicted of a felony and sentenced to a period of confinement at DOC for at least one year. CSG Justice Center analysis of FY2011–2014 Parole Board’s State Parole Integrated Records and Information Tracking System (SPIRIT) HOC data, as well as DOC and Department of Criminal Justice Information Services (CORI) data.