Part 3, Strategy 1

Action Item 2: Analyze prison and supervision population trends to understand how they are driving costs.

Why it matters

Understanding how and why the size of a state’s prison and supervision populations has changed over time can help state leaders better plan for the future. For example, changes in prison and supervision populations should trigger additional questions about what is driving those changes, how they correspond to crime and arrest trends, and how policy may be causing increases or decreases in those populations.

Additionally, a better understanding of changes in prison and supervision population trends can provide insight into associated cost trends. Most often, growing populations lead to growing costs for corrections systems, though this is not always the case.[6] States should carefully review the relationship between changes in population and costs to determine the best opportunities to maximize the use of public safety resources.

What it looks like

- Require corrections and supervision agencies to track and publish data on current and past population counts.

- Analyze data to understand the drivers of any changes in the size and/or composition of prison and supervision populations.

- Develop and implement policies to address growing corrections costs and/or populations.

- See Case Study: Missouri develops policies to address drivers of prison population growth

- See Case Study: Rhode Island changes supervision policy to reduce prison admissions

Key questions to guide action

- How did the size of your correctional populations change over the past decade?

- What are the largest contributors to changes in prison, parole, and probation populations in your state?

- What data collection improvements can be made to increase understanding of the factors that impact the size of your state’s correctional populations?

Use the information that follows to inform your answers to these questions.

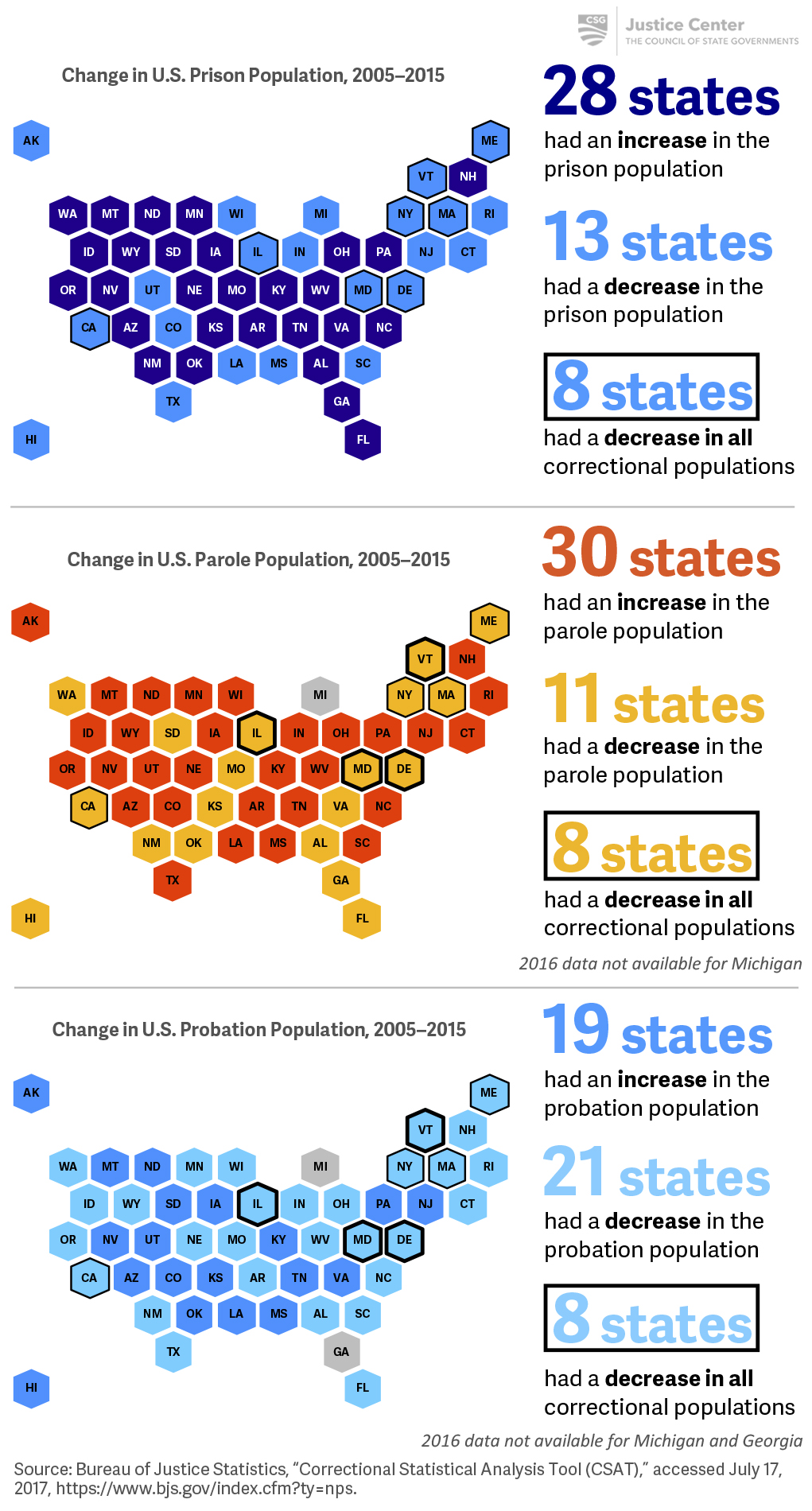

All but eight states saw an increase in correctional populations in the last decade.

Chris Mai and Ram Subramanian, The Price of Prisons: Examining State Spending Trends, 2010–2015, (New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice, 2017).

Case Study

Missouri develops policies to address drivers of prison population growth

Missouri is confronting a number of troubling trends in its criminal justice system, including a fast-growing female prison population. To address these challenges, Missouri initiated a Justice Reinvestment approach in 2017.

Data analysis during the Justice Reinvestment process revealed divergent trends between women and men in the Missouri criminal justice system:

- Between 2006 and 2016, arrests for drug offenses increased 31 percent for women, while arrests for drug offenses decreased 11 percent for men. During that period, arrests for property offenses increased 1 percent for women and decreased 22 percent for men.[7]

- In FY2016, nearly half of all women admitted to prison for new offenses in Missouri were admitted for drug offenses, compared to less than one-third of men admitted to prison for new offenses.[8]

- The number of women admitted to prison for behavioral health treatment increased 17 times faster than the number of men from FY2007 to FY2016.[9]

- Nearly two-thirds of women admitted to prison for supervision violations in FY2016 were admitted for technical violations, compared to just over half of men who were admitted for the same reason.[10]

- Between FY2007 and FY2016, the number of women revoked from supervision increased 29 percent and the number of men decreased 7 percent.[11]

Breaking down prison and supervision population statistics by gender not only helps policymakers plan for housing women in prison, but also provides valuable insight into how to address women’s needs. Accordingly, Missouri enacted legislation that responds to these trends:

- Implement treatment and programming models that account for gender-specific needs, the effects of trauma, and behavioral health challenges in criminal justice populations.

- Help women succeed on supervision by establishing more community-based behavioral health treatment and programming and relying less on prison-based treatment, which has been shown to be less effective. [12]

- Establish a female-only community supervision center to serve as a gender-responsive, trauma-informed center of services for women on community supervision.

[7] Andy Barbee et al., “Justice Reinvestment in Missouri: Third Presentation to the Missouri State Justice Reinvestment Task Force,” (PowerPoint presentation, Justice Reinvestment Task Force, Jefferson City, MO, October 24, 2017). Property offenses include burglary, larceny, motor vehicle theft, arson, forgery, fraud, embezzlement, and possessing stolen property.

[8] Andy Barbee et al., “Justice Reinvestment in Missouri: Third Presentation to the Missouri State Justice Reinvestment Task Force.” About half of all new admissions to prison were for long-term treatment and were not the result of a new court sentence.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] CSG analysis of Missouri Department of Corrections supervision data, September 2017.

[12]Andy Barbee et al., “Justice Reinvestment in Missouri: Fourth Presentation to the Missouri State Justice Reinvestment Task Force,” (PowerPoint presentation, Justice Reinvestment Task Force, Jefferson City, MO, November 28, 2017).

Case Study

Rhode Island changes supervision policy to reduce prison admissions

In 2015, the Rhode Island Department of Corrections (RIDOC) projected that after years of steady decline, the state’s incarcerated population would grow 11 percent by FY2025, at an estimated cost to the state of $28 million in additional operating and staffing costs.

JRI analysis revealed that the state’s outdated probation system significantly contributed to the number of people incarcerated. In FY2015, one-fourth of pretrial admissions to the state’s Adult Correctional Institutions were for alleged violations of probation conditions, and an estimated 60 percent of sentenced admissions were for probation violations. Due to the exceptionally large number of people on probation and the lengthy terms they were serving, probation officers were unable to provide meaningful supervision that reduces recidivism and improves public safety.

To modernize sentencing and probation supervision policies, Rhode Island passed and adopted a budget in 2016 that included an upfront investment of $893,000 earmarked for implementation of JRI efforts in the state. This investment allowed RIDOC to: (1) hire and train additional probation officers, (2) develop a three-year strategic plan for improving supervision practices and for sustaining adherence to evidence-based principles, (3) enhance practices for conducting risk assessments, and (4) develop contracts for community-based cognitive behavioral interventions.

The Rhode Island Supreme Court also adopted a series of amendments to the Superior Court Rules of Criminal Procedure and Superior Court Sentencing Benchmarks to address the standard of proof for probation violations, create a mechanism for probation termination, and set a benchmark for sentencing people convicted of nonviolent felony offenses to probation.

In 2017, legislation passed with bipartisan support in both the Senate and the House and was signed by Governor Gina Raimondo on October 5, 2017. The legislation aims to

- Align probation and parole policies with evidence-based practices;

- Focus probation supervision resources on high-risk, high-needs people and expand community-based programs to reduce recidivism;

- Assess defendants to inform diversion opportunities and pretrial supervision conditions; and

- Improve services to victims throughout the criminal justice system.

For additional information, see Justice Reinvestment in Rhode Island.